Since the fall of Apartheid in 1994, South Africa has served as a shining example for the rest of the African continent. It is Africa’s second-largest economy, home to Africa’s best universities and the continental office of many Fortune 500 companies. For the rest of the continent, South Africa is the promised land, and each new crisis or famine brings a fresh new wave of refugees, desperate to work any job for a pittance or a bowl of food. However, despite its “Rainbow Nation” moniker, South Africa has proven to be a nation hostile to foreigners. Xenophobic attitudes run rampant throughout the population, and racially-charged outbreaks of violence have plagued the nation post-Apartheid. Brutal beatings and mob lootings happen frequently in townships where many immigrants live alongside black South Africans.

In February 2017, Nigerians living in the capital of Pretoria were targeted by angry mobs destroying their homes and businesses. The worst outbreak of violence in recent years was in May of 2008, when South Africa was rocked by a violent series of xenophobic riots that broke out across the nation. Neighbors turned against neighbors as mobs took to beating, raping, and looting en masse in the townships. By the end, 62 people were dead, dozens were raped, and more than a hundred thousand were displaced. The riots were undeniably xenophobic in nature; common phrases heard during the attacks included ‘We do not want foreigners here. They must go back to their country,’ ‘Phuma amakwerekwere, phuma!,’ ‘Foreigners must go away!,’ and ‘Go back to Zimbabwe!’ The attacks were perpetrated by poor black South Africans on not only fellow black Africans, but also Chinese and South Asians. Most victims were foreigners, but a third were South Africans who had married foreigners, refused to participate in the riots, or had the misfortune of not appearing South African enough. Racial tensions reached another boiling point in April 2015, when a wave of xenophobic violence killed seven and displaced more than five thousand. Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, condemned the violence: “(We are) witnessing hate crimes on a par with the worst that apartheid could offer.”

How did South Africa, the “Rainbow Nation,” become such a violent, xenophobic society? In Nelson Mandela’s 1994 presidential inauguration speech, Mandela proclaimed “never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another.” One of the most famous phrases in the South African Constitution is the line “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.”

After the fall of Apartheid, South Africa attracted (and continues to attract) people from all across Africa fleeing conflict or seeking to improve their fortunes – Congolese, Ethiopians, Malawians, Mozambicans, Nigerians, Somalis, and Zimbabwean, among others. Poor black South Africans, however, have come to see outsiders as threatening to their own post-Apartheid success. The promised post-Apartheid renaissance for marginalized black South Africans never arrived; instead, the government is widely perceived as having failed to address both economic crisis and mounting societal unrest.

Over the past two decades, being “South African” has become an exclusive identity; for poor blacks, their citizenship status and right to be represented by a democratic government are the only fruits of labor earned from decades of struggle, and the disillusioned citizens are increasingly seeking answers and finding scapegoats in populist, Apartheid-era ethnic solutions. South Africa has become a country where citizenship is differentiated between nationals and foreigners, and it is exclusionary, rather than inclusionary. Xenophobia, deeply entrenched in roots of South Africa from its Apartheid past, is being used as a convenient scapegoat for failed economic revitalization and has been seized upon by the disenfranchised poor masses as a form of superior social currency against “invading” foreigners.

Economic Failure

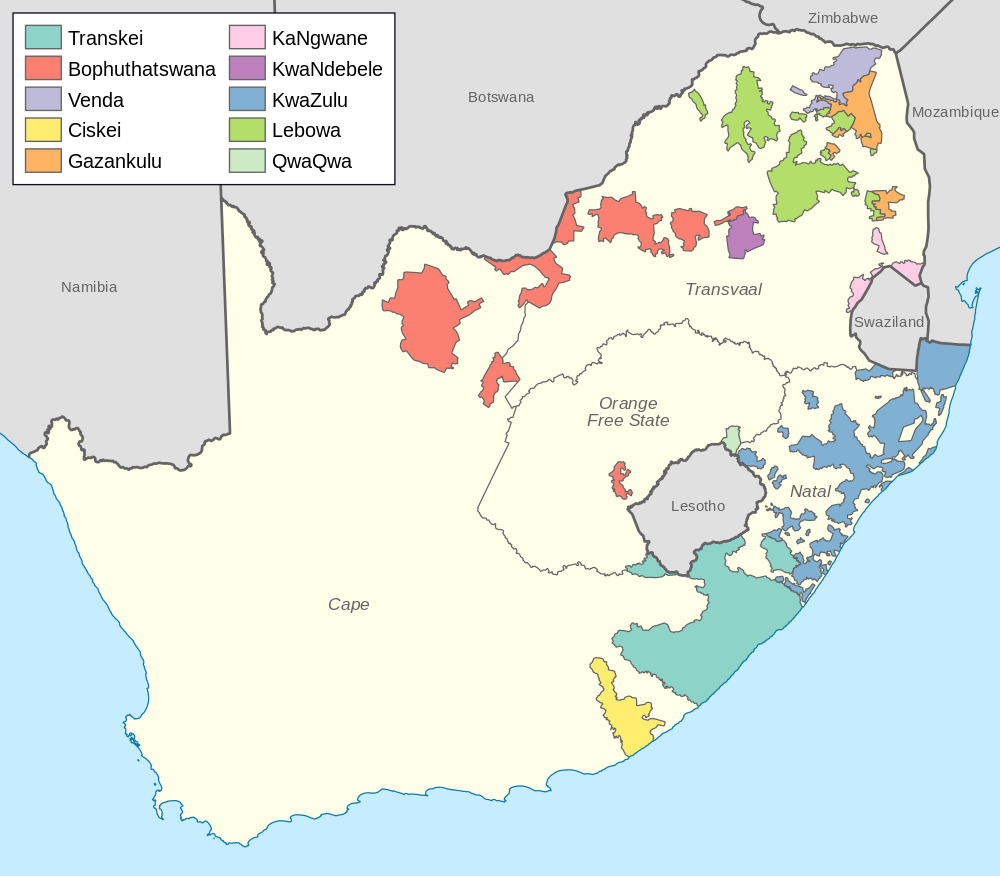

Under Apartheid, the economic opportunities and internal mobility of black South Africans were highly restricted. Blacks were deemed “foreign natives” who had to remain in their “homelands,” or bantustans. At the same time, South Africa’s booming gold, diamond, and other mining industries heavily recruited cheap migrant labour from neighboring Lesotho, Mozambique, Swaziland, Botswana and Malawi. Even before the fall of Apartheid, however, the mining industry began to decline; mining centers collapsed, jobs were lost, and fierce competition arose for the few mining jobs left. After the fall of Apartheid, the ruling African National Congress (“ANC”) unleashed a slew of initiatives aimed at empowering poor black South Africans, such as the 1994 “Building the Nation Program.”

However, South Africa has struggled to transform its economy to include its poor, low-skilled laborers: South Africa’s unemployment rates have remained relatively constant since 1998, GDP per capita has actually decreased annually since 2011, and the GINI coefficient – an indicator of economic inequality – remains one of the highest in the world. In the year leading up to the explosive May 2008 attacks, according to South Africa’s annual Development Indicators Report, the official HIV infection rate in 2007 stood at 11% of the population, the expanded unemployment figure stood at almost 38%, and 41% of the population lived on less than R367 (approximately £26) per month.

Concurrent to its economic challenges, South Africa has experienced continual increases in population size and foreign immigration which have led to a segmented labor market and ethnicized political economy. Significant push – pull factors contribute to South Africa’s linear population growth rate; push factors include the region’s continued violence, such as crisis in neighboring Zimbabwe and endemic poverty, and pull factors include South Africa’s historical and contemporary status as the regional economic powerhouse and a strong market for foreign labor. A segmented labor market has formed as these undocumented immigrants can be employed at lower wages since they do not require the benefits afforded citizens when directly competing in lower-wage sectors of the economy.

These trends have led to a highly ethnicized political economy: poor black South Africans, who have failed to see the promises of the post-Apartheid “renaissance” materialize, are angered by foreigners who they perceive to be stealing their jobs, housing, and government services and resources while they are more entitled, while wealthy South Africans – both black and white – resent “paying taxes to provide shelter and services to people seen to be pouring into South Africa to escape political incompetence and economic mismanagement further north.” Mounting frustration from poor and economic elites alike helped to not only ignite the tensions that led to the outbreak of xenophobic violence in 2008 and 2015, but also guaranteed the lack of high-level response addressing structural inefficiencies and other causes deeply rooted within the South African economy.

Social Failure

The creation of the modern South African state and South African citizenship necessitated a conceptualization of the “other,” the non-South African, which inevitably drew upon Apartheid’s legacy of racial discrimination. Apartheid, the structural coding of ethnocentrism by legally establishing the superiority of whites, led to the forceful ghettoization of racial groups and normalized racial discrimination.

Under Apartheid, the state feared that the larger the urban African proletariat, the greater the concomitant threats to the country’s political stability and industrial peace. The underlying assumption was that foreigners and human mobility were a threat to the nation’s prosperity; this perpetuated the use of geographic and cultural origins to determine utility and claims towards citizenship. Origin and race-based discrimination has continued post-Apartheid, as poor South Africans’ economic grievances against foreigners, the widening socioeconomic gap, and overall lack of upward mobility for those at the bottom has fed into a national sense of deprivation and negative discourse “othering” foreigners, or the “Makwerekere.” Poor black South Africans perceive foreigners as having unfairly exploited South Africa’s resources which undermines their own success, and this has been seized upon as the cause for the continued problems of poor black South Africans. Mobility has become a menace and a threat to the state; immigrants, thus, are now a convenient scapegoat for poor service delivery, crime, and other pathologies.

Negative discourse continues to fashion migration as a security threat. As mentioned earlier, immigration is argued to be an economic threat to prosperity; by taking away jobs, immigrants will further weaken the country’s economic potential and further burden a country struggling to reconstruct post-Apartheid. Researchers have argued that there is a cycle of antagonism and exclusion that perpetuates a lack of social inclusion: because South Africans view foreigners as threatening to their socio-economic prospects, they treat them poorly, and in turn many foreigners anticipate being treated badly by South Africans and subsequently form stronger bonds within their own networks, impeding the potential reconciliation of cultural divides. Contemporaneously, a sense of crisis – there being an overwhelming “flood” of immigrants – was introduced alongside the stereotyping of foreigners as illegal migrants, job takers, criminals and disease agents.

Institutional Failure

After the fall of Apartheid, South Africa’s new ruling African National Congress (ANC) faced a formidable laundry list of challenges. Tasked with dismantling the legacy of Apartheid and creating the equal-opportunity “Rainbow” South Africa they had campaigned on, the ANC experienced economic woes beset by political infighting which plagued productive societal discourse and reform. Overcoming decades of structural oppression and segregated systems requires a strong, unified government effort and well-developed policy planning, implementation, and strategic assessment.

Unfortunately, the South African government has failed in its task. Instead, ineffective, failed legal institutions have exacerbated xenophobic tensions and allowed for violence to act as a proxy for state sovereignty and control. The government suffers from internal schisms, poor interpretation and implementation of immigration legislation, and crippling inefficiency that hampers not only its ability to effect economic growth but its overall ability to govern and address xenophobic attitudes.

In studying the history of South African immigration policy, the shortcomings become evident immediately. As a regional economic powerhouse, South Africa has long attracted migrants from across the continent seeking employment, particularly low-skilled, low-wage foreign laborers to work in its booming Apartheid-era mining industry. The majority of immigrants were undocumented or came on select temporary work visas with strict regulations curtailing individual mobility. In 1986, the Aliens Amendment Act made it possible for skilled immigrants – especially from East and West Africa – to legally move to South Africa. This made South Africa a haven for those seeking to flee persecution in the home countries.

In 1991, however, the Aliens Control Act – dubbed the last significant Apartheid-era legislation – significantly restricted the status of immigrants; the use of the word “Alien” to describe foreigners immediately implied “otherness” and illegality, and the vagueness of the implementation and enforcement mechanisms empowered ordinary citizens to report foreigners they suspected of breaking immigration laws. In 1998, the Refugee Act recognized refugees as an immigration category and ordered the issuance of asylum to those who could prove political persecution in their home country. Continued international scrutiny of the failings of South Africa’s immigration policy in light of xenophobic incidents and attacks led to the 1999 White Paper on International Migration, which acknowledged the role that skilled migrants could play in filling in critical labor gaps and recognized the potential benefits of migration for South Africa.

However, the White Paper continued to address people who were not South African citizens or permanent residents as “aliens,” estimated the number of illegal immigrants in the country to be 5 million (which was grossly inflated and contributed to a popular perception of “invasion”), and emphasized the importance of training police and local authorities to address xenophobic behavior but provided no clear recommendations for the content of this training and no clear repercussions for the police if they failed to conduct training. After the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance was held in South Africa in 2001, the government founded the National Forum Against Racism and created the Counter Xenophobia Unit, but nothing was ever produced as a result. In 2002, the landmark Immigration Act replaced the term “alien” with “foreigner,” and directly addressed prevailing xenophobic fears about foreign economic integration in the preamble.

However, there has yet to be any clarity or direction on who is performing immigration control and how xenophobia is to be prevented and countered. These responsibilities fell largely onto the Department of Home Affairs and local law enforcement units, which were wholly unprepared to deal with such tasks. Finally, current immigration policy is focused more on internal control and enforcement activities, rather than border control; these policies have not served to constrain undocumented migrants or stem the flow of immigration but rather, have led to a massive increase in forged documentation and police corruption and bribery to escape arrest and deportation.

Law enforcement tends to act in accordance to personal value systems, and are oftentimes indifferent to the welfare of immigrants. Without special training, law enforcement can act as aggravators in sensitive situations, and only serve to contain, not prevent or address, xenophobic violence and attitudes. In fact, South African law enforcement regularly arrested and detained people on the basis of their physical appearance, language, or fitting a certain “profile”; they are also known to refuse to recognize work permits and refugee identity cards while enabling illicit economies and rampant corruption –bribes for freedom are common, as police see foreigners as “mobile ATMs.”

Government failure of responsibility to take the lead in addressing xenophobic attitudes has practically served to legitimize xenophobic violence. A former Minister of Home Affairs, Mongosotho Buthelezi, who was in a prominent position to set the tone of the discourse on immigration, commonly used the term “illegal aliens,” inflated the number of said “illegal aliens” within South Africa, and insisted upon a causational relationship between immigration and poor economic performance: “We are to scramble for resources with these illegal aliens – we might as well forget the Reconstruction and Development Programme,” and “South Africa is faced with another threat, and that is the [South African Development Community] ideology of free movement of people, free trade and freedom to choose where you live or work. Free movement of persons spells disaster for our country.” In early 2015, Small Business Minister Lindiwe Zulu said “Foreigners need to understand that they are here as a courtesy and our priority is to the people of this country first and foremost.” Even the widely respected Human Sciences Research Council used derogatory terms such as “hordes” and “floods” to describe undocumented migrants in presenting research findings.

Political Failure

The African National Congress, despite being elected on overtures of reform and change, has failed to deliver on its promises, and its lack of response on xenophobic issues has done nothing to quell the violence. The Apartheid-era government partially sustained itself by promoting rivalries between “traditional” tribal authorities and ANC nationalists. When campaigning in the 1994 elections, the ANC evoked religious references when speaking about liberation, as if overthrowing Apartheid would lead South Africa to a promised land. However, the ANC has failed to create effective and responsive forms of government; power has become centralized within the ruling elite, and local governance has suffered.

Over the years, the ANC became perceived as out of touch with poor citizens and having failed to deliver jobs, services, and security. During a period of xenophobic violence in the 1990s, the ANC was decried as being “more concerned with its foreign policy concerns and repairing any damage the attacks might have on their international reputation” than with addressing the root causes of the issues. Through examining the structure of the ANC’s ruling coalition, a major fault becomes clear: in building the coalition needed to win the historic 1994 election, the ANC had to co-opt ethnic leaders such as Zulu King Zwelithini – who espoused a brand of ethnic chauvinism that appealed to young, poor men – by putting them on the state’s payroll as part of a group called the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa, legitimizing the ethno-nationalist politics which the ANC had opposed. King Zwelithini’s xenophobic comments at an event in early 2015 are widely believed to have sparked the second round of riots in April 2015. Disillusioned with the ANC, impoverished black South Africans who are searching for answers to their woes are increasingly looking to leaders like King Zwelithini who champion xenophobic scapegoat solutions. The ANC, facing a popular uprising, recognizes the value in funneling discontentment with itself into xenophobic outlets and deflecting the blame off its own policies. The failure of the South African government, broadly speaking, means that the citizens have taken it upon themselves to act. Poor South Africans’ hostile anti-foreigner attitudes are rooted in their acquisition of full rights and benefits of citizenship; they view foreigners as threatening or undermining their benefits.

A quote from a participant in the 2008 riots reveals his motivations: “We are not trying to kill anyone but rather solving the problems of our own country. The government is not doing anything about this, so I support what the mob is doing to get rid of foreigners in our country.” The lack of commentary by senior political leadership and refusal to acknowledge xenophobia worsens the problem. Even Nelson Mandela, in a speech on the National Day of Safety and Security, once said “the fact that illegal immigrants are involved in violent criminal activity must not tempt us into the dangerous attitude which regards all foreigners with hostility,” which furthered the perception and association of all foreigners not just with illegality but criminality.

Recent Developments

From an analytical standpoint, the South African government has failed to address the recent xenophobic attacks in a constructive or even logical manner. After the violence in 2008, hundreds of thousands fled into temporary immigration camps; then-President Mbeki denounced the camps, which would entrench spatial divisions between foreigners and South Africans and thus formalize the objective division between both; he argued instead in favor of “reintegration”: people should go back to townships and live together with the same neighbors who had attacked them. Yet Mbeki gave no indication as to how to re-integrate, and when a police commissioner was interviewed in Alexandra township – ground zero for the attacks – and asked who was in charge of overseeing reintegration, he responded “My job is stabilization, not re-integration.”

Following the xenophobic attacks in early 2015, the South African government launched “Operation Fiela,” deploying the police and military to combat crime throughout the country in coordinated waves. The timing, right after the attacks, as well as the operation locations in many immigrant strongholds, was tantamount to equating foreigners to criminals; xenophobia had, for all intents and purposes, officially become a politically expedient excuse. Foreigners who were caught in the Operation were granted dubious legal protection; it was likely that people were arrested without cause and deported without legal representation.

Conclusion

After analyzing South African immigration policy and xenophobic attitudes from a historical perspective, it becomes clear that the outbreak of xenophobic violence was part of a legacy left behind by Apartheid and ethnocentrism. The three main failures by the ANC-led South African government (to establish economic growth, social integration, and strong institutions) caused poor South Africans to construct outsiders into bogeymen and scapegoats, and the institutions meant to address inequality not only failed to do so but actually enabled violent xenophobic attitudes. As a discourse, xenophobia – and foreigners – will continue to be an expedient political tool the ANC channels so long as economic issues and political infighting persist in South Africa. Unfortunately, the lopsided victims of the status quo will continue to be the impoverished millions fighting for survival in the crowded townships, who see no solution to their problems and no agency other than through violence. A quote summarizing the situation comes from Nana Mkhonde, a resident in Durban’s impoverished Bottle Brush settlement following the 2015 attacks:

“Our citizens took action because [the foreigners]wouldn’t leave and they were being told they must leave. They came with nothing, they can go with nothing as well. I feel bad because they left crying, but we have no choice…they should go because we have no jobs. I’m a citizen and want to work for 150 rand a day but foreigners will do it for 70 rand a day. In the kitchens and the factories they are taking over our jobs. They bring cheap goods and we don’t know where from. They leave their countries with a lot of skills and we have nothing. Our education is not good enough…The government says it’s wrong because when they give jobs they help themselves. If you don’t have friends in the ANC, you get nothing. What about us? Our government is doing nothing for us. The reason we’re fighting foreigners is because of our government.”[1]

[1] Smith, David. 2015. “Xenophobia in South Africa: ‘They Beat My Husband with Sticks and Took Everything.’” The Guardian, April 17, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/17/xenophobia-south-africa-brothers-violence-foreigners.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.