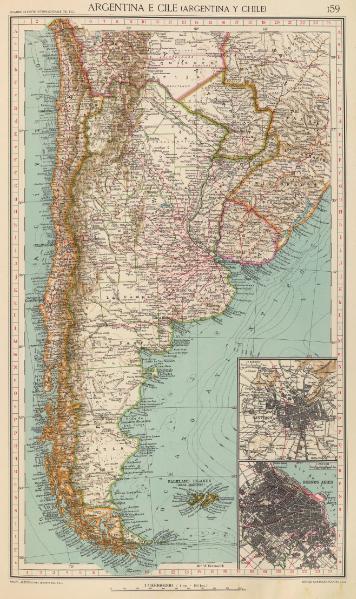

With the exception of commodity exportation, Argentina’s recent economic condition has soured. The last half-century has been marked by economic decline, political instability, and diminishing geopolitical influence. Consider that when President Obama visited the Southern Cone in 2011, he flew from Chile to Brazil deliberately passing over Argentina. While significant capital inflows from China largely insulated Argentina from the global economic crisis, economic and political turmoil persist to this day. Inflation estimates are above 30%, its expropriation of Spanish petroleum giant Repsol have made those in the international business community wary of FDI, and its export and import quotas have proven disastrous to farmers, businessmen, and consumers alike.

If President Kirchner’s successor seeks to guide Argentina towards a path of economic and political stability, he/she must assuage concerns of an impending crisis, and work swiftly to ignite a stagnant economy. Reviving the economy will be easier said than done in a country whose Ease of Doing Business ranking is 127 out of 189, trailing, among others, Nigeria and Pakistan. A more challenging hurdle will be reducing Argentinean dependence on natural resource exports. As tempting as it may be to ride the commodity wave to economic solvency, diversification of the nation’s income will prove imperative to Argentina’s future growth and stability. Developments in added-value manufacturing and the service industries will better isolate Argentina’s economy from fluctuations in global commodity prices. Diversification will also require improvements in education and infrastructure, areas in which Argentina is particularly deficient.

Attempts to curtail government spending will likely aggravate an already sluggish growth rate, particularly after several years of costly welfare programs and President Kirchner’s wasteful spending. Also unpopular will be the inevitable currency devaluation once Argentina’s currency exchange is liberalized. Such unpopular policies have been postponed for far too long. Argentina must follow in Chile’s footsteps by increasing economic competitiveness in the global arena. For a country blessed with bountiful resources, its political malfeasance and bureaucracy remains the only thing slowing down what would otherwise be impressive growth. By fostering more competitive industries and implementing basic economic reforms, Argentina may become the gold mine it once was.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff and editorial board.