Since Donald Trump’s surprising (depressing?) election victory, even more attention has been focused on Russian interference in the US election. The Obama administration officially accused Russia of interfering in the election on October 6th, and the reaction–by the US government, think-tanks and the general public–has been one of shock and anger. In a year marked by hostile, seemingly impassible party-lines, dismay at Russian actions and the need for a proportional response received bipartisan support. Ben Sasse, the Republican junior senator from Nebraska, claimed that “Russia must face serious consequences.” Rep. Adam Schiff, the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, urged the Obama administration to work with European allies in order to put forth a “concerted” response. His fear, he says, stems from the fact that Russia’s cyber-interference could have had an “election-altering effect.”

It very well might be criminal and undemocratic to interfere, in whatever capacity, in another country’s election. But for the US government to feign shock that Russia did this is either a case of blatant hypocrisy or very selective memory.

It is no secret that the US, via the CIA, has a long history of meddling in the electoral and democratic affairs of other countries, usually by fomenting violent coups against democratically-elected foreign leaders. This was especially true in the 1960s and 1970s. It was seen with Salvador Allende, Latin America’s first democratically elected socialist leader, where a coup led to his death in 1973, and with Mohammed Mosaddeq, the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, whose nationalist policies were only tolerated for two years before Western governments had enough. The sentiment of the time was properly summed up by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who purported to Nixon about Chile, “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”

The CIA essentially stopped funding these type of coups after the end of detente in 1979. But the US government’s fascination with and capacity to manipulate elections and leadership-positions in foreign countries didn’t simply die off. It continued, albeit using subtler mechanisms, influencing elections and democratic politics wherever it felt obliged.

One of these new mechanisms for influence/interventions was through programs such as the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). In the words of Allen Weinstein, one of the founders of the NED, “A lot of what we (NED) do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.”

The NED was established by Congress in 1983, shortly after Ronald Reagan’s famous “empire of evil” speech, where he called for the need to put in place the “necessary infrastructure for democracy” across the globe. It is a nonprofit, and technically non-governmental organization, though it began–and remains–largely funded by the government.

Its website writes about its “dedication to the growth and strengthening of democratic institutions around the world.” That’s a far kinder description than Ron Paul’s, the Texas Republican who called the NED “nothing more than a costly program that takes the US taxpayer funds to promote favored politicians and political parties abroad, [that has]nothing to do with promoting democracy and everything to do with destroying democracy. ” In this regard, Ron Paul accrues bipartisan support; Democrat Tom Harkin once asked the Senate if the US government and the NED “really want free elections and fair elections in Nicaragua, or [if they]want an election bought for and paid for by the United States government?”

The first sign that there might exist some divergence between the NED’s stated goals and ideals and their actual actions came about almost immediately after its creation, in the unlikeliest of places: France. In justifying the need for the NED, Reagan had stressed the necessity of promoting democracy in “totalitarian states,” or other regimes where democracy had yet to firmly plant itself. France, on the other hand, was one of the longest-standing democracies, and, having been founded on the idea of freedom and liberty, had about as strong democratic institutions and policies as the US. So it rightfully raised some eyebrows when the NED granted $1.4 million in funds to two institutions designated by the New York Times at the time as “center-right groups in France that have opposed the policies of President Francois Mitterand’s Socialist Party.” Though the NED has no formal “party affiliation” or official doctrine beyond promoting democracy, money was quickly and uncontroversially (within the US government and NED, that is) spent when there seemed to be a growing socialist presence in an otherwise perfectly democratic country.

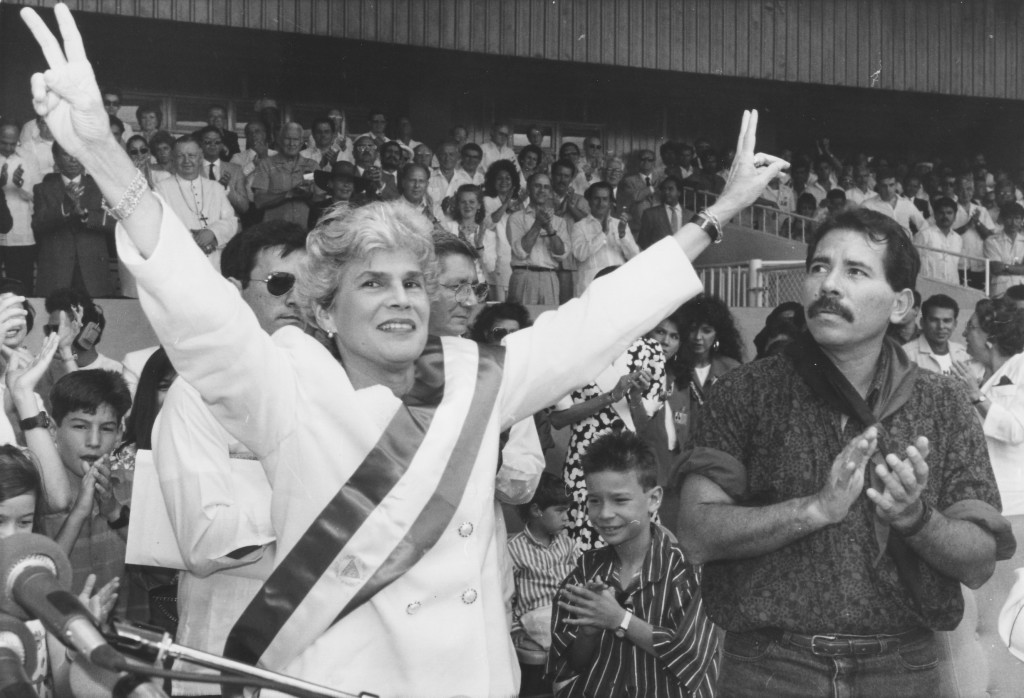

By 1988 and 1989, during the height of “containment,” a US cold-war policy to prevent the spread of communism, Congress appropriated money to the NED for two specific causes: assisting the “No Campaign” movement in Chile, and assisting the UNO democratic opposition in Nicaragua’s 1990 election. Having Congress appropriate the money and dictate the NED’s South American budget,worried even the President of the NED, Carl Gershman, who feared that being seen as an extension of the US government could undermine the NED and with it, its beneficiaries. (And he was right; in Chile some beneficiaries refused to accept the NED funding, believing the association with the US government more damning than the money was worth.)

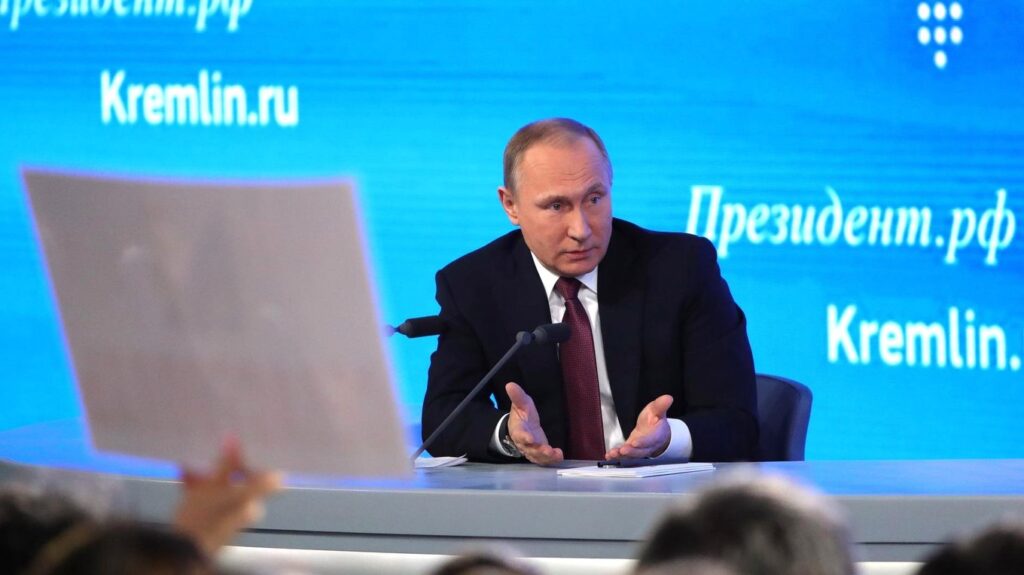

These potentially “election-altering” actions, in the words of Rep. Schiff, aren’t exclusive to the NED. Take for instance the USAID, a government agency whose aim is to “enable resilient, democratic societies to realize their full potential.” It was in part USAID’s actions during the Velvet Revolution that prompted Putin to accuse the US of creating, or at least manipulating, uprisings in Russia and its neighboring countries. The book “Foreign Aid and Foreign Policy: Lessons for the Next Half Century” credits USAID with expediting political transitions in Eastern Europe during the period. Further, the authors cite perceived partisanship as USAID’s biggest weakness, claiming that “US programs often align themselves with oppositional figures and institutions.” Regardless of the merits of these actions (and this article doesn’t dispute the fact that there are, indeed, merits), it isn’t hard to see why Putin might find recent claims of Russian intervention a bit hypocritical.

Nor are the actions exclusive to the 1980s and 1990s either. Early in 2016, an audio recording emerged containing an interview between Eli Chomsky, a writer for the Jewish Press, and Hillary Clinton. In the recording, Clinton says bluntly “I do not think we should have pushed for an election in the Palestinian territories. I think that was a big mistake. And if we were going to push for an election, then we should have made sure that we did something to determine who was going to win.” (In fact the US had intervened. In 2006, the New York Times reported that the US government was currently discussing ways to “destabilize the Palestinian government so that newly elected Hamas officials will fail and elections will be called again.” They frequently contacted Palestinian Authority (PA) president Mahmoud Abbas, trying to get his help in annulling, or delegitimizing, any election in which Hamas gained power. Unfortunately, Abbas believed it to be hypocritical if the US and the PA backed away from democracy now, and furthermore believed the election could coopt Hamas into moderate Palestinian politics. But, clearly, Clinton still didn’t believe enough had been done.)

Now, imagine an elected Russian official saying the same thing about the US election. The reaction of disgust and shock would reverberate across Washington. D.C. Senators and Congressman that were upset by Hillary Clinton’s leaked emails or Tillerson’s nomination could very likely call for war if they heard something similar from the Kremlin.

As surprising as the content of the quote is, more surprising is her willingness to unabashedly declare that the US has the capability and will to ensure an outcome of foreign “democratic elections” in public. Repulsive as Hamas’ ideals and policies are (it is a terrorist organization after all), it is quite shocking to hear an elected official suggest fixing foreign elections. The US had pressured Palestine for years to hold a fair-and-transparent election under the premise of “democracy” but then declared that the outcome shouldn’t have been accepted unless the preferred party of the US wins.

Now, this isn’t to suggest a parallel between Russia helping Donald Trump, a nativist demagogue, and the US hurting Hamas, a terrorist organization. In fact, I don’t even suggest that there was something morally culpable with attempting to fix the election against Hamas, or that there is something wrong with (proportional) retaliation against Russia now. What I am suggesting is that the world’s superpower can quite assuredly set precedents for rising powers to follow, willingly or not. To spend countless time and money on electoral interference abroad to suit domestic needs/ideals, and to have it work, is inviting other countries to do the same when their strategy or policies are put at risk.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.