The Only Man Who Would Vote Against Putin

In late March 2014, after bloody fighting in Ukraine, the government of Russia approved the annexation of Crimea following an organized referendum by the residents of the peninsula. A vote held in the Duma, the lower house of Russia’s parliament, was widely expected to be a symbolic and meaningless approval of a decision already made. It was; members of Parliament (MPs for short), hardly eager to disagree with Russian President Vladimir Putin, endorsed the annexation by a count of 445-1. Called a “chilling message” by UK Prime Minister David Cameron, and a “robbery on an international scale” by Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, Putin announced the thinly veiled land-grab on March 18, 2014.

Ilya Ponomarev, an MP from Novosibirsk, the largest city in Siberia, cast the single dissenting vote to the acquiescence of 445 of his fellow legislators. In an exclusive interview with Glimpse from the Globe, Ponomarev offered his plans as an opposition leader for the political and economic future of Russia, a revolutionary perspective on Putin, and a scathing criticism of US policy towards Russia.

At the age of 14, the Moscow-born entrepreneur began working for the Institute of Nuclear Safety. By 23, he was Vice President of Yukos, an oil company run by the billionaire oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a staunch political opponent of Putin who was imprisoned by the leader for nearly a decade beginning in 2003. Yukos’ assets were seized and sold by the Russian government, and Ponomarev narrowly escaped the company and avoided being thrown in jail. After he left Yukos, Ponomarev launched an illustrious political career that has included a five-year stint as Chief Information Officer for the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and culminated in his election to the Duma in 2007.

Since his vote against the Crimea annexation, Ponomarev has been officially banned from Russia on charges that he used money from the Skolkovo Foundation, which supports technology startups, to fund anti-Putin protests. Foreign Policy reported that he still votes in the Duma by having friends smuggle his voting card into the country. Ponomarev currently lives in Santa Barbara, California, fearful of imprisonment – or worse – if he returns to Moscow. The recent shooting of fellow opposition leader and Putin-critic Boris Nemtsov within sight of the Kremlin proves that his fears are not entirely unfounded. In Russia, it is historically dangerous to be a man like Ponomarev. Before Nemtsov, the poster child was ex-spy and known Putin critic Alexander Litvinenko, assassinated in London after drinking a cup of tea filled with radiation poison allegedly by Putin henchmen.

But Ponomarev isn’t phased by any of that: from behind bright blue eyes that betray his eagerness and ambition for change in Russia, the 39-year old began by dispatching the conventional wisdom surrounding the psychology of a man who has kept Russia under his thumb for over a decade: Vladimir Putin.

Once a Spy, Always a Spy

“There is a misconception in the West that the guy is a long term thinker and great strategist with strong character,” Ponomarev told Glimpse. “I think he is none of that.”

For Ponomarev, understanding Putin begins by understanding his background, and specifically his time at the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, better known as the KGB, the police force of the Soviet Union until its breakup in 1991. During the 1980s, Putin worked in East Germany as a paper-pushing officer based in Dresden.

“His professional training as a KGB officer was targeted specifically to him not being able to make any decisions, but to make short term analysis of the data he was given from personal conversations with people, and relaying that data upwards for his superiors and the political leadership of the country,” Ponomarev explained. “None of the KGB officers were ever supposed to make any decisions. They were the implementers of policy, but not those who designed the policy.”

According to Ponomarev, the KGB served as a front for the Soviet Union to employ people who were judged unfit for crafting public policy.

“The policy was designed in the communist party, not in the security forces,” he elaborated. “The KGB was a process to pick up those who were not prepared to be in the policy process.”

Ponomarev said Putin’s shortsightedness as a leader stems from a KGB culture that preached making snap decisions and acting reactively instead of proactively. He pointed to Putin’s management (or lack thereof) of the Ukrainian Civil War as a crowning example.

Massive protests began in Ukraine in November 2013 when the cabinet of pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych scrapped a trade agreement with the EU and publicly advocated closer ties with Moscow. In 2014, the protests turned deadly, with pro-European Ukrainians clashing with both the government and pro-Russian rebels in the country’s east. Much to Russia’s disappointment, however, the pro-European movement won control of Ukraine’s government in national elections. In response, Putin orchestrated the annexation of Crimea, a predominantly ethnic Russian peninsula in Ukraine’s south. Ponomarev, the only MP in the Duma who voted against the annexation, said seizing Crimea was more of the same short term thinking that has come to define Putin’s reign of Russia.

“I think that from the very beginning our foreign service totally overslept the whole thing with [the]European association of Ukraine,” he argued. “When the revolution in Ukraine happened, he [Putin] went into Crimea without thinking of the long term consequences for that, but just with one desire: to overshadow the defeat he experienced in Kiev.”

Ponomarev said Putin’s propensity to react rashly is visible in other policy decisions, like his response to the Magnitzky Amendment, a round of sanctions passed by the US in 2012 and imposed on select Russian officials to punish them for human rights violations—namely the 2009 death of a lawyer named Sergei Magnitzky in a Russian prison. Putin responded by passing a law banning Americans from adopting Russian children—a reaction that distracted the media, captivated and diverted public attention, and had nothing to do with the original initiative on the part of the US.

“That’s very powerful manipulation technology that Putin is a master of,” Ponomarev told Glimpse.

Ponomarev highlighted the most powerful manipulation weapon in Putin’s arsenal: his recurring narrative to the Russian population that acknowledges his corruption and oppressiveness as a leader, while reminding Russians that he is infinitely superior to the post-Soviet Union Russian leaders of the 1990s like Boris Yeltsin, whose resignation in 1999 ironically paved the way for Putin’s first presidency. The strategy has worked; in Russia today, the 1990s evoke memories of a dismal economy and political turmoil, difficulties that many Russians blamed the US for due to its role in breaking up the Soviet Union. Polling data from as recently as 2010 reveals that 59% of Russians still believe the Yeltsin years brought “more bad” to Russia, when given “more good” and “don’t know” as alternative responses. Ponomarev said Putin tacitly acknowledges his shortcomings—but thrives on knowing Russians believe Yeltsin was worse.

“He [Putin] never says, ‘I am good.’ He always says, ‘Yes, I am bad, but others are worse than me,” Ponomarev continued. “He [Putin] has this example of [the]90s where he says to Russians: ‘A lot of my people are corrupt, but look at what was going on in [the]90s. Do you want to go back to that?”

As a result of pro-Putin public sentiment – both genuine and manufactured – opposition leaders are forced to work behind the scenes to avoid criticism and punishment. Ponomarev, who’s face appears on Putin-ordered posters in the center of Moscow behind the banner “NATIONAL TRAITOR,” prefers an opposition that seizes the headlines to one that works from the shadows.

“I think that’s one of the reasons why it is so hard to be successful and to receive enough direction in the general public,” he said. “It would be dangerous in the long term opposition of Russian interests to convince them [opposition leaders]to step back and go into the shadows and not be in the front lines of the newspapers, because people are afraid of them and think they will go back to Yeltsin types.”

With this observation, Ponomarev began to tell his story of opposition and outline his ultimate goal: to unseat the master of manipulation.

The Fates of Thousands

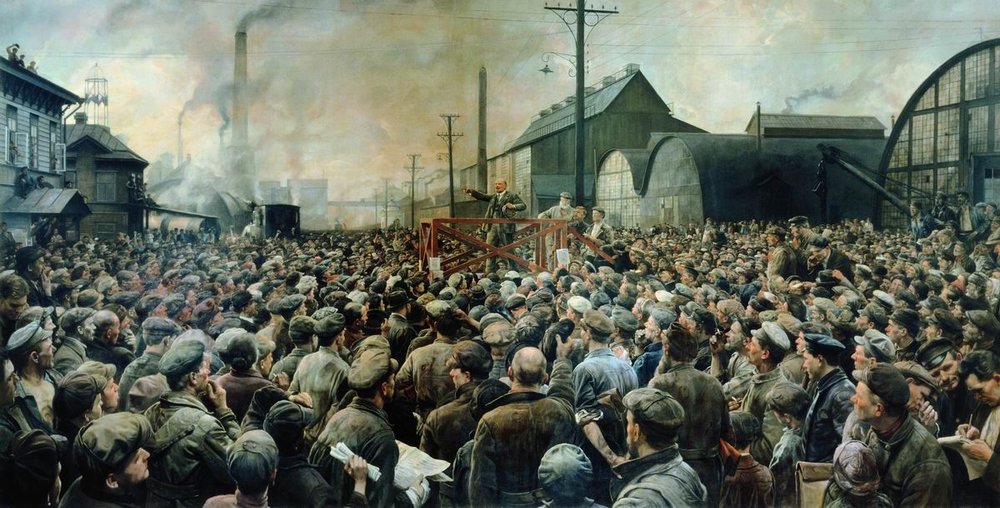

In 1905, the first of three Russian revolutions resulted in a limited constitutional monarchy that reduced the power of the Czar and established a parliamentary body called the Duma, of which Ponomarev is now an MP. Beginning in 1917, rebel forces in the second Russian revolution capitalized on a population exhausted from war, oppressive labor laws, economic depression and widespread government corruption to depose Czar Nicholas II and install a provisional government. A few months later, Lenin and the Bolsheviks, a smaller and more radical revolutionary sect, overthrew the provisional government and eventually formed the Soviet Union in 1922, marking the end of the third revolution in two decades.

During his time in the KGB, Putin kept a picture on his desk of Yan Berzin, a Bolshevik revolutionary who founded the Soviet military intelligence agency. In 2000, he marveled at the similarities between the Bolshevik rise to power and his own ascent to the head of Russia’s government.

“I was most amazed by how a small force, a single person, really, can accomplish something an entire army cannot,” Putin said. “A single intelligence officer could rule over the fates of thousands of people. At least, that’s how I saw it.”

Ponomarev plans to reincarnate the Bolshevik strategy to unseat Putin.

“A small group of political activists, if they are radical enough and if they have messages which are popular enough, can organize with people, crack the power, and seize all of it,” Ponomarev argued. “There was a very marginal sect of Bolsheviks who at best in 1914 had 10,000 members in the organization. Three years passed, and that small political sect was able to claim the power because of economic crises the country went through, power [shifts]the country went through, because of the war, and the crisis in management. This is exactly the crisis we see developing now in Russia.”

Ponomarev recalled the writings of Antonio Gramsci, a founder of the Italian Communist Party who was imprisoned during the Fascist regime of dictator Benito Mussolini. In his “prison notebooks,” Gramsci reflected on the success of a communist revolution in Russia and the failure of similar attempts throughout Europe. Ponomarev summarized his writings as follows:

“He was pointing out that when you have solid civil society and institutions, they balance the power and they create a lot of internal communication channels between the power and society and channel people’s activity in a productive manner.”

Ponomarev indicated that creating those institutions in Russia is essential to the success of the opposition’s effort to replace Putin. He said his personal future in a potential transitional government depends on it.

“The ultimate goal is to change the system in Russia and to come to power,” he declared. “That is the obvious goal for every politician. I myself am no exclusion.”

But in Putin’s Russia, Ponomarev said achieving change through a parliamentary takeover is nearly impossible.

“I am [an]elected official member of the parliament, so I am not neglecting usual normal political ways of getting into power,” he remarked. “But I can also testify that the role of the current parliament in modern Russia is so diminished so it is virtually impossible to accomplish anything, even if you control the entire parliament…even if by some miracle we [the opposition]achieve this [revolution], we would still be able to do nothing without controlling the executive.”

He holds the same realistic attitude toward achieving change through local and municipal elections. Ponomarev described a recent local election in which the elected opposition figure had his entire budget stripped by Putin:

“This spring, despite fraud and pressure and injustice, we managed, for example, to come to power in the largest municipality in Russia,” he said. “As soon as he took an oath in his office a couple of months later, they [Putin] changed the law that regulates income for the city and diverted the income from the city to regional authorities, which are controlled by United Russia [the current ruling party in Russia]—so now our elected mayor is sitting penniless.”

As Ponomarev told these stories, it became clear that the chances for achieving change in Russia through conventional political means are slim. Ponomarev said that given those conditions, change in Russia must come through more drastic measures:

“All our hopes for real changes are with a revolutionary way of changing,” he told Glimpse. “I hope it will not be a violent revolution, but still a revolution nonetheless. What I’m working on is in creating the basis for it, and I think that the basis consists for two parts: organizational structure and political platform.”

He said the organizational structure is being created and refined by his former boss and friend at Yukos, Mikhail Khodorkovsky. While he lives in the US, Ponomarev is developing a plan to “organize former USSR dissidents and entrepreneurs to create a political platform and future of Russia after Putin.”

“We believe in a small government, we believe in power to the people and to the local communities, which would be the ultimate source of power, we believe in the separation of powers, we believe in the rule of law, we think that we have to de-monopolize the economy and foster as much competition as possible,” he said.

“We think that the main value in the society is innovation and technological development which is coming out, and lastly we think that Russia does not need that almost-czar style president, but that it needs more of a parliamentary republic and a federalist system and the power cannot be concentrated in one hands.”

The success of that platform rests on the future (and continued failure) of the Russian economy. If profits from oil sales continue to decline, then the possibility of deposing the current leadership increases. Ponomarev said that regardless of the revolution’s (and the economy’s) success or failure, the organization of Russian civil society is cause for extreme concern.

The Deterioration of Russian Society

According to Ponomarev, the Russian economy faces a turning point.

“What was proclaimed all the time by Russian leadership in general…was to try to capitalize on oil generated wealth to diversify the economy and to modernize it and to go forward in innovations,” he began.

The cracks in that plan are clear: any discussion of continued oil wealth in Russia is mostly smoke and mirrors, and modernization in Russia has ceased; entrepreneurs like Ponomarev have moved their businesses abroad in search of a more politically and economically friendly environment. An entire generation of Russian businessmen and women fear financial and personal ruin, in the style of Yukos and Khodorkovsky, if they are perceived by Putin to be as politically threatening as they are economically successful.

“Right now, what we fear is that all of these discussions about modernizations have not just stopped, they have actually reversed because Putin is seeing all those entrepreneurs and medium/small sizes businesses as the political opposition,” Ponomarev lamented. “The middle class is his natural enemy.”

Demonizing the middle class has come at a great price: Putin’s oppression of political dissidents (and as a consequence, many entrepreneurs) has caused a brain drain of scientists and businesspeople, those who could ordinarily use their skills to stimulate the Russian economy.

“The emigration from Russia this year went up five times than it was last year,” he said. “I am very much afraid that it is a conscious decision by Putin – he is not Stalin and turning people to labor camps in Siberia – he [Putin] is incentivizing them to leave the country and is building a welfare state that relies on oil generated income and nothing else,” Ponomarev said.

But Ponomarev is faced with a dilemma: on the one hand, the Russian economy is rotting from within. On the other hand, the havoc wreaked by the brain drain and declining oil prices increases the success of efforts to topple Putin. If Russian history is any indication, the one thing rotten economies do produce, en masse, is political unrest. For Ponomarev, it’s a necessary evil.

“It is very bad for [the]country, but it is not that bad for the opposition actually because it just speeds up the process of deterioration of society and collapse of the current power,” Ponomarev explained. “Really, I feel very much sorry for my country [since]when I see all those talented, most capable and bright [Russian] individuals in the US or Europe. I meet them outside Russia.”

In the midst of his efforts to organize opposition to Putin, Ponomarev said policymakers in the US seeking to rein in Russia’s corruption and human rights abuses can and should reassess their current policy.

Towards Effective US Intervention in Russia

As Ponomarev sees it, US politicians who design policies to pressure Russia pander to the political desires of their constituents rather than designing effective sanctions, Ponomarev said. While predictable, he contended that the desire for politically “sexy” headlines has clouded their judgment of effective intervention in Russia.

“US policies in general are very much focused on the internal perception of the public, you know, what needs to be done,” he noted. “All the stories are more like [the]US pretending that something is happening, but is really not what is needed to change the situation.”

Ponomarev pointed to a preferred buzzword of politicians: sanctions, a longtime favorite policy of lawmakers seeking to prove to constituents that they are doing something, anything, to resolve an international problem that often deserves a far more nuanced solution. Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, both international economic penalties and US sanctions, approved both by President Obama and Congress, cut off Russian banks from US financial markets, imposed travel bans and froze assets of select individuals in the Russian government. Ponomarev said the sanctions are used by Russian elites, namely Putin, to reinforce their power and construct a narrative of anti-West hatred that is readily gobbled up by the Russian public.

“The sanctions, the way they have been structured right now, they tend to hurt rather than to help, to consolidate the elites and the general public against the West and around himself [Putin],” he said. “They help to propagate [a]very simple message to people: ‘America is our enemy, the prices go up because of America’s wrongdoings, they want to put us on our knees.’”

Ponomarev cast the personal sanctions that hit a select few Russian officials in a strictly counter intuitive light. He explained how Putin distributes money to sanctioned individuals from the budget, and even said that Russian officials whose names didn’t show up on the sanction list secretly compete with each other to make their name known in the US so that they too will be sanctioned and compensated by Putin with Russian taxpayer dollars.

“People inside the country are competing to be on that list because when you have say, 100 people, it’s easy to compensate them with government contracts and appropriations, and that is exactly what is happening,” he explained. “Those people on the sanction list either receive promotions or financial help on behalf of our taxpayers.”

To correct the backfire, Ponomarev urged US policymakers to broaden sanctions to a wider circle of individuals in the Russian government and send a clearer message of support to the Russian public.

He put it plainly: “Frankly speaking, I don’t understand the American logic. “If you [US policymakers] say, [‘punish] everyone who is involved in Ukrainian crisis,’ well the government has voted for the war in Ukraine. You are supposed to have all Russian deputies to be on the sanction list, but that is not the case. To make them move, you need to apply those sanctions against a wider circle of people, including those who do not have any visible connections to the decision making process. If you sanction all government [officials], at least then those people who have nothing to do with Ukraine would start asking questions. Those questions would not go to US, they would go to national leadership because they are the source of the problems to them.”

Ponomarev advised combining this with a policy that makes it much easier for regular Russian citizens to travel in and out of Europe and the US, to paint the West in a more positive light to Russians.

“I would, for example, restrict all government workers traveling to US and to European but make those travels as easy as possible for regular people to create the grounds for transitional changes, and position America as a friend rather than an enemy,” he said.

In the ultimate sign of counter productivity, Ponomarev said the ineffective and incoherent connection between US leaders and the Russian public is manifesting itself in the Russian public’s view of the Ukrainian revolution.

He described the backfire this way: “No one in Russia believes we are fighting Ukrainians, they believe we are fighting Americans and protecting Ukrainians.”

It is precisely that insight – and the ability to interpret it – that makes you believe Ponomarev isn’t just an everyday blustering politician with too much bark and no bite. He is, after all, the only man who dared to vote against Putin in the annexation of Crimea. He has a deep understanding of Putin and an acute awareness of the problems that plague Russia. But expectations must be tempered with reality: for as much as he understands Putin, Ponomarev knows that his political and unabashedly revolutionary strategy locks horns with a man who has kept a stranglehold on power for far longer than anyone would have expected. But one thing is for certain: situational factors in Russia are unsustainable. Win, lose or draw, something big is going to happen for the opposition in Russia, and Ponomarev is the man to watch.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.