This article is the second of a two-part series on the aftermath of Scotland’s referendum on independence. Please visit the first article, “A Hard Break: Scotland’s Struggle,” by Abigail Becker

“It’s all for nothing if you don’t have freedom.”

-Mel Gibson as William Wallace, Braveheart

In one of the most historically inaccurate films of all time, director and lead actor Mel Gibson managed to get one thing about Scotland’s relationship with the UK right, particularly when it comes to increasing Scottish influence in the international community: without freedom, those efforts are mostly in vain.

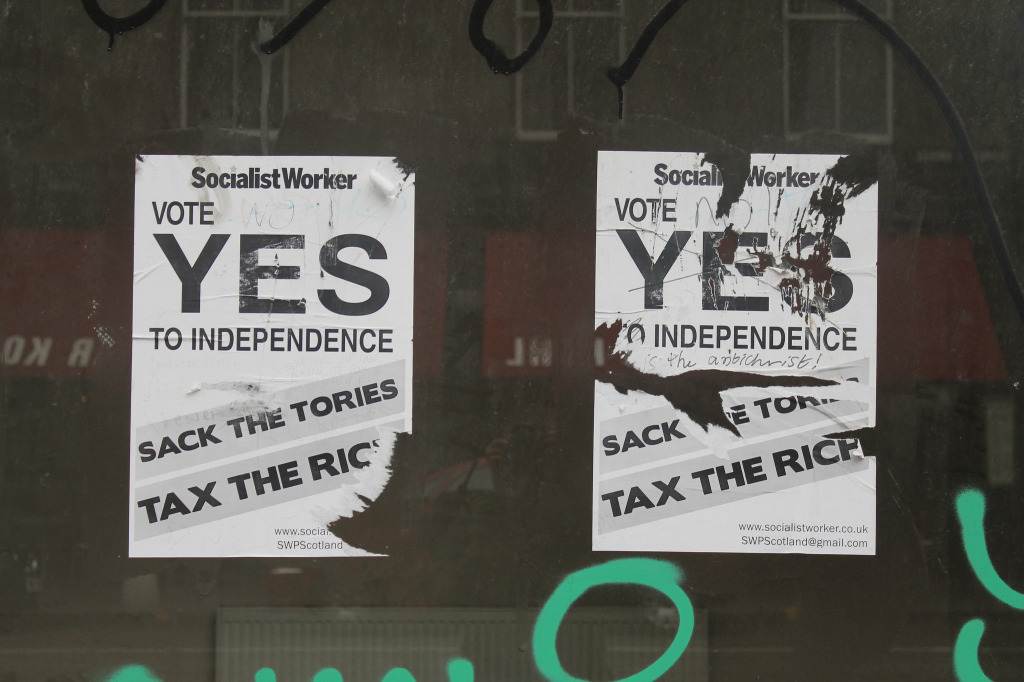

The politics of the Scottish independence referendum reveal a populace more interested in domestic economic advantage than foreign influence. Notwithstanding, independence from the United Kingdom is a necessary prerequisite for Scotland furthering her international interests. In “The Ties That Bind: Towards a Greater Scottish Role in Europe and the Regions,” Alexander Beck takes a somewhat different perspective, arguing that Scotland, a region with a cohesive national identity, can reform its relationship with the United Kingdom to further both its international prestige and influence.

While Beck offers a comprehensive discussion of regional politics in the European Union and the history of Scotland’s relationship with the UK, his discussion begs the question: what do the people of Scotland actually want, and what is the best way for them to get it?

On September 8th, 2014, Scotland voted by a 55-45 margin to remain in the United Kingdom. If American political veteran and campaign consultant James Carville were around, he might have summed up the election as follows: “it’s the economy, stupid.”

Scotland has a bigger GDP than France and Germany when including oil and gas consumption. The Financial Times even noted that Scotland could have been more financially salient than the UK had it become independent. One article for The Guardian, which even borrowed Carville’s quote for the headline, said the economy outstripped all other issues in popularity, giving significant credence to the argument that a discussion of regional influence will likely take a back seat in the coming years.

A BBC poll asked Scots to rank their priorities. Unsurprisingly, the economy was number one. While Scotland and the UK’s relationship was number four, that dynamic is much different from the issue of Scotland’s relationship with the rest of the world, which didn’t even make the list. The Guardian also cited another, more detailed poll, which showed the issues most important to Scottish voters were the economy (30%), healthcare (11%), and pensions/benefits (10%).

Ironically, Beck’s priorities for Scotland mirror closely the priorities of Scottish politicians, despite public polling evidence to the contrary. According to Thomas Hunter, a millionaire businessman and philanthropist who has extensive work in the region, “Only 3% and 2% of those polled respectively said EU membership or currency was most important to them in deciding how to vote in the referendum yet our politicians see these issues as priorities.”

James Knightley, a senior expert at ING in international economics began from the premise of local control, arguing that returning critical economic drivers like tax and welfare reform will create a more equitable society. Left unanswered, though, is how a society that doesn’t even set its own taxes or have an immigration policy be a significant power in the EU without meeting these basic requirements.

The answer? Scotland can’t become a significant power without independence. The real question then is twofold: is independence a more suitable alternative to Beck’s vision for Scotland, and will Beck’s recommendations and/or independence ever lead to Scotland having greater international influence?

At the outset, it should be noted that Scottish are even more divided on foreign affairs than they are on domestic affairs. For example, it was only in 2012 that the Scottish National Party ceased opposition to Scottish membership in NATO. After a close and intense debate, two higher ups in leader Alex Salmond’s Scottish National Party (who controls the parliament) resigned in protest.

While membership with the UK may be beneficial for Scotland, such benefits ignore the opportunity cost of becoming independent. Ultimately, a post-independence currency union and security partnership with NATO would resolve most of these issues, which were also dispelled in 2007 as scare tactics by now-Prime Minister David Cameron.

“Supporters of independence will always be able to cite examples of small, independent and thriving economies across Europe such as Finland, Switzerland and Norway,” Cameron said. “It would be wrong to suggest that Scotland could not be another such successful, independent country.”

Beck’s argument that Scotland’s ties to the UK bring it influence through the UK’s magnitude is perhaps the paper’s strongest moment, but fails to pass the “independence would be better” test.

First, even Beck acknowledges instances where the UK ignored or misled Scottish officials seeking to participate, and unduly forced its influence on nuclear power upon Scotland. This is corroborated by the UK’s forcing of Scotland to be a base for the Trident Missile System, which has remained a sticking point in the relationship. As long as micro-issues continue to plague the relationship, increased cooperation will remain tenuous. Second, according to a professor of European Law at Oxford, Scotland’s EU membership “should be assured” [1] following potential independence. This would also cement Scotland’s place in the Council of Ministers, a much simpler path to that seat than Becks’ proposal to lobby for a change to the Lisbon Treaty.

Third, an SNP white paper suggested opening 100 embassies if independence happened, a significant step in the direction of establishing influence. Nicola Sturgeon, the Deputy First Minister, said this presence would increase Scotland’s diplomatic footprint: “Our presence would be, in terms of physical presence on the ground, comparable to other small independent countries,” she said.

The last question that must be asked is, at its most influential, what could Scotland do? A discussion of niche diplomacy, the idea that smaller nations select niche issues to publicize and affect, is useful for context. Scotland would likely be a middle power, and likely find success in the international arena following Canada’s campaign to ban land mines or protect the ozone layer, or Norway’s campaign for world peace. As the world’s hard powers remain focused on high politics security issues, Scotland’s ties to the UK will be irrelevant in influencing broader geopolitics, so a complete break might also offer Scotland greater mobility to push its personal agenda.

Scotland is anomalous in Europe in that it is region that also maintains a unique culture, but that unique culture and autonomy has stayed for 307 years too long. If Mel Gibson were to rewrite one of Wallace’s more famous quotes, perhaps would conclude something like this: “Scotland has rope burn, and the ties that bind aren’t worth retying, they’re worth cutting. FREEDOM!”

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.

Other Works Cited

[1] Sionaidh Douglas-Scott, “Will Scotland Be in The European Union?” Yes Scotland, ltd., n.d.