There is severe underreporting of the ongoing violence in Chad and its surrounding countries. While mainstream news sources fail to detail the immense destruction, poverty, hunger and human rights violations taking place in the Central African country, Chadians continue to live in some of the world’s worst conditions. On the 2019 Human Development Index, Chad ranked 187 out of 189 countries. Today, 66.2% of Chadians live in severe poverty, 3.7 million people are food insecure and 2.2 million people are malnourished. While climate change and other external threats continue to exacerbate Chad’s resource scarcity, violence is the most significant strain on the country’s ability to provide for its citizens’ basic needs.

For context, immense violence since the early 2000s has caused a massive refugee problem, with thousands of Chadians seeking refuge in the eastern and southern parts of the country, with some even fleeing to neighboring countries. The 2019 Humanitarian Response Plan reported that, “4.3 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, of whom only 2 million are targeted with adequate support.”

In order to combat these issues, the UN Security Council ratified Resolution 1778 on September 25, 2007, in collaboration with Chad and the Central African Republic, which created the UN Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT). According to the United States Institute of Peace, MINURCAT’s mission was to “help create the security conditions conducive to a voluntary, secure and sustainable return of refugees and displaced persons… by contributing to the protection of refugees.” Along with MINURCAT, which deployed its own troops, the international community stationed UN police operations and the EU’s military force (EUFOR) in the country. The UN understood that these operations were necessary to “promote human rights and the rule of law, and promote regional peace.”

In the late 2000s, MINURCAT began making positive strides. An Amnesty International report found that “attacks on humanitarian workers and civilians, which reached alarming levels in the last months of 2009, have begun to decrease as MINURCAT soldiers have been able to carry out patrols in sensitive areas they were previously unable to patrol.”

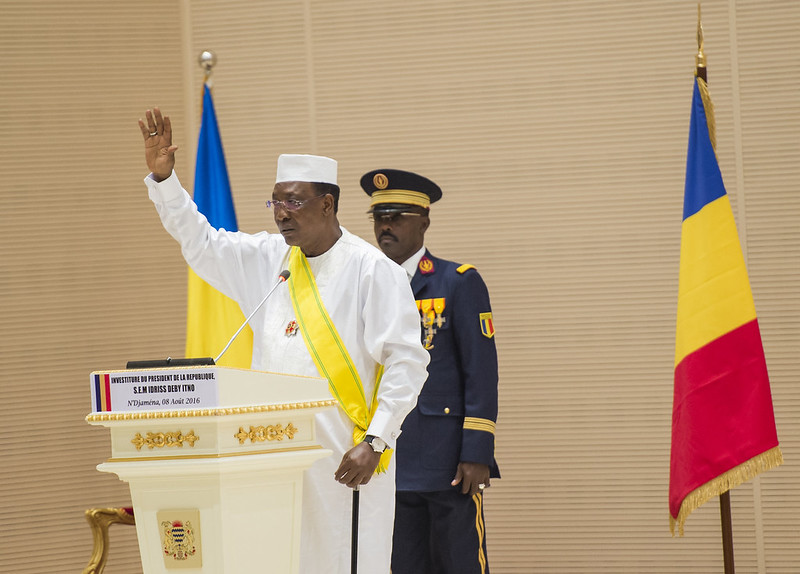

Despite substantial progress in this dire humanitarian and security situation, Chadian President Idriss Déby began leading the movement in 2010 to get rid of MINURCAT, requesting that MINURCAT leave the country and suspend all operations.

Notably, President Déby has a history of repressing citizens. According to an Amnesty International report in 2013, President Déby was accused of suppressing “critics of his rule, and of ignoring promises to respect human rights when he came to power in 1990”. His intentions for wanting to remove MINURCAT from Chad are questionable.

President Déby claimed that he wanted to protect national sovereignty and insisted that MINURCAT was not truly helping Chadian citizens. He was explicitly critical of MINURCAT troops as they were not “fully deployed.” On January 15, 2010, the Chadian government notified the UN Secretary-General, in an informal note, that Chad wanted MINURCAT to withdraw its operations in Chad by March 15, 2010. The final terms of the agreement allowed MINURCAT to stay in Chad until the end of 2010.

Following the departure of MINURCAT, President Déby began working to protect his citizens solely through his own police forces. However, as Susannah Sirkin, deputy director for the group Physicians for Human Rights, stated in May 2010, it is crucial that MINURCAT remain in Chad. In her words: “The security provided by MINURCAT is absolutely essential. There is almost no judicial system there, very weak police force. There are not female officers to deal with the really rampant sexual and gender based violence on the border and in the camps.” She also stated that there was no demonstration that “…there would be any kind of adequate replacement for this protection.”

Additionally, Sirkin reflected on the importance of MINURCAT – securing food, water, sanitation, and health care for 250,000 Sudanese refugees and 150,000 Chadians that were uprooted due to violence on the Chad-Sudan border. MINURCAT was able to help provide these essentials as the operation “provided military escorts…” to where the humanitarian groups were stationed. This protection was vital as criminals tend to target humanitarian groups. Furthermore, Sirkin mentioned that “[t]here are crimes, including violent crimes committed even by Chadian camp personnel.” This makes it even more necessary that an independent force like MINURCAT remains in Chad.

To no surprise, President Déby’s attempts to ensure safety for his citizens have failed as violence and food insecurity has worsened. In addition to general violence, Chad’s violence problem has worsened due to violent extremist group Boko Haram. Boko Haram is a terrorist organization in the Sahel region that claimed responsibility for the suicide attacks in N’Djamena, Chad’s capital, in 2015 that took the lives of at least 27 people. The Institute for Economics and Peaces’ New Global Terrorism Index recorded that in 2014, Boko Haram killed 6,644 people in many attacks throughout Nigeria, Chad, and Cameroon. This escalated violence has also caused a dramatic increase in hunger and malnutrition. In 2009, when the MINURCAT operation was active in Chad, approximately 4.5 million people were undernourished, whereas in 2019, approximately 6.1 million people were undernourished. The increased chaos in Chad today makes the need for an operation like MINURCAT even more necessary.

It is clear that unless President Déby improves his relationship with the UN, instability in Chad will worsen.