On August 25, the world received a piece of good news from the public health sector: the continent of Africa eliminated wild poliovirus. However, the overall global fight against polio is still raging, and the coronavirus epidemic is only exacerbating this challenge.

As defined by the World Health Organization, poliomyelitis — known as polio — is a highly infectious viral disease that attacks the brain and spinal cord, resulting in total paralysis in many cases. In the early 20th century, polio was one of the most feared diseases. The virus devastated communities around the globe, causing thousands of cases and deaths. One outbreak within the United States resulted in 58,000 cases of the disease and 3,000 deaths. However, in the mid-1950s, the scientific community gained a greater understanding of the poliovirus thanks to the research of doctor and virologist Jonas Salk. In 1953, Dr. Salk made a promising break in polio prevention research, and by 1955 he had developed the first effective vaccine against the virus. Soon, international efforts to eliminate the poliovirus were established, such as the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which continues to work to eradicate the virus worldwide.

Since the initiation of coordinated efforts across Africa to combat poliovirus began in 1996, the region has prevented life-long paralysis in up to 1.8 million children and saved approximately 180,000 lives. One of the most prominent efforts was the ‘Kick Polio Out of Africa’ campaign, championed by late South African President Nelson Mandela and supported by Rotary International. This campaign motivated African leaders to help the polio vaccine reach every child in Africa. Today, approximately 220 million children in the African continent are immunized against polio annually.

This milestone achievement of eradicating wild poliovirus from Africa comes after numerous decades of analysis, research, immunizations, and polio surveillance in the region. This is only the second time in history that the African continent has successfully eradicated a major disease, the last being smallpox 40 years prior. The elimination of wild poliovirus from Africa brings the international community one step closer to accomplishing the worldwide eradication of polio.

However, the threat of the poliovirus still is ever-present in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The World Health Organization and partners from the Global Polio Eradication Initiative have committed themselves to assisting the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan as they tackle the virus’s final strongholds. Since 2015, no cases of wild poliovirus have been detected outside of Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. In 2019, a total of 176 wild polio cases were reported in these countries, with Pakistan accounting for 84% of the cases, representing a significant increase from the 33 cases reported worldwide the year before. Since eradication of polio is an ‘all or nothing’ effort, failure to completely eliminate polio from these regions could result in a resurgence of the virus.

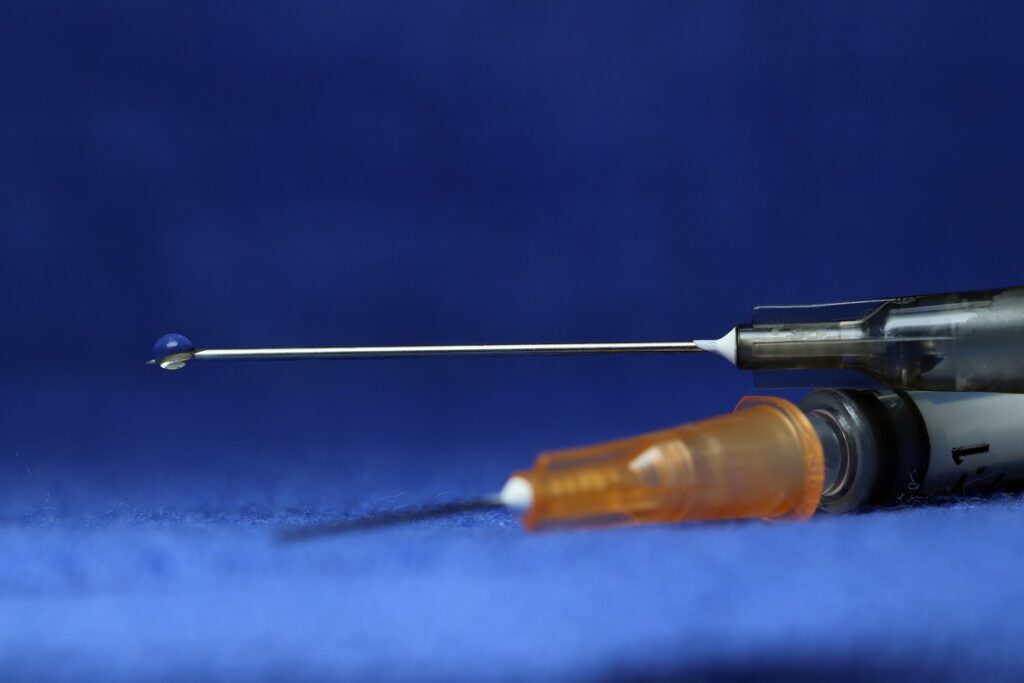

In February 2020, United Nations Secretary General António Guterres visited Pakistan to initiate the country’s annual nationwide polio campaign. There, he met with frontline workers from the Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme, a team of 260,000 polio vaccinators who travel door-to-door to ensure as many children are protected as possible. The UN Children’s Fund, supports the program in Pakistan and helps to procure and distribute over 1 billion doses of polio vaccines worldwide annually.

In Afghanistan, public health officials have responded to outbreaks of wild poliovirus with similar efforts. Yet, limited vaccination resources, compiled with inaccessibility in the Southern Region of Afghanistan, has led to potential populations of virus-susceptible children. To address this issue, the Polio International Health Regulations Emergency Committee led by the WHO convened on June 23 2020 to discuss progress and challenges in ending the transmission of poliovirus in Afghanistan and Pakistan. According to the committee, the international spread of the virus from these two countries still remains a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this public health issue by disrupting polio surveillance and immunization efforts. This could lead to the rapid emergence of vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) strains which create additional risks for infected communities; the implications of cVDPV are still not fully understood. The vaccine-derived poliovirus is a strain of the weakened poliovirus that was initially included in the oral polio vaccine, which has changed over time to behave in similar manners to the wild poliovirus. Although cVDPV is rare, it can occur in non-immunized or under-immunized populations. When routine supplementary immunization activities are poorly conducted, a population may be susceptible to both the vaccine-derived poliovirus, as well as the wild poliovirus.

The oral polio vaccine is often used in lower income countries because it is cheaper and easier to administer than the Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV). If a population is adequately immunized with polio vaccines, it should be protected from both the wild poliovirus and the vaccine-derived poliovirus. However, cases of cVDPV have appeared in places with poor sanitation and large numbers of unvaccinated children. In these instances, the virus can mutate, and in rare cases, advance to the point of causing paralysis in its victims. Yet, the risk of contracting cVDPV is still minimal when compared to the public health benefits of immunization. Over 10 million poliovirus cases have been prevented since mass vaccination began. Cumulative efforts among governments, health organizations, and national campaigns have been incredibly effective, with 86% of infants worldwide receiving three doses of the polio vaccine in 2019.

The African continent has now gone three years without a case of wild poliovirus. However, 16 African countries are still experiencing cases of the vaccine-derived poliovirus. One of these countries is Nigeria, the last country in Africa to experience cases of the wild poliovirus. The threat of poliovirus reemergence in Africa is more prominent during the COVID-19 era, as the current pandemic has disrupted polio immunization efforts. In April, the WHO and its partners recommended a temporary halt to vaccination efforts in Africa as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving the continent vulnerable to a potential polio scare. To eradicate the virus entirely, over 90% of children would need to be vaccinated. The question now is how to prevent poliovirus from reemerging in some countries and spreading in others, especially amid a world health crisis.

The next step for health organizations fighting poliomyelitis is to ensure that the African continent maintains its wild polio-free status. Efforts to continue immunization can help shield the continent from cases of wild polio spreading from Afghanistan or Pakistan, the only two regions in the world where the virus remains in circulation, thereby ensuring the health and safety of African children and communities.

Despite the remaining challenges with the vaccine-derived poliovirus, the eradication of wild polio is something to celebrate. A century ago, the world was shocked by this terrifying disease and had little to no understanding of how to stop it. Now, the scientific community understands how the poliovirus works and, more importantly, how to eradicate it.

While global eradication of wild polio has yet to be achieved, collective work among governments, NGOs and communities can lead to tremendous progress. And, perhaps the fight against polio can provide insight on how the international community can face the daunting public health challenges that lie ahead.