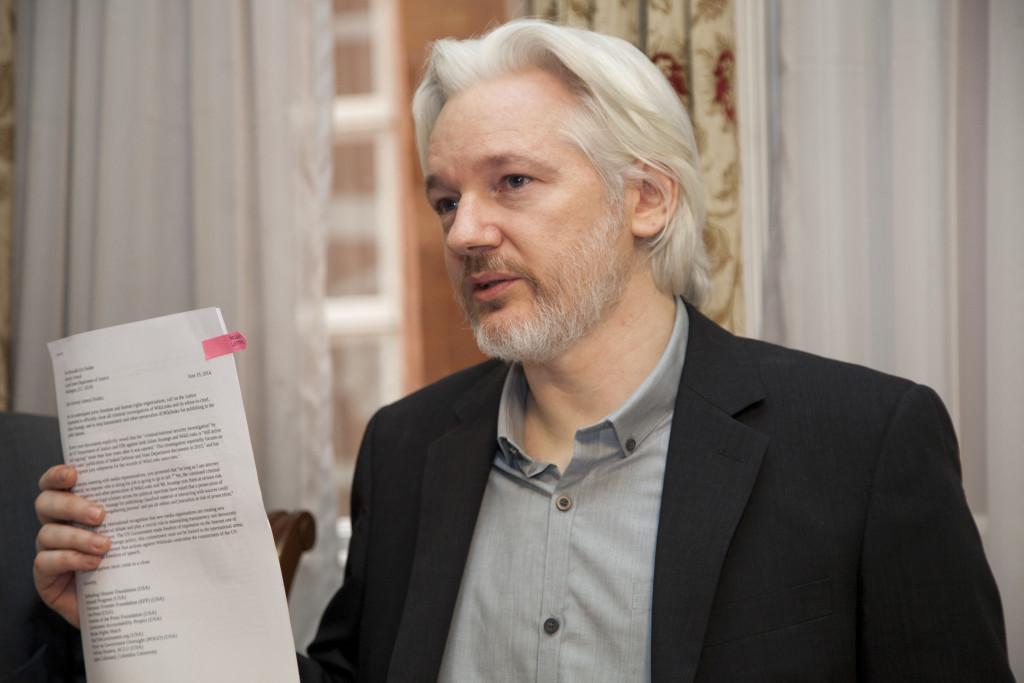

One morning in 2010, foreign governments and American officials around the world were faced with the possibility of a multipronged scandal. Each of the 251,287 US diplomatic cables leaked by Bradley Manning to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange potentially held an uncomfortable government truth, an identity or worse, a broken bilateral secret. Soon they would all be available in an online, searchable library—a nightmare for countries, companies and officials relying on the confidentiality of communications with the US, including the US government itself.

Diplomatic secrets—and their periodic breaches—are as old as the practice of diplomacy. The advent of the internet has arguably made these breaches more frequent. Since 9/11, information about US misdeeds and misconduct in its operations abroad has inundated the international public. As the press, whistleblowers and legal mechanisms reveal facets of US intelligence, surveillance torture and military operations, both foreign and domestic citizens resent their exclusion from the shadowy dealings of day-to-day foreign policy. After all, secret state-level negotiations between ostensibly open societies contradict democratic values. On the other hand, leaks like the 2010 Cablegate not only compromise US security, but also the security of every country represented in the information. Relations are weakened if countries are not guaranteed privacy in communications. Diplomats thus defend this routine privacy, not only as a security-enhancing, but also as a trust-building measure.

Not all secrets are created equal. There are two kinds of diplomatic secret – substantive and procedural. Substantive secrets are the ones that reveal key military positions and concrete information on government actions; these are generally the ones that stir global controversy. Procedural secrecy, however, is just that: the routine show of respect when discussing state affairs with international counterparts. Because of this two-dimensional secrecy, the diplomatic costs of illegal disclosures (leaks) can’t all be swept under the blanket argument of “national security” and compromising military data. When diplomatic information is leaked, countries lose trust in each other and suffer reputational costs.

For international politics, the most important difference among secrets is how they are divulged. Security and trust-building may explain why states keep secrets—but why would a state reveal its own secrets? Secrecy as a diplomatic institution makes information a threat when leaked but a tool when officially disclosed. Despite the disproportionate weight of their media attention, whistleblowers don’t have a monopoly on divulging secrets. In fact, disclosing previously classified information is a good-will tact used by state governments either to respond to international pressures or to ease longstanding tension with a particular state. Finally, normative information-sharing is promoted through legal mechanisms that allow citizens to request state documents.

In today’s push for international transparency and government accountability, these three major sources for disclosure have very different uses, or outcomes, for international relations. The following is a framework for analyzing the tools available for disclosure and their international implications according to type of source.

Uniformly Declassified Documents

Over 30,000 nuclear physicists, university professors and other white collar professionals “disappeared” in Argentina during the 1970s. They have since been presumed kidnapped by the military junta in power during the so-called “Dirty War”. Caught up in Cold War paranoia, the US was so consumed with halting the spread of communism that it saw leftist elites in Latin America as a threat to national security. Publicly accessible communications between Henry Kissinger and Argentine military officials suggest an implied support of the abuses.

The Argentine public has been clamoring for additional documents detailing specific US involvement in the military’s human rights violations. Just last year, when he visited Argentina on the national holiday commemorating those who disappeared in the Dirty War, President Obama announced a “comprehensive effort” to declassify the long-awaited documents. This has been called, by critics and admirers alike, “declassification diplomacy.”

Technically, the US has a program for uniformly declassifying documents once they reach a certain maturity. Under Executive Order 12958, older documents are automatically declassified after 25 years, and new documents, after 10. But the order, passed in 1995, was overridden by another executive order in 2003 under the Bush administration on Classified National Security. Consequently, it became more difficult for classified documents to become declassified.

Furthermore, to declassify a document (done only after a formal review process) does not mean to make it readily available. Once “released,” a document won’t necessarily get distributed to federal libraries, and may be subject to bureaucratic restrictions of access. Not to mention, when a document does become available to the public, it is hardly ever intact. Document images may be of a reduced quality and the content itself may be redacted.

Thus, in the case of the Dirty War, declassification as carried out by the government is more strategic than it is in the pure interest of transparency. Anti-American sentiment, widespread in Argentina, carries a resentment tied to a history of questionable involvement. While a leak of smoking-gun documents would have exacerbated existing tension, controlled declassification here allows the Obama administration to acknowledge the truth of past events.

Legal Recourse

The golden age of diplomatic transparency took place between the Soviet Union’s collapse and 9/11. During the international transparency movement that became known as the Decade of Openness, a total of 26 countries enacted formal statutes that guaranteed their citizens’ access to government information. In the US, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) allowed citizens, corporations and even foreign individuals to file requests for access to official documents. Movements like these represent a normative, international commitment to make foreign policy more democratic.

But after 9/11 this came to a screeching halt. Capping (and infiltrating) the flow of information was and remains a central, albeit controversial component of the War on Terror. Understandably, the public’s right to know took a back seat to the need for increased security. Now, a new wave of openness has begun to take shape—but the dynamics are much more complex than during the Decade of Openness.

In 2009, President Obama renewed FOIA’s guidelines, declaring that “in the face of doubt, openness prevails.” Still, this doesn’t always hold. Thanks to a court order in a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Obama administration released a policy procedure for airstrike operations on terror suspects. The 18-page document that was issued was nothing more than a redacted “factsheet” that described the content of the real document.

Legal action through mechanisms like FOIA will put pressure on governments to disclose, especially backed by claims to values like democracy and transparency. Most recently, FOIA was the mechanism that required the State Department to release inventories and broad descriptions to settle 35 lawsuits related to Hillary Clinton’s email.

But governments will still disclose on their terms. This means more redacted documents, like the airstrike policy, or more “inventories and broad descriptions,” which may not give a complete picture. Because legal demands are usually made by constituents, these disclosures are largely to assuage domestic audiences, and therefore play a lesser role in state-to-state politics, though they reveal key foreign policy information and carry potential threats.

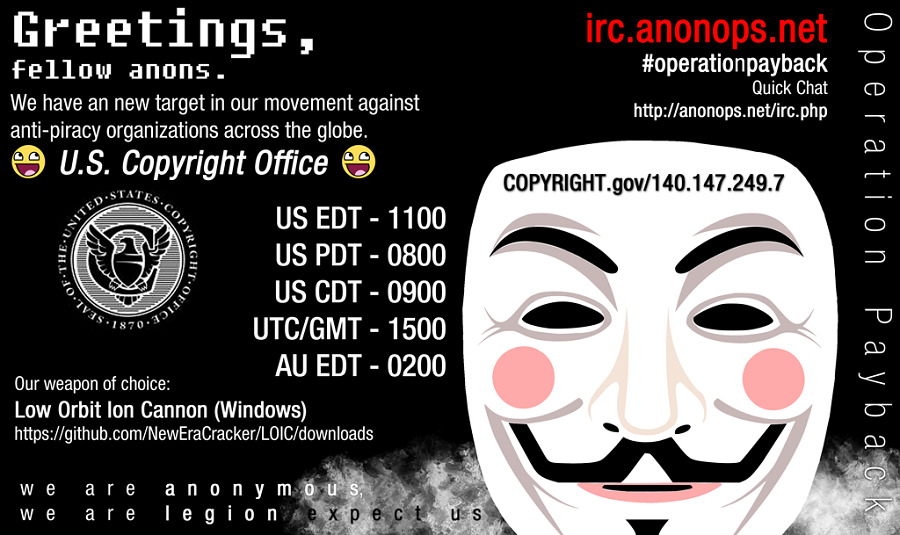

Leaks as Delivered by Whistleblower-Press Partnerships

Diplomatic consequences of illegal third party leaks are always initially catastrophic. A White House statement following Cablegate declared the leak “could compromise private discussions with foreign governments and opposition leaders, and when the substance of private conversations is printed on the front pages of newspapers across the world, it can deeply impact not only US foreign policy interests, but those of our allies and friends around the world.” On the other hand, a fellow at UK think tank Chatham House felt “governments have a tendency to try to keep as much information as possible secret or classified, whether it really needs to be or not. The really secret information, I would suggest, is still pretty safe and probably won’t end up on WikiLeaks.”

The most widely discussed disclosures are those carried out illegally by third parties. Because these revelations are conducted against the state government’s will, they are expected to be the most illuminating. Yet the dynamic surrounding them is contradictory.

The persistence of government restrictions on willingly disclosed, decades-old documents should translate to severe repercussions for any whistleblower or third party who leaks classified documents. Indeed, the repercussions have been severe for the likes of Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange. But put into perspective, throughout US history there have only been 13 criminal cases in which a whistleblower was prosecuted. Seven of these were prosecuted under the Obama administration, compared to the other six prosecuted by all previous administrations combined.

As information law scholar David Pozen observed, the US government is constantly denouncing the release of classified information by anonymous sources to the media, and yet laws against them are rarely enforced. When it comes to document leaks, the US government condemns by law, but condones in practice. This permissiveness, he believes, is a pragmatic response to the mistrust generated by the secret-keeping as well as to the over-classification and fragmentation within bureaucracies.

An image of transparency is perceived as a national interest and, depending on the international context, can be as important as national security. Pozen describes the US as “a polity saturated with, vexed by, and dependent on leaks,” and while the government makes a point of outwardly “vilifying leakers,” in reality it maintains “a permissive culture” of disclosures.

Diplomatic secret-keeping is in many ways a balancing act. For the same reason that Italy’s foreign minister called the WikiLeaks Cablegate scandal in 2010 “the 9/11 of diplomacy,” secrecy can never be completely erased from foreign policy. It may be the same reason why, when asked for his thoughts on US involvement in the Dirty War, President Obama responded to an Argentinian journalist saying, “I don’t want to go through the list of every activity of the United States in Latin America over the last 100 years.” State-guided disclosures are only as useful to publics (foreign and domestic) as the disclosing government wants the information to be. Calls for citizens’ right to know are legitimized on the basis of domestic open-society principles; but so are the implications of illicit and official disclosures on diplomacy conducted worldwide. Thus when any secret is divulged, trust, transparency and political consequences hang in the balance.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.