This piece is the first installation of a two-part series on the Chinese One Belt, One Road strategy. To read the second installation, click here.

(Personal photograph)

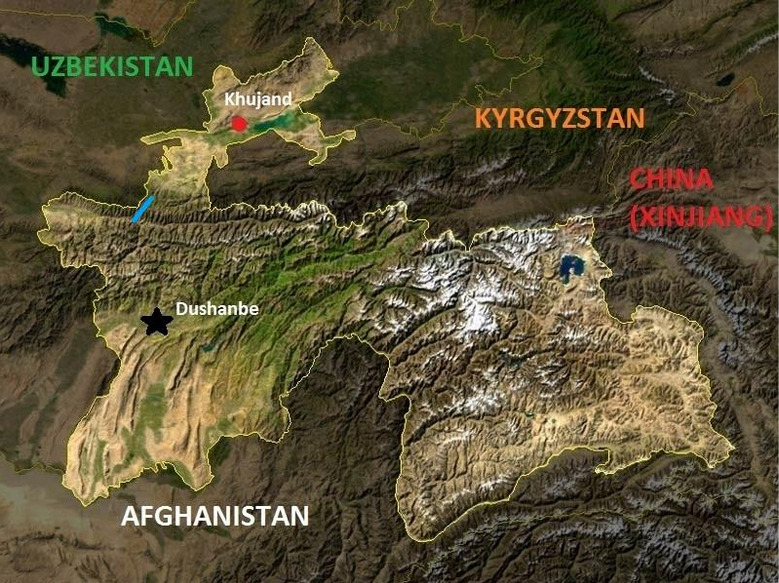

When I arrived in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, a landlocked, mountainous country in Central Asia and the smallest and poorest in the region, I was prepared for the ubiquity of Russia’s regional influence. Our advisors from the Critical Language Scholarship program in Persian warned us that Tajiki Persian, unlike the Iranian Persian we were accustomed to learning, had been heavily influenced by Russian, even adopting the Cyrillic alphabet after usage of the traditional Arabic script was abolished. Due to Soviet governance in Tajikistan, which only ended in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union, most Tajiks had at least some Russian proficiency, and Russian is still viewed as an important lingua franca. Indeed, upon arriving, I quickly became jealous of my classmates who could speak Russian; when their Persian failed them, they could still easily communicate with most of the locals.

What I was less prepared for was just how much influence China had gained in the country. I knew that China was making significant inroads into Central Asia under a strategy known as the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), but I never expected the pervasiveness of Chinese brands and products, the Chinese characters emblazoning nearly every piece of heavy construction machinery and the Tajik-Chinese Friendship Buses occasionally running up and down Rudaki Avenue, the main street of Dushanbe. Most of all, I had no idea just how many Chinese people and firms were working in Tajikistan, an oft-forgotten part of the world. Indeed, the wide extent of Chinese penetration in Russia’s historical backyard was enough to leave me a little stunned, a true testament to one of the hidden successes of Chinese foreign policy.

“There are a lot of Chinese here,” almost every Chinese person tells me. I found myself swiping pictures of construction projects on a phone, the manager saying, “These are all the projects I’ve worked on in my time here.”

“This is in Dushanbe?” I asked.

“No, this one is near Kulob.”

Kulob is a relatively major city to the south of Tajikistan, four hours away by car from Dushanbe on a good day, nestled in the rolling golden hills of the Khatlon region. The Chinese have projects all around the country, even in the remote and forbiddingly mountainous Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province (GBAO). This is an area noted for recent violence between government forces and rebels in 2012 and for its record of supporting separatism during the Tajik Civil war. It was only after this conversation that I realized just how strong the Chinese presence in Central Asia was.

(Bertramz/Wikimedia Commons)

News outlets covering Tajikistan and Central Asia are few and often riddled with skewed, if not outright erroneous, information. An outbreak of violence in Dushanbe on September 4, 2015 was blamed on Islamic militants by many Western outlets, despite insufficient evidence and reasonable cause to suspect other motivations. Far from the Islamic frenzy many Western pundits were eager to point to, the incident was really a politically-motivated rebel group led by a former minister fighting against the central government.

It should have come as no surprise then why I had initially underestimated China’s presence in Tajikistan and much of Central Asia. Despite relative interest in China’s Silk Road Economic Belt, few Western outlets seem invested in or capable of reporting on China’s expanding ties with the region, and what the One Belt, One Road strategy (OBOR) and SREB means for China’s foreign policy.

The OBOR strategy is a development framework proposed by China, invoking the storied historical Silk Road in order to encourage regional integration and economic development so that Eurasia once again becomes a coherent region with stable and integrated economies. The OBOR strategy encompasses both a land-based SREB and a Maritime Silk Road, which aims to foster positive relations with Indian Ocean states and secure shipping and transportation lines in the Indian Ocean.

For China, this push into Central Asia is a multi-pronged project, attacking many goals at once. For one, it is a ploy to expand elsewhere in light of the American “Pivot to Asia”, which threatens to check Chinese ambitions in the Pacific. Central Asia is also rich in natural resources, in particular natural gas in Turkmenistan and oil in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, making it a region of interest for Chinese energy extraction. Even if Tajikistan is not rich in high-demand natural resources itself (although it does boast large reserves of aluminum and coal), its location makes it a vital lynchpin in China’s Central Asian plans.

The move also has a domestic angle, as China seeks to assuage ethnic tensions between the Uyghurs and the Han Chinese in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China’s expansive desert province in the Northwest. Tensions have resulted in riots and incidents of terrorism, generally stemming from the Uyghur’s frustration with denial of opportunity, as provincial economic growth benefits mostly incoming Han migrants to the province. Through development and expansion of economic opportunity, China seeks to turn the provincial capital Urumqi into an economic hub for the greater Central Asian region. This integration would not only stimulate China’s own economy through healthier trade ties, but also promote region-wide stability that would help bring order to Xinjiang, allowing China to manage its terrorism concerns.

For Tajikistan, this means expansion of already strong Chinese economic ties, welcome in a country where remittances – money sent home from work abroad – make up over half of the national GDP. Already Tajikistan relies heavily on Chinese manufacturers and capital for everything from basic necessities to road repair and construction; 45% of Tajik imports are from China, and while China is the destination for only 11% of Tajik exports, total trade volume approaches $1.8 billion, making China one of Tajikistan’s largest trading partners.

The Chinese in Tajikistan are predictably praised for their prowess in infrastructure, having become important partners in numerous construction projects. The Shahriston Tunnel is China’s crowning achievement: bypassing hours of dirt one-lane mountain roads linking Dushanbe with the northern Sughd region, including the major city Khujand. It is especially valuable in the winter, when the dirt roads become dangerous and transportation becomes exceedingly difficult, if not impossible.

(Poulpy: based on the work of NASA, edited by Author/Wikimedia Commons)

Of the three dominant powers in Central Asia, China is the clear frontrunner in the region’s developmental economic sphere, enjoying “unassailable economic supremacy”. As the Russian economy wanes, Central Asians are becoming all too aware of the dangers of reliance on Russia, especially remittance-dependent Tajikistan, where most Tajik males must go to Russia to find work. The US has found itself in a quagmire in Afghanistan, and shows little attention to the region due to its focus on the Middle East and the Pacific, leading to misinformed decision-makers and a lack of coherent strategy. This leaves China, an active participant in the development and stability of the region for a decade, constructing much needed roads and supplying copious volumes of investment and capital.

Russia still leads Central Asia in many ways. Teenagers blast Russian music and serenade their hopeful dates in Russian, indicating Russia’s sharp edge in soft power. Russian language is still a necessity, given that most Tajik men are forced to search for work in Russia or Kazakhstan. Russia is also the main security provider of the region; when the Tajik government struggled with the rogue minister in early September, it turned to Russia rather than China for security aid and cooperation.

Yet here I continue to experience China’s ever expanding influence. I often see literal truckloads of Chinese workers, and run across them everywhere, from Rudaki Avenue to villages far off the beaten path. Tajiks say “nihou” (unable to correctly pronounce the sound “ao”) even to non-Chinese people. Nobody casts a second glance at the Chinese characters on their packets, boxes or machinery. Even working for a Chinese firm seem to be a point of pride for some Tajiks eager to tell me about their place of occupation. Passing by the Chinese Embassy on my way back home, I once saw a long list of Tajik students who had been granted full scholarships to study all across China for their undergraduate education.

All of these examples point to China’s rapid accumulation of influence in a region where it had little, if any presence twenty years ago. In that time, it has not only left its mark on Tajik development, but has also won the hearts of Tajiks, amazed at China’s growth trajectory and its perceived no-strings-attached approach to international development (as opposed to Western methods of intervention and structural adjustment in exchange for aid, epitomized by IMF and World Bank policies). In a fast-paced theater famous for games of spies and intrigue, China stands poised to surge in regional influence if other powers are not able to formulate better regional strategies.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.