In my recent post, I detailed the history of American grand strategy and elaborated on its current failures. But jeremiads are useless unless they offer a path to salvation along with their forebodings of gloom. In this follow-up post, I will detail my strategic vision for the future of American grand strategy, which has been strongly influenced by Michael Lind, Adam Garfinkle and James Kurth.

Michael Lind argues that the purpose of American strategy is to protect the American way of life—that of a “democratic, republican, liberal” society. This society must possess a sovereign state, a republican political system and offer its citizens a democratic, middle-class lifestyle. The primary threats to this way of life come not from outside the United States, but from tyranny, corruption and plutocracy within. Not just conquest but also any foreign threat that could lead to an American response that undermines the American way of life from within is therefore unacceptable, and US foreign policy must prevent such threats from arising. The primary threats that might arise abroad are hegemonic regional empires – which, like Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan and the Soviet Union, might require a militarization of American society antithetical to the American way of life – and stateless anarchy, which breeds great transnational dangers.

Adam Garfinkle offers similar conclusions about the nature of international order in his concise article “Conservative Principles of World Order.” His three principles shed additional light on the principles Lind articulates in his work.

“American liberty as the measure of all things” means precisely what Lind argued in The American Way of Strategy. “International security through strengthened sovereignty” is similarly self-explanatory: to fight the ills that come with disorder, such as disease, terrorism, separatism and extreme poverty, and encourage the formation of modern states in every square mile of habitable territory on the planet. Lawlessness is a threat. “Live and let live,” specifically targets America’s penchant for placing human rights concerns before strategy. If there is to be a true world order, then America must be tolerant of those nations that espouse values far different from our own western ideas. This “genuine global multiculturalism” is prerequisite to any modern concert system.

James Kurth, in his fantastic article “Coming to Order,” adds additional commentary. First, when working with local power players, we must accept whatever is locally the most effective way to organize and order society, regardless of how distasteful it might be to Western consciences. Second, the most stable regions are those dominated by some sort of natural hegemon – as the Western Hemisphere is dominated by the United States – and it would be most efficacious for the United States to cede order-forming responsibility to regional power players in every strategically significant region—Europe, Eurasia, the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia. This network of global partnerships would thus be a concert system, and the foundation of a usable system of world order.

Now onto my grand strategy.

My ideal grand strategy can be best summarized in the acronym “BOP COP.” BOP COP stands for “Balance of Power, Concert of Power.”

The Balance of Power component of BOP COP is the most classically Realist of its components. Its primary purpose is to ensure that no power or coalition of powers able to threaten the United States arises in any of the critical regions of the earth. There are three primary geopolitical imperatives, and a fourth corollary imperative, connected with this goal.

First, the United States must dominate its strategic theater of North America and the Greater Caribbean Basin. The existence of any power in this theater with interests hostile to those of the United States is an unacceptable threat. This need only be strategic dominance, not necessarily territorial dominance; thus, the well-integrated North American system of the United States, Mexico and Canada, wherein at present Canada and Mexico are integrated into the American continental defense network and political economy. American power in the Greater Caribbean Basin could use improvement, especially given the continued antics of the regimes in Havana and Caracas. However, overall American dominance there now ensures a stable theater for the United States.

Second, the United States must keep the five critical regions of the Eastern Hemisphere politically divided, so that no great hegemonic power can dominate any of them, expand and become a potential threat to the American homeland. These regions are Europe, Eurasia, the Middle East, South Asia and East Asia. Europe is reasonably united under the European Union, but this is more of a successful concert than a hegemonic power bloc, and the rival powers within Europe still compete at a low level. Eurasia is dominated by Russia, and US policy should accommodate Russian power while striving to ensure the independence of the largest of the former Soviet states. Russia is the go-to order-keeper of Eurasia, but it should not be allowed to grow too dominant. The Middle East is in shambles in the wake of the Iraq War, the Arab Spring and the eternal Sunni-Shia war. Turkey and Iran are rising to fill the gaps, and they should be balanced against each other, along with mid-level regional powers. In South Asia, India should be viewed as the rightful hegemon, as it functionally is right now, but great pains ought to be expended to ensure the independence of Pakistan. In East Asia, the United States should accommodate China and Japan as regional leaders, while balancing the coalition of the Philippines, Japan and Vietnam against the China-Korea-Myanmar bloc. This does not mean forward deployment and assuming security responsibilities for regional players: it means, instead, diplomatically aligning the proper blocs against each other to prevent the rise of any power in the Eastern Hemisphere that can threaten American dominance in the Western Hemisphere.

Third, the United States must ensure that those regions of the Eastern Hemisphere with strong, near-hegemonic powers are balanced against each other. This is particularly important as regards Russia in Eurasia, China in East Asia and India in South Asia, as each of these is sufficiently dominant to be nearly hegemonic in its own realm. They must be balanced against each other to prevent the formation of a grand Eurasian coalition.

The corollary to all this is that the United States must maintain the preeminent navy in the world. Other navies may exist and patrol their own spheres, but the United States Navy must maintain the ability to access every ocean and sea regardless of the predilections of regional powers that might want to deny it access. A world ocean vied over by competing great powers would make for a much less stable world; for the sake of world order, the US Navy must reign supreme.

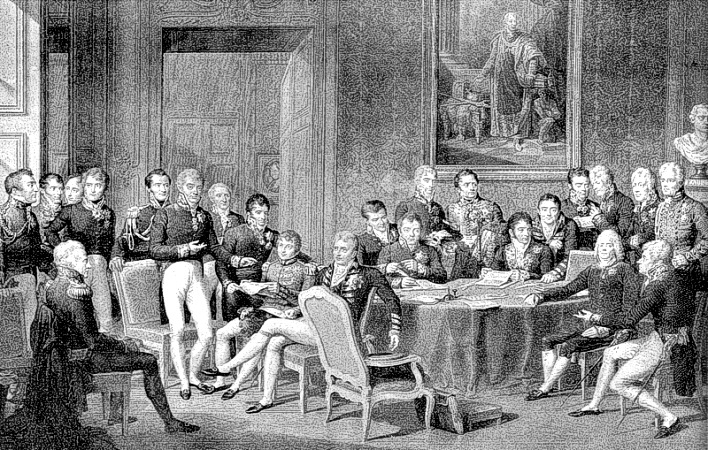

Though a Balance of Power system indeed underlies American strategy, the conduct of American grand strategy ought to be done through the prism of the Concert of Power system for ceremonial purposes, for the sake of decision making being done at the proper level, and to put some order to the chaos. The United Nations system is clunky and allows too loud of a voice for the smallest of states; it would be preferable for problems to be dealt with at the level at which they exist, and questions of world order primarily exist at the level of great powers.

The United States should utilize contemporary international organization architecture to formulate a series of Concert Systems for every critical region. Some of these concerts will likely overlap each others’ boundaries. What is critical is that a decision making system capable of reducing violence and resolving disputes exists at a local level in all critical corners of the globe.

The primary members of these concerts would be the great powers of every region, and particularly strong powers would be members of multiple systems. The United States, as organizer, would maintain membership in each concert, too. This would provide it with the means to exert influence in each region without attempting to dominate them.

The concert system is not meant to abolish war. It is meant merely to make more efficient the avenues for dialogue between critical powers. Rivalries and competition clearly must continue under the system; but, with a network of gentlemen’s agreements, nations holding true stake in the fates of their regions in the concert system could be infinitely more effective than the current UN system.

It is crucial that every state capable of maintaining internal order is invited into the broader concert system, and that the universal messianism that has heretofore colored American foreign policy be diverted. This is where the dignity of difference comes in; it is fruitless for the United States to attempt to change the internal constitutions of other nations with which it is trying to work. The United States can, however, encourage the cultivation of order, for once order is established law and liberty can follow. Proclaiming declarations of universal rights for the citizens of a country like China is more likely to be counterproductive to the Sino-American relationship and dispose both parties towards unnecessary ideological conflict. John Quincy Adams called America the well-wisher to the liberty of all, but the “champion and vindicator only of her own.” It would be wise to exist in concert with diversely different nations without attempting to alter the very nature of their societies.

Though the balance of power is ultimately unavoidable, it would be best managed by pluralistic concerts of states at the regional level. None of this is incompatible with international law and liberal internationalism. Indeed, under a global concert system the international system becomes more stable, and the law of nations that comes with it will flourish. It is incumbent upon our generation of statesmen to discern a prudent grand strategy for America that will put the United States in the best position abroad in our rapidly changing world.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.