During the election, no one on the political Left engaged in the mental exercise of visualizing an America with a President Trump. It was an absurd, unimaginable scenario, not to mention a terrifying one—some have since taken Trump’s election as evidence that we are living in a simulation gone haywire. Day after day in the wake of Clinton’s defeat, liberals have been forced to accept a reality that contradicts all of their assumptions about American politics, values and social norms—the fiber of the nation. However, most attempts to explain Trump’s victory shift the blame outwards: the Left blames Middle America, the GOP, occasionally each other, but rarely themselves.

Though solidarity within the party is crucial at this point, Trump’s presidency should have cued an identity crisis and some long-needed soul-searching. The left needs to rethink its language, reconstruct its image and embrace new electoral strategies. But as of now, despite the ubiquity of the “Democrats have lost touch with the working poor” narrative, the Party has made no coordinated push for internal reform. Underlying divisions roughly along the Hillary-Bernie split continue to fracture the party even as the Democrats unite against Trump. Echoing this opposition, the liberal media speaks in one voice: a self-righteous one that either loudly berates or snidely raises its eyebrows at Trump’s every move.

While it is tempting and easy to rally around a shared disdain for the new president, it will take much more for the Democratic Party to pull off a sustained comeback in American politics. As the last election revealed, adherence to the status quo is now out of the question. It’s very possible that we are living through a monumental shift in the political party system on par with that of 1932 or 1968, and Democrats must react and adapt. This does not mean abandoning the best of liberal values. On the contrary, these must now be framed in a new light to fight Trump’s faux-populism with policy proposals that would actually benefit most Americans, like preserving universal health care. On the contrary—a Democratic electoral comeback will take a complete image overhaul, accomplished by a change in language and – crucially – in spokespeople.

Unfortunately, it seems that the Party has yet to recognize this need in the midst of the post-election noise. According to newly reelected Senate Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, the Democrats don’t need change. “I don’t think people want a new direction,” Pelosi told CBS. “Our values unify us and our values are about supporting America’s working families.” Be that as it may, establishment Democrats like Pelosi apparently cannot see the growing alienation of America’s working families from the Party. If not new values, the Party desperately needs to learn to communicate its commitment to all Americans in an age of rising insecurity in almost every area of life. There is a deeply unsettling irony in a billionaire businessman chosen to champion the needs of the working-class American; it shows how broken and delusional the Democratic Party has become about its perception among voters.

The rise and fall of the Third Way

To understand how we got to the twilight of the liberal era, we can look to its dawn. The historical and ideological underpinnings of the modern center-Left date back to Tony Blair’s “Third Way,” a label for “the new politics which the progressive centre-left [was]forging in Britain and beyond” at the turn of the century. A 1998 political manifesto of the same name aimed to reconcile traditional liberalism with social democratic progressivism, two political strains that had existed in opposition to each other thus far. The Third Way claimed there was no insurmountable incompatibility between these ideologies, and that values like “patriotism and internationalism, rights and responsibilities, the promotion of enterprise and the attack on poverty and discrimination” could all be pursued on one platform. With that utopian claim, modern liberalism was born.

The Third Way purported to be a modern outlook that used technical expertise and empirical proof to pursue policy that “works.” Practically, however, it became the platform and rallying cry of a new political and social class, a sign of a capitalist, neoliberal, globalizing Western order slowly stretching its tendrils across the globe. Days after delivering his speech unveiling the Third Way, Blair met with US President Clinton and other Western leaders to launch this new center-left ideology across the West.

Though its birth was grounded in the political realities of the day, the Third Way came to transcend its original purpose—to prop up recent electoral success of British Labour, and similar parties across the West, with an explicit ideological framework. Over the next two decades, the Third Way remained the foundational logic of the mainstream political Left. Blair’s brand of progressivism—cool, vague, globalizing, pro-business, pro-financial sector—has had its fair share of devoted and powerful adherents across the pond: both Clintons and even Obama, if we look at his policy and not his populist image.

Though dominant, the Third Way still faced criticism within the Left. Voicing far-left skepticism, political journalist Luke Savage characterizes the Third Way as “a hostile takeover of the center-left by a new generation of center-right technocrats whose main achievement was welding a refurbished lexicon of liberal progressivism to the processes already initiated by the likes of Thatcher and Reagan.” Here Savage goes beyond the typical far-left critique of the center-left for being too moderate. He characterizes the Third Way as a usurpation of left-wing politics by conservatives (neoliberals) who have learned to speak the Left’s language, an insidious attack on traditional left-wing populism made virulent by its very lack of overt hostility.

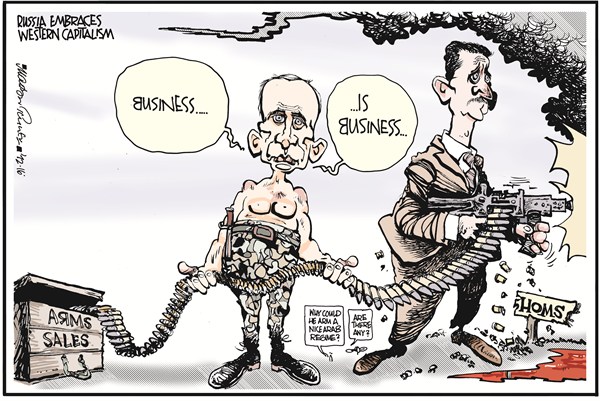

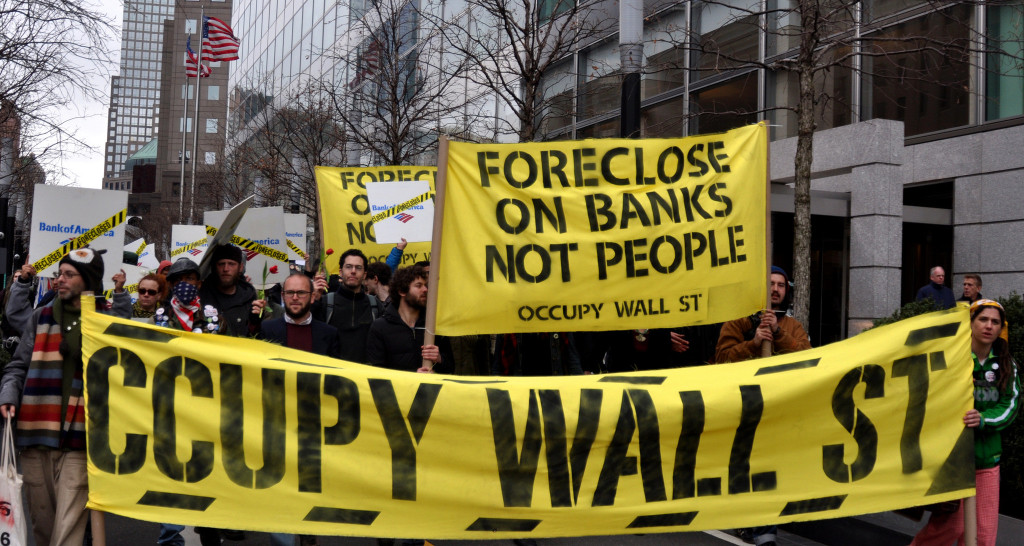

This is far more dangerous because it eliminates any true leftist option in a two-party political system. Today, the far-left voice in American politics is largely delegitimized, its only outlet ‘radical’ movements like Occupy Wall Street that even most Democrats roll their eyes at. In the last election, we saw this situation reach its boiling point with Sanders’ unprecedented success. However, the Democrats failed to take seriously enough the anti-establishment sentiment sweeping across the nation and dismissed Bernie as abrasive and unelectable.

As Hillary’s humiliating defeat shows, it’s time to bury the Third Way once and for all and reembrace leftist populism.

How did he win?

While leftists critiqued Clintonite policy for pandering to elite, technocratic class interests, right-wingers object as much to the liberal aesthetic as the policy itself. The conservative stereotype of the liberal, related but distinct from left-wing policy, played a major role in the last election. It revealed the extent of the rising backlash against the neoliberal persona, which Clinton typifies.

Despite Clinton’s pro-working class rhetoric and policy proposals, the working class preferred Trump for his political incorrectness and his ability to voice “true but unpopular things,” in the words of one voter. The irony of a billionaire elected on populist terms is deep—it speaks to the extent of the working Americans’ distrust for the modern Democratic establishment, controlled by a class of liberal technocrats. In the words of one Trump supporter, “Hillary Clinton represents everything that is wrong in government.”

For this reason, even her moderate, inclusive policy stances, which should have appealed to a wide range of voters including the working classes, did little to bolster her image. On the contrary, her inability to break political correctness probably contributed to her disingenuous image, while Trump became the candidate who told it like it is. In fact, even Clinton’s own supporters cited her “dishonesty/secrecy” as their top concern in a September PEW poll. Trump, on the other hand, owed his support mainly to the fact that “he is not Clinton,” closely followed by his status as a “political outsider” tied to his perceived ability to “bring change.”

Trump’s victory suggests that voters are more frustrated with the political elite than the economic. Wealth in itself is not distasteful to American voters; this is a country founded by Puritans who believed that God chose his favorites and made them rich. To this day, the mythos of the American Dream remains powerful despite evidence that upward mobility grows harder each year—in Fox’s 2017 American Dream poll, only 15% of respondents felt the Dream was “out of reach”. Despite (or because of) Trump’s personal and professional flaws, many voters believed a business-savvy political outsider to be more trustworthy than a career politician. After all, political dynasties like the Clintons are the closest thing the US has to an aristocratic class – and America was born from a distrust of aristocracy. Tapping into the prevalent strain of thought, Trump branded himself as a self-made man, the quintessential aspirational figure in the American imagination.

What now?

It would be complicated to analyze all the ways in which Americans didn’t trust Hillary, but the lesson for the Democrats is rather simple. To attract votes, the Party should distance itself from establishment figures and politics. This will not require drastic departure from the core of the party platform: economic security and prosperity for the working classes; environmentalism; equality and justice for all genders, races and sexual orientations; expanding access to healthcare and orientation. These are all common goals of most voters, at least among those who would ever consider voting Democratic. A subtler shift is in order.

The way forward: politics

To begin, the Democrats should position themselves against the status quo of Wall Street, campaign finance and big business, and make it clear that the party stands for total overhaul and increased transparency and regulation. The most obvious way to do this is simply by choosing more candidates with more appropriate records. That is to say, candidates less like Clinton and more like Elizabeth Warren, whose no-nonsense rhetorical style and “critique of an economic system she says is rigged against the little guy” make progressives squirm with excitement at rumors of a 2020 presidential bid. One of the easiest lessons of the last election was that politics today is all about personality (voters’ top reason for picking their candidate on both sides was simply that they were not the other, and top concerns about each candidate also centered on personality, not policy).

In addition, it is time to stop clinging to free trade as an ideal unto itself. Opposition to secret trade agreements like the TPP and TTIP loomed large in this election, calling into doubt the sacred neoliberal dogma of economic openness as a panacea for all social and economic problems. As of October, while scholars and academics still overwhelmingly favored increased involvement in the global economy, among the general public most opposed free trade on the grounds that it “lowers wages and costs jobs in the US.” Regardless of the technical accuracy of this view, it is clear that free trade has its costs, and the Democrats must find a meaningful way to speak to these issues. In the words of British writer and activist George Monbiot, “anyone that forgets that striking them [secret free trade agreements]down was one of Donald Trump’s main promises will fail to understand why people were prepared to risk so much in electing him.” If there is one area where Democrats can learn from Trump, it is adopting a more emphatically pro-American economic stance in their rhetoric.

Today’s most important, divisive issue remains immigration. Discussion around it has become a minefield of emotion, values, assumptions and accusations. As soon as talk turns to immigration, liberals tend to immediately make the conversation personal, relying on a mixture of emotional appeal and implied moral superiority. On the other side, conservatives go straight to national security, falling wages and violent extremists. As such, the dialogue on both sides surrounding immigration is reductionist, hostile and self-righteous. Facts only enter the equation when they conveniently prop up a priori values—conservatives like to ignore all instances of homegrown (often, white racist) terrorism and refuse to consider arguments that the so-called “Muslim Ban” could actually fuel anti-US sentiment; liberals plug their ears at the first mention any immigration reform, conveniently forgetting that President Obama deported more people than any other president.

Moving forward, the Democratic Party should hold true to its pro-immigration stance but infuse its rhetoric with more nuance and intelligence. Instead of relying on clichés like “America was founded on immigration,” etc., they must provide stronger counterarguments to false narratives of immigration hurting the economy and threatening national security. Furthermore, the Democrats wrongly dismiss all anti-immigration sentiment as ignorant and racist. Yes, purely racist arguments do not deserve valid consideration, but genuine fears about safety and economic insecurity should be addressed, not ignored. Too often, liberals refuse to engage with anti-immigration arguments, which is extremely counterproductive.

The way forward: language, image & attitude

This brings us to the largest public relations challenge facing the American Left, one much more nuanced, emotionally charged and difficult to overcome than policy direction. It has to do with language, perception and values. Increasingly, liberals are viewed as intolerant, hypocritically championing abstract values of equality while maintaining an air of moral and intellectual superiority over anyone who questions their logic. This has been the main complaint voiced by Trump voters in the wake of the election, creating “animosity in otherwise pleasant conversations” between liberals and conservatives, as blogger Sam Altman described.

After the election, Altman interviewed Trump voters across the country to try to understand their point of view, and found many feeling “silenced and demonized” by the liberal establishment and its representatives, be it the Democratic Party, coastal media channels or other citizens. If Democrats want to win over supporters, not alienate potential ones, it must find a way to relate to Trump supporters, not call them “Nazis, KKK, white supremacists, fascists, etc.” If this conflation weren’t offensive enough, the very term ‘Trump supporter’ has become a quasi-slur in liberal circles. As one Trump voter pointed out, “we have mostly the same goals, and different opinions about how to get there.” To do so, it is as difficult as it is crucial to set aside aesthetic objections to Trump and focus on concrete policy. Pointing out Trump’s racism and sexist over and over again has clearly gotten liberals nowhere—this just perpetuates an exhausting media echo chamber that drowns out more intelligent analysis.

Unfortunately, after an extremely divisive election, there has been nearly no effort to heal divisions, understand the views of the other side and emphasize commonalities. Social media trends like #notmypresident only divide the country further between two warring camps. The same is true of the deluge of righteous ‘look what Trump did now’ coverage of the regime’s every move and Trump’s every tweet. For example, liberal media coverage of Trump’s first speech to Congress ranged from incredulous to panicky; the general consensus being that it “gave his nightmarish agenda a newly ‘presidential’ gloss” and “we should be worried.” But, as the same article conceded, many would have “tuned in and simply heard a promise to provide unemployed and underemployed Americans with the jobs they sorely needed.” This is a point of view rarely emphasized in media coverage. Perhaps the worst of the media response is headlines like “It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses” that characterize the country’s division as “the sane vs. the mindlessly angry.” Though of course we should avoid drawing an overly simplistic conflation between the Democratic Party and the ‘liberal media,’ mainstream, left-leaning media sources tend to report from the center-left, and thus generally capture the elite liberal response to the Trump administration’s policy.

In general, liberals have responded with moral outrage over the regime’s policy and an aesthetic aversion to Trump supporters, voiced loudly by celebrities across elite industries like fashion and entertainment. These kinds of shows are only soothing to those delivering them and do nothing to convince those who agree with Trump’s politics.

It’s time to let go of the idea that society is on some unalterable trajectory of progress towards social justice, meritocracy, personal freedom, economic and societal openness and globalization. This Third Way line of thinking has fallen out of ideological vogue; nationalism, isolationism and unfortunately xenophobia are alive and well today. Trump’s election is just the latest in a string of political events reinforcing this reality. The good (and bad) news is that no future is inevitable. Presentism, the assumption that the current state of things will persist, has been disproven by history time and time again. If we learn anything from the mistaken belief that “if the West has broken down the Berlin Wall and McDonald’s opens in St. Petersburg, then history is over,” it should be that Trump’s election as President of the US does not necessarily signal the doomsday of electoral democracy and the “autocratic apocalypse.” Luckily or not, whatever is happening usually eventually stops happening, and today it is up to the Democrats to decide what is going to happen next.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.