Introduction

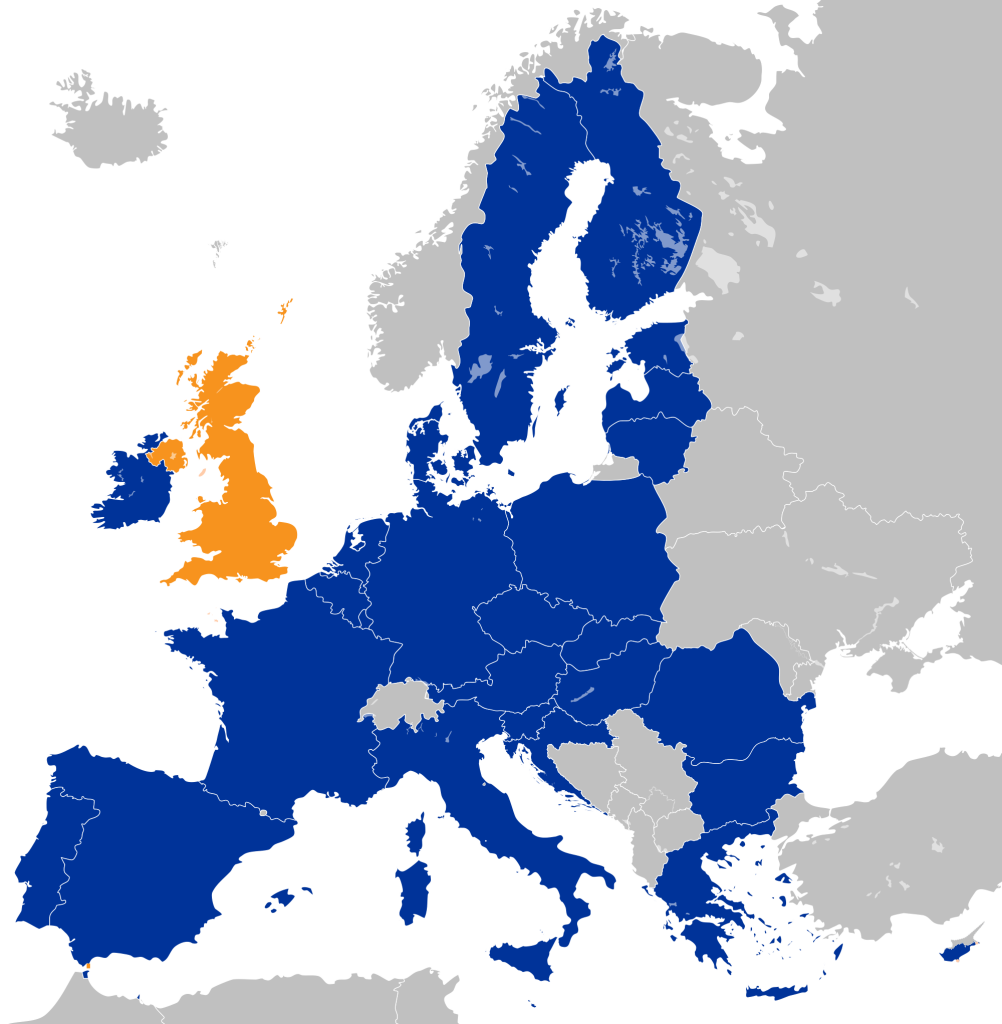

Recently, the EU has undergone significant changes due to external factors including, but not limited to, the 2008 economic crisis, the Arab Spring uprising, the emergence of Islamic State in the Middle East and the Syrian refugee crisis. Combined with the European Union’s already shaky sense of identity, these events have heightened tensions among and within states. In the UK, the trend of Euro-skepticism among a portion of UK citizens led Prime Minister David Cameron to promise to hold an EU referendum. Although the UK has always had a more distant relationship with the EU than other member states have, on June 23, 2016, the UK surprised the international community by choosing to leave the union.

Assessing the Current Situation

Britain’s exit from the EU, commonly referred to as Brexit, has created a host of economic and political issues for the EU, UK and the wider international community. For the EU, its size and stature in the global arena may be significantly decreased, as the union is losing over sixty-five million people and 94,525 square miles. Even more importantly, the UK is the second largest economy in Europe and the fifth largest economy in the world. Not to mention, London is arguably the most competitive financial center in the world. Without the UK’s large market and its economic status, the EU may experience a decline in internal movement of capital and may also have a harder time obtaining favorable trade deals externally.

For smaller member states, this is particularly worrisome as the UK is no longer present to act as a counterweight to Germany’s dominance in the economic sector as well as France’s dominance in the political arena. While some argue that the two remaining powers will balance each other out, Germany is still very much a reluctant hegemon in Europe and may be unwilling to go toe-to-toe with France. Furthermore, the UK has served as a bridge between the EU and US in the past. A more distant US leads to an even larger power vacuum within the union.

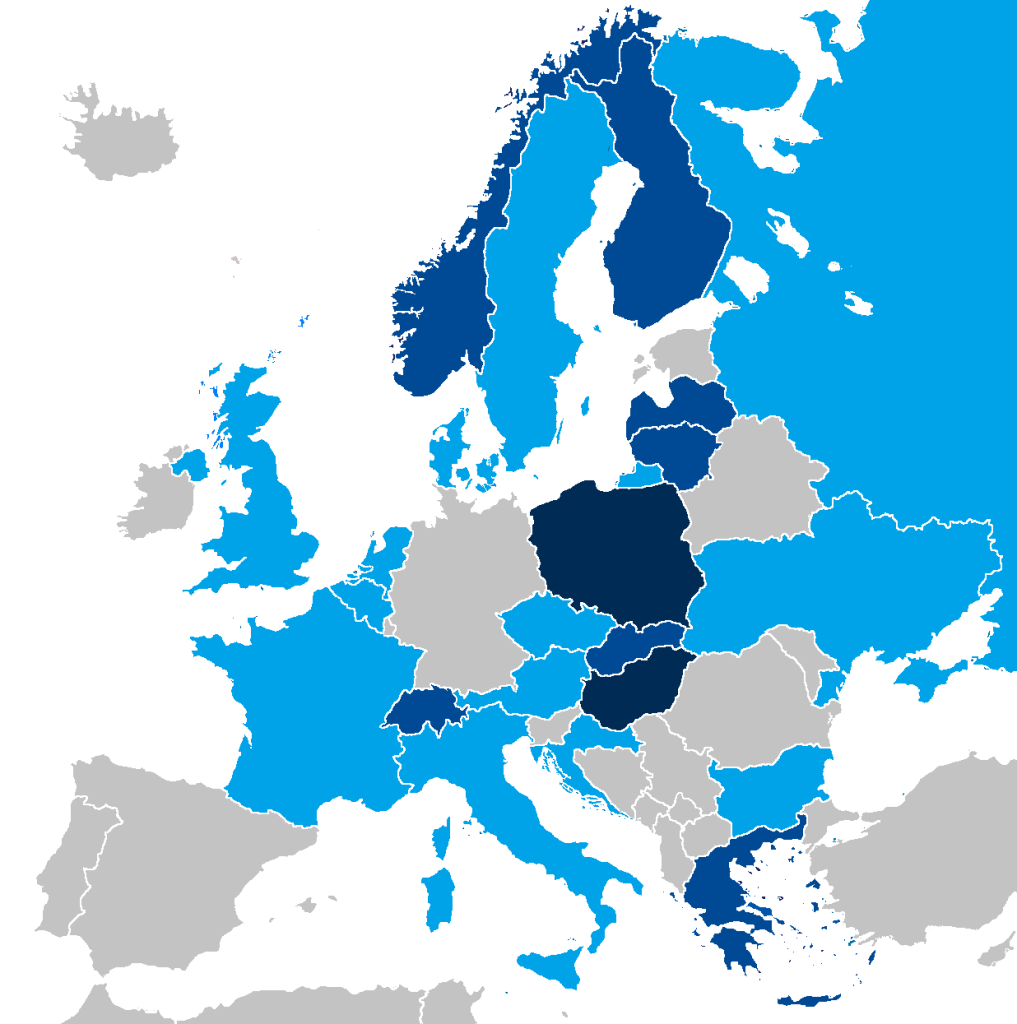

The instability caused by this change might encourage other disenfranchised member states to think about leaving due to a perception that the union is disintegrating. As general anti-immigration and anti-establishment sentiments have increased, a wave of populist discontent with the status quo seems to be sweeping across Europe. Right-wing parties have grown in power, either surging in popularity, as is the case in France and Germany, or even taking control of the government, as is the case in Finland, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania. With leaders of populist Eurosceptic parties in countries such as France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany and Sweden proposing to hold their own EU membership referendums, many fear that Brexit may have triggered a chain reaction that will ultimately lead to the dissolution of the UE.

Yet, for Britain, there are even larger implications. In terms of the domestic political situation, Prime Minister David Cameron of the Conservative Party resigned, leaving Theresa May to step in as the new Prime Minister. Although she is the leader of the Conservative Party, she is seen to have a more balanced stance than her predecessor, which will change the political climate of the UK. To add to the turbulence, with the UK leaving the union and sixty-two percent of Scottish voters wanting to remain in the EU, another Scottish UK referendum has been proposed. Although the one in 2014 narrowly failed, a future referendum may prove successful, as many analysts believe the majority of Scottish citizens would prefer to be part of the EU over the UK.

Outside of policy, the economic effects of the EU may have an even larger role in the future of the UK. Immediately after the announcement of Brexit, the British pound decreased in value to an over thirty year low and over two trillion dollars were wiped off shares globally. Perhaps most importantly, many bilateral trade relationships must be renegotiated or formed as the EU has many standing relations that the UK will no longer a part of.

Policy Proposals

The next steps for managing UK and EU relations must fall within the provisions of Article 50 of the Treaty of the European Union. Now that Prime Minister May has officially triggered Article 50, divorce talks with the EU are underway. According to the first two sections of this article, although the member state may choose to withdraw based on its own methods—in Britain’s case, a popular referendum—the EU must negotiate and settle on a withdrawal agreement with the member state in the next two years. This may be an arduous process as member states often find it hard to agree on topics of importance. Although there are many routes that the UK can choose to take, three categories of viable options exist for these negotiations when determining the implementation of their exit from the EU.

The first of these constitutional options would be for the UK to make a relatively quick and complete break from the EU, including all its institutions and organizations. If the UK chose this option, it would have to fill the legal vacuum of EU legislation with its own new regulations in regards to areas such as customs, transport, food production, agriculture and fisheries. The nation would also have to form a completely new identity for itself and relationship with the EU, as well as other countries that have relations with the EU. For example, within Europe, the UK will have to redefine its relationship and set up new trade agreements with countries such as Switzerland and Turkey. Internationally, the UK would have to establish new bilateral relations while considering the effect on current trade partners and trilateral relations in circumstances where the EU already had or is in the process of developing bilateral relations.

Known as “hard Brexit,” this approach may take more time to implement given the many new regulations that will have to be formulated and approved. Undoing all the treaties formed over the 43 years that the EU has been around and determining how to fill the vacuum left is further complicated by the fact that the move to leave the EU is unprecedented. According to foreign secretary Philip Hammond, the whole process, including negotiating a new trade deal, will most likely take between four to six years, clearly over the two year provision of Article 50. However, if this happens, the EU-UK relationship will default to the mechanisms outlined by the WTO. This may be extremely detrimental, as it would mean EU’s external tariff would include trade with the UK.

The second option would be for the UK to attempt to maintain as much of its current relationship as possible. In order to do this, the UK would probably try to stall the actual implementation of leaving the EU and all its institutions and organizations. During this period, it would try maintain old and establish new economic ties by negotiating a bilateral free-trade arrangement with the EU block. Because Article 50 states that the withdrawing member state will remain within the EU until an agreement has been reached, the UK will have a buffer period to determine how it will proceed in the future. During this time, the UK will continue to have a say in EU proceedings and influence policy other than those directly concerning its withdrawal. The UK could use this opportunity to secure favorable trade agreements and international deals that will benefit both the EU and UK and will allow them to work as partners in the long run.

The difficulty with this option lies in convincing Euroskeptics, including sixty Tory MPs, to accept the compromise. They maintain that in this scenario, the UK would not truly be a sovereign nation without the ability to negotiate its own bilateral trade deals or implement its own border controls. Because this would require the UK to continue to accept certain policies and agreements that come with being a part of the EU, such as unlimited EU migration and required payment into the EU budget, “hard Brexiteers” may argue that this defeats the purpose of leaving the EU.

The third option lies somewhere in between these two choices. This would allow for a “customized special deal” for the UK, where the UK and EU would choose which part of EU membership to apply to the UK. For example, the UK could opt out of more costly and less popular portions of membership such as free movement or budgetary contributions. In fact, while the UK was still a member of the EU, it had already opted out of many of these institutions and agreements, such as the European Monetary System and the Schengen Agreement. Out of all the options, this one seems most probable because it would cause the least amount of political and economic disruption with the most benefits for both the union and the UK.

One proposed mechanism to facilitate this process and ease the transition is known as the Great Repeal Bill. This piece of legislation would initially copy all EU laws into domestic laws. These placeholder laws could then be changed or repealed by the UK Parliament. Yet even if this bill is passed, there are other significant obstacles to overcome. For one, revising each law on a case-by-case basis may be overly ambitious, as the UK government will have many other external issues to deal with. Also, trying to negotiate a favorable trade deal without paying EU dues will be extremely difficult and may lead to a prolonged process of formalizing the withdrawal.

Conclusion

In light of the many factors that are tied to the UK’s former role in the union, Brexit has deep and lasting implications. Political and economic repercussions within the continent and internationally are hard to determine, but may demand immediate solutions. Already, Prime Minister May has called for snap elections on the grounds that this will help the UK in the upcoming Brexit negotiations by unifying Westminister. Whichever option the UK decides to pursue, as an international power, it has a duty to establish its new position and the world and re-assert its leadership in various spheres of power and specific international organizations. Whether or not this change will lead to more positive or negative consequences remains to be seen.