Guarani Tribe Protests New Executive Order

Brazilian President Bolsonaro’s recently passed executive order has grave ramifications for protected indigenous lands in the Amazon. On January 18, 2019, the day of the first Indigenous People’s March in Washington DC, another group of indigenous people marched 4,000 miles away in Ubatuba, São Paulo. Representing 21 neighborhoods in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the group marched through the streets in opposition to President Bolsonaro’s executive order to transfer the National Foundation of Indigenous People (FUNAI) to the Ministry of Agriculture. The Guarani tribe demanded that lands already set aside for indigenous groups not be altered and also filed a lawsuit with the Federal Prosecutor’s Office to reverse the executive order.

Indigenous Land Rights in Brazil

Currently, there are about 305 indigenous tribes living in Brazil, which total to 900,000 people and constitute 0.04 percent of the Brazilian population. They live on 13 percent of Brazilian land, 98 percent of which is in the Amazon, making the conservation of these lands vital to the preservation of their culture. Although the Brazilian constitution recognizes the original indigenous ownership of all Brazilian land, it requires the government to physically mark these protected territories, which is one of the main responsibilities of FUNAI.

Created in 1967 and formerly overseen by the Ministry of Justice, FUNAI is the official indigenous organization of the Brazilian government. It coordinates and executes federal policies for all indigenous groups in Brazil and is responsible for the “demarcation, regulation and registration” of lands traditionally occupied by indigenous peoples. By moving FUNAI to the Ministry of Agriculture, Bolsonaro reduced its status and gave its oversight to an organization with a competing agenda.

NGOs and Indigenous Groups vs. Bolsonaro and the Farming Lobby

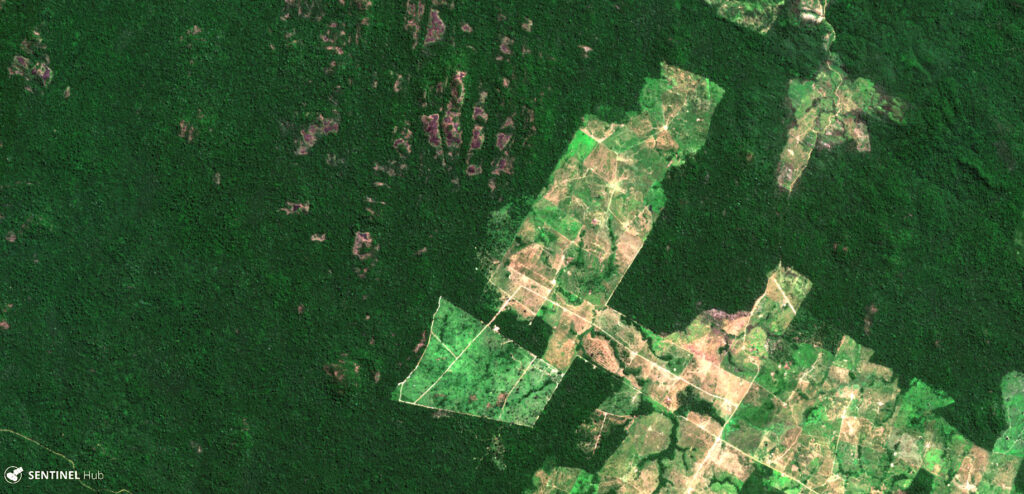

This move has created concerns to many indigenous and environmental groups as the executive order pushes Brazil toward a pro-farming agenda and away from the conservation of the Amazon and its indigenous lands. During his election campaign, Bolsonaro discussed the need for land reforms, stating that he wanted to change the ownership of indigenous lands from communally-held, tribal lands to smaller land parcels held by native individuals. This would empower these native individuals to sell their land to powerful agricultural corporations, who have been lobbying for years for access to the Amazon. Currently, cattle ranching operations as well as soybean, sugar cane, and palm oil farms are the leading cause of Amazon deforestation. With conservation of the Amazon so crucial to preserving indigenous land rights, traditions, cultures, and ways of life, any threat of deforestation directly impacts the people who depend on the Amazon and its resources.

As Bolsonaro pursues his pro-farming agenda, he is also limiting any potential resistance to his actions. In the same executive order which transferred oversight of FUNAI to the Ministry of Agriculture, he also gave broad powers to the Secretary of Government to “monitor and accompany activities” of NGOs working in Brazil. This action threatens many watchdog organizations as it gives the government the ability to restrict their activities if they oppose Bolsonaro’s agenda. Anticipating a backlash, the President defended himself in a tweet days after the order was issued, blaming NGOs for keeping indigenous people “isolated from true Brazil” and calling for their integration into Brazilian society.

Tereza Dias: Bolsonaro’s Pro-Farming, Right-Hand Woman

To help make Brazil more farming-friendly, he appointed Tereza Cristina Dias as the Minister of Agriculture, who is also an adversary to protecting the Amazon. As the only woman in his cabinet, Dias is the leader of the Parliamentary Front of Agriculture, a pro-farming congressional caucus with ties to agribusiness. During her time as a federal deputy in Congress from 2015 to 2018, she helped pass a bill that would legalize the use of pesticides. She also recently criticized model and Brazilian public figure Gisele Bündchen, a UN Honorary Ambassador for the Environment, for harming Brazil’s reputation by condemning Amazon deforestation “without knowing the facts.” Currently, she is under investigation for taking bribes from pesticide companies for her re-election campaign.

Economic Promises vs. Environmental Protection

Brazil’s economy relies heavily on its export of raw materials, with soybeans, iron ore, and raw sugar making up 47 percent of Brazil’s exports. Due to this reliance on raw materials, expanding large-scale farming and increasing agricultural productivity is a top priority for Bolsonaro, who promised to kick start the economy and achieve a budget surplus by 2020. However, the question is how far he will go in eroding indigenous land rights to achieve that goal and whether he will bend to public pressure from celebrities like Bündchen and legal action from indigenous leaders and environmental NGOs.

There are still constitutional protections of Amazon lands which prevent any outright confiscation of indigenous lands by Bolsonaro. However, only a weakened FUNAI stands between changes to tribal lands and coercion by the agribusiness lobby to sell these lands. Indigenous leaders’ only recourse would be legal action in Bolsonaro-sympathetic courts. Under Bolsonaro, Brazil is heading for the largest deforestation of the Amazon in its history.