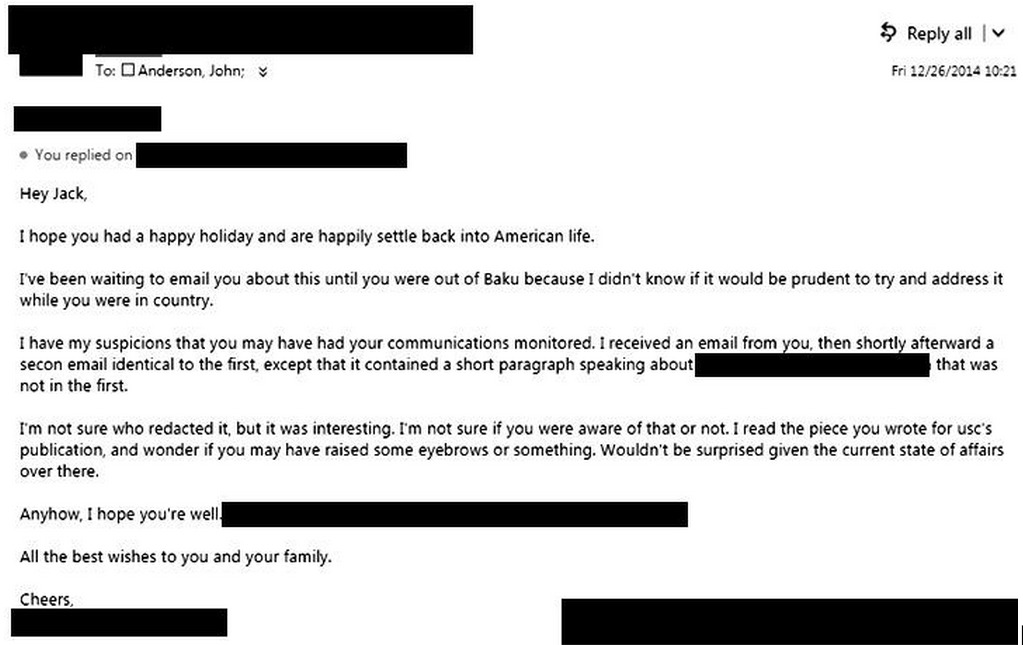

I received the email pictured above from a friend last year shortly after returning to the United States from Azerbaijan. He was alleging that my email account had been hacked into, and that the perpetrators were editing my emails before they could arrive at their intended destinations. Above is his reply, in which he explains his suspicions about the incident; I have blacked out sections of it to protect his identity. I have been unable to verify who hacked into my account and scrubbed a few sentences of the email. Given the Azerbaijani government’s distaste for independent journalists, I could think of a couple good reasons why my account may have been monitored: two articles I had written for Glimpse from the Globe on the country, The Price of Independence and A Caspian Perspective. The realization that perhaps I had worn out my welcome was disconcerting, but I had no way to prove it. Given the recent crackdowns on journalists in Azerbaijan and elsewhere around the world, I wasn’t entirely surprised.

I had sent dozens of other emails over the prior months containing far more politically noxious prose than what was in the allegedly edited email. At the time, I had used the same email to send stories to my editors at Glimpse in the US. If someone was interested in censoring my opinions, those emails containing my stories could have been blocked. This curious incident led me to wonder: is a student publication like Glimpse really a threat to certain states? Was I making myself a persona non grata in a foreign country? Given the Obama administration’s policies for avidly investigating and prosecuting most leaks, could student writers be seen as a threat to their own government? When does one cross the line into professional journalism and begin to bear the attendant responsibilities?

(Glenn Halog/Flickr Creative Commons).

The State of Journalism

Even the most well-intentioned journalists can cause unintentional harm to their sources, themselves and to other third parties. When I went overseas, I went as a student with no intention of reporting at all. But as someone conducting research, I ran into problems similar to those encountered by professional foreign correspondents. Countless journalists have made valiant contributions to public discourse by reporting illegal government programs, wars, corruption and human rights violations taking place across the globe. As a result, some of these men and women have been imprisoned, injured and killed.

For example, Jake Hanrahan and Philip Pendlebury, a journalist and cameraman working for Vice News, were arrested in Turkey on August 27, 2015 and charged with filming near a military base without permission, along with their Iraqi translator Mohammed Ismael Rasool. Hanrahan and Pendlebury were then interrogated about alleged links to the Islamic State (IS) and Kurdish militants. Vice News stated that the duo had been filming skirmishes between Turkish police and Kurdish militants around Diyanbakir.

Hanrahan and Pendlebury have been released, but Rasool remains in custody despite continued uproar about his case. Robert Mahoney, a representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, decried “a worsening press freedom climate” in Turkey; Ankara’s moves against journalists have not been limited to isolated arrests. The Turkish government has launched an official investigation into Dogan Media Group for alleged “terrorism propaganda” through their use of IS promotional clips in new reports. Dogan is a part owner of CNN’s Turkish channel and the popular Hurriyet newspaper. Certainly, the Islamic State wouldn’t be so successful in its recruiting efforts without such broadcasted propaganda. But western-style outlets run by Dogan are not responsible for this. When they show clips of IS propaganda, it is to inform the general public about the horrifying atrocities the group has committed. Still, the charges brought by the Turkish government do compel us to reexamine what content professional journalists should and should not be reporting in mainstream media.

Responsibilities in International Journalism

Nonfiction writing depends on building a comprehensive story out of verified facts, and that can be a risky undertaking. A journalist’s most basic responsibility is to witness reality and put it into words. Foreign correspondents often serve as the sole sources of information for audiences in their home countries. These journalists have to be prudent about choosing what topics to cover. In addition to considering how useful any given information may be to an audience, the reporter also has to have enough confirmed facts to weave a readable, useful and complete story. In the case of Hanrahan, Pendlebury and Rasool, they decided that they needed to film near a military installation to communicate their content fully.

Some journalists are simply tasked with reporting events for the general public, and the readers can decide on their own how to interpret the information. Any introductory journalism class will emphasize the need for reporters to distance themselves from the story, and report every side of an affair equally and without bias. But today, writers commonly add their own analyses, opinions and predictions to investigative or informative pieces. Reporting and op-ed writing are not so distinct anymore. Vice certainly has a penchant for documenting the personal stories of people caught up in the events that are shaking our world, and they often let people speak freely for themselves. So should journalists condone or condemn the use of opinionated speech in contemporary media? There are strong arguments for and against it.

Prominent journalists like Glenn Greenwald argue that all writers are inherently biased in some way, and that instead of attempting to cover those biases in vain, they should be noted and used. No story is just the sum of its facts; people are affected by what happens in our world, and emotions and opinions tend to guide our responses. Perhaps these opinions are needed to have constructive dialogues about important issues.

On the other hand, maybe journalists ought to be less aggressive expressing political views. There are plenty of cases like that of Hanrahan, Pendlebury and Rasool. Other journalists have even gone so far to suggest that Greenwald’s own coverage of the NSA was criminal. In our global media era, journalists have to be wary of the laws of both their home nation and abroad. Political attitudes are important too; to my knowledge, I never broke any laws while doing academic research or reporting from overseas, but experienced some minor harassment nonetheless. In that case, the laws on the books didn’t matter so much as the informal perceptions of the government, and this is often the case in nations with restricted freedom of the press. The Vice team in Turkey were arrested on trumped up charges of being accessories to terrorism—an obvious ruse as there is no supporting evidence.

Whether or not to insert one’s own opinion into an article can be a dicey decision, and probably should be considered on a case-by-case basis. Political and social commentaries can be incredibly influential, and they can fuel political occurrences in and of themselves. At the international level, a journalist who unleashes any kind of opinion is bound to create enemies for him or herself, and that can be lethal. But journalists have a professional obligation to report the truth, and many are willing to take extraordinary risks to do so.

For a developing media outlet like Glimpse, determining when and how to allow correspondents to offer their own controversial analyses is an important responsibility. The words we write here as correspondents will shadow us for the rest of our careers. Student journalists need to be especially mindful of their futures as writers. We also need to be cognizant of the reality that we are not just observers of the world, but also part of it. That Heisenberg uncertainty may give us some serious challenges, but we must remain vigilant about maintaining our ethical and journalistic standards, even if it costs us a little cyberbullying along the way.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.