The Crimean crisis has faded from headlines as flashier issues, such as IS and Ebola, have cropped up in the foreign policy sphere. Yet, the crisis is by no means resolved. At the November G-20 summit, the European Union (EU) threatened to impose further sanctions on Russia if President Vladimir Putin did not stop aiding pro-Russian separatists. Far from cooperating with demands, Putin reacted by leaving the summit early, perhaps in response to brusque, patronizing rhetoric. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper said to Putin, “I guess I’ll shake your hand but I have only one thing to say to you: you need to get out of Ukraine.” Neither sanctions nor such blunt demands have had any impact on the Kremlin’s policy; it is time for Western nations to reevaluate their approach to Russia.

To understand the current frayed state of diplomatic relations between Russia and the West, it is necessary to delve beyond current tensions. From its birth, Russia has been characterized by a tendency towards empire; expansionism is embedded in its roots. From the 16th century, all rulers remembered as “great” have pursued territorial conquest—Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great and Catherine the Great, to name a few.

To this day, the nation continues to measure glory in terms of conquest. Though Crimea stands as the most recent example, the satellite nations of the Soviet Union and a messy history of involvement in petty wars in the previous centuries illustrate this national tendency. This quality is also characteristic of the Russian people, not only the government. According to an August poll conducted by the Levada Center, a Russian independent polling and sociological research organization, 73% of 1,600 respondents from 134 Russian cities and towns supported the annexation of Crimea.

Nationalistic pride combined with a long-standing inferiority complex also characterizes Russian culture, manifested as a need to prove itself equal to the West. Born in the days of Peter the Great, this fear of appearing “backwards” – less powerful and developed than the West – has leaked into the international realm in the form of aggressive foreign policy.

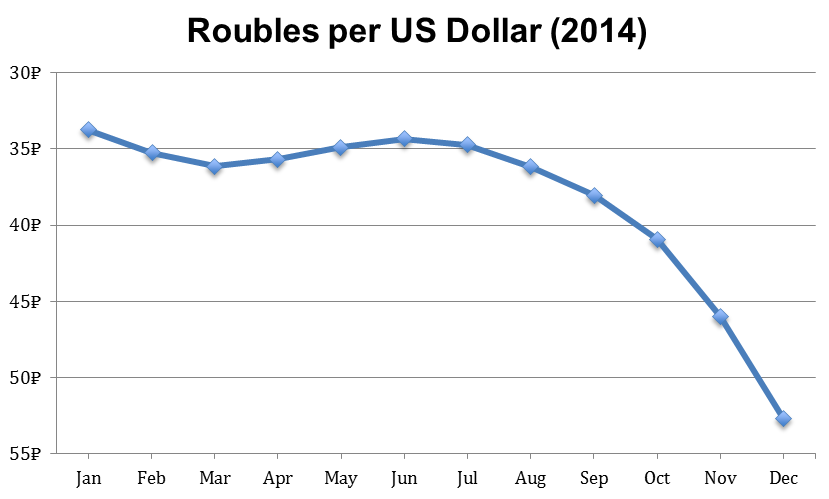

This brings us to the infamous Vladimir Putin. According to the Levada Center, Putin’s approval rating stood at an impressive 85% in November despite Western sanctions, a sluggish economy, rising inflation and unemployment rates, and a widening trade deficit. In October, The Economist called Russia’s economy “on the edge of recession” due to “state-imposed stagnation” fuelled by Putin’s refusal to adopt a new economic model based on innovation and investment “because of its troublesome political implications.” And now, Western sanctions “dramatically accelerated the worst-case scenario” for the Russian economy, already at risk of falling into “a cycle of low or zero growth, high inflation and rouble devaluation.” The combined effect of sanctions and falling oil prices have wreaked havoc on the rouble, which now stands at a record low exchange rate against the dollar.

But despite evidence that Western sanctions are weakening the Russian economy, 92% of Russians have not noticed an impact on their own lives, according to an August survey conducted by the government-run Russian Public Opinion Research Center. Though the poll may have been manipulated in favor of Putin’s administration, its results can still provide insight into his high approval rate. Perhaps the data is skewed; perhaps Putin’s propaganda has convinced Russians that sanctions do not hurt their country; but perhaps the sanctions’ impact simply has not trickled down to the level of the individual, even as they affect the economy as a whole. Even if the sanctions were having a noticeable effect, in the short term the Russian public would be more likely to blame the West than Putin. Already distrustful of Western leaders’ policies toward Russia, the people would perceive sanctions as the latest ploy to detail their country’s development and prosperity.

Meanwhile, Putin continues to channel public frustration against the West and assert Russia’s dominance. At the October 24th meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club, the Russian president delivered his latest anti-American diatribe. He accused the West, particularly the US, of hypocritically opposing his actions in Ukraine, which he defended as protecting Russian interests against “neo-fascists.” Putin appealed to a familiar metaphor, reaffirming Russia’s commitment to remain the regional hegemon: “The bear will not even bother to ask permission. Here we consider it the master of the taiga. It does not intend to move to any other climatic zones. However, it will not let anyone have its taiga either.”

On November 23rd, a state news agency published an interview in which Putin blatantly expresses a distrust of the West. Speaking to recent sanctions and general Western hostility toward Russia, Putin said, “You think it’s over our position over east Ukraine or Crimea? Absolutely not! If it wasn’t for that, they would have found a different reason. It has always been like that.” In fact, his administration has a long-standing tendency to present a “vision of Russia as a besieged fortress.”[1] In 2004, Vladislav Surkov, Putin’s then-First Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration, was quoted describing foreign efforts to undermine Russia’s development driven by “the hatred of what they claim to be Putin’s Russia but, in fact, [is the hatred]of Russia herself.”[2] It is hard to gauge the extent to which the Russian population buys into this rhetoric, but the dominant tendency of the masses (certainly outside intelligentsia circles) is to accept the state narrative.

Such propaganda is politically useful to Putin because of the preexisting anti-Western bias of his Russian constituents. The President’s strong domestic support stems from the overarching belief that he has restored Russia to a formidable place in the world after the collapse of the Soviet Union, by asserting the new Russia’s power to the rest of the world. Since the 1990s, a consensus emerged in Russian foreign policy that Putin continues to adhere to now; two main tenets are that the nation must remain “the hegemon […] of its region” and “a great power in all facets of international activity.”[3] For this reason, bullying Russia with tough sanctions and bitter rhetoric may do the West more harm than good, encouraging aggressive retaliation instead of fostering cooperation. We have already seen that sanctions are ineffective; they will not change Putin’s policy and only support Surkov’s besieged fortress theory. But Western leaders’ use of hostile language may be hindering cooperation more than they are aware.

Though Russia must be taken seriously, Western politicians should avoid portraying the country as a symbol of evil and corruption. In a September speech to the United Nations General Assembly, President Barack Obama likened Russian actions in Crimea to the Ebola virus and IS in terms of security threats to the US. Though he was merely pointing out the issues most worrisome to Americans, the statement came off as abrasive, comparing the nation of Russia to a terrorist group and a deadly epidemic. Such rhetoric reinforces the Russian view of an antagonistic West and cannot possibly facilitate healthy relations. The Russian Foreign Ministry responded by calling Obama’s speech “a set of clichés and propaganda slogans.”

Comparing Russia to a terrorist group vilifies the nation and embarrasses it on a global scale. As the head of state of the US, a nation that carries great moral power in today’s world, Obama stripped Russia of legitimacy in the international realm. But Putin has shown himself unlikely to respond in the way Obama might hope: by toning down aggression in his foreign policy. On the contrary, Putin has since escalated the conflict, sending in more troops, tanks and military equipment into Ukraine in early November.

To develop a meaningful working relationship with Russia, we must thus rethink our tendency to hold the nation in automatic distrust and contempt. This strategy has only produced frosty relations and talk of a “Second Cold War” (a Wikipedia page exists for the term). We cannot alter the president’s style of leadership or the Russian people’s desire for a strong nation they can take pride in. It is in everyone’s favor, however, to strive for open dialogue with Russia based on reality and not a caricature portrayal of the other side. Even beyond resolving the Crimea crisis through a compromise suitable to all sides, learning to cooperate with Russia would bring a wealth of benefits. Russia has the potential to sway many pressing global issues, from energy to the environment and instability in the Middle East. If the West could break its habit of treating Russia like a natural enemy, then together we could work toward a safer, more prosperous world.

The views expressed by this author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.

Other Works Cited

[1] Leon Aron, “The Putin Doctrine: Russia’s Quest to Rebuild the Soviet State,” Annual Editions: Global Issues, 30/e (2014): 147.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid 146.