Population control is one of the least sexy platforms a politician could embrace today. The very term connotes coercive family planning practices like China’s one-child policy, or worse, forced sterilization. And yet, overpopulation contributes to or exacerbates almost all of the world’s most pressing issues. Policy-makers and politicians striving to deliver messages of optimism ignore the unpleasant reality: our planet has a carrying capacity and we have a collective responsibility to adhere to its limits. A comprehensive, global approach to halting population growth should top our leaders’ agendas.

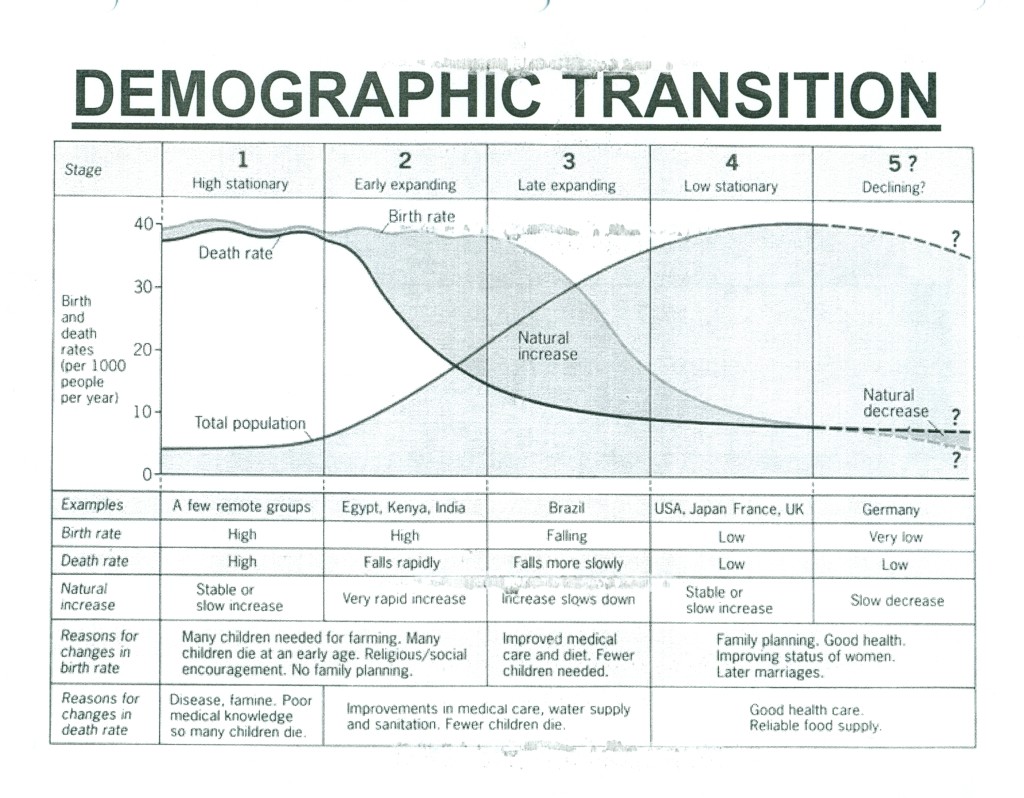

At the time of the writing of this article, world population was nearing 7,304,020,300. In just about 200 years, this figure increased sevenfold from one billion; during the twentieth century alone, it ballooned from 1.5 to 6.1 billion. To understand the reason for such drastic growth, let’s review the basics of the demographic transition model, a key concept in population theory.

In the late 1700s, death rates began falling in countries with medical and technological advancements. During the industrial revolution, people became more and more likely to survive childhood and reproduce. Before, populations had been held largely stable throughout human history by high birth rates and high death rates, but when mortality rates fall and birth rates remain constant, the population skyrockets. In later phases of the model, birth rates fall to the level of death rates and the population stabilizes once more, though at a much higher number. While developed countries have already passed through the stages of this model, most of today’s world lives in the intermediate stages of demographic transition, the largest countries still undergoing rapid population growth.

Population growth in itself is not a negative phenomenon—a growing number of young people means a larger labor force for a country, which can facilitate economic growth. The problems arise when populations verge on exhausting the earth’s resources, many of which are finite or impossible to replenish quickly enough to support 11.2 billion people, the current 2100 projection. With most carrying capacity estimates ranging from 9-10 billion – for a predominantly vegetarian population – these figures should arouse some concern.

Increasing consumption destroys ecosystems and causes every sort of ecological disaster, from biodiversity loss to deforestation, pollution and climate change. In the words of Thomas Johansson, Director of the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Energy and Atmosphere Programme, “Ecosystems provide essential services like climate control and nutrient recycling that we cannot replace at any reasonable price,” meaning that our civilizations rely on the very resources we currently deplete.

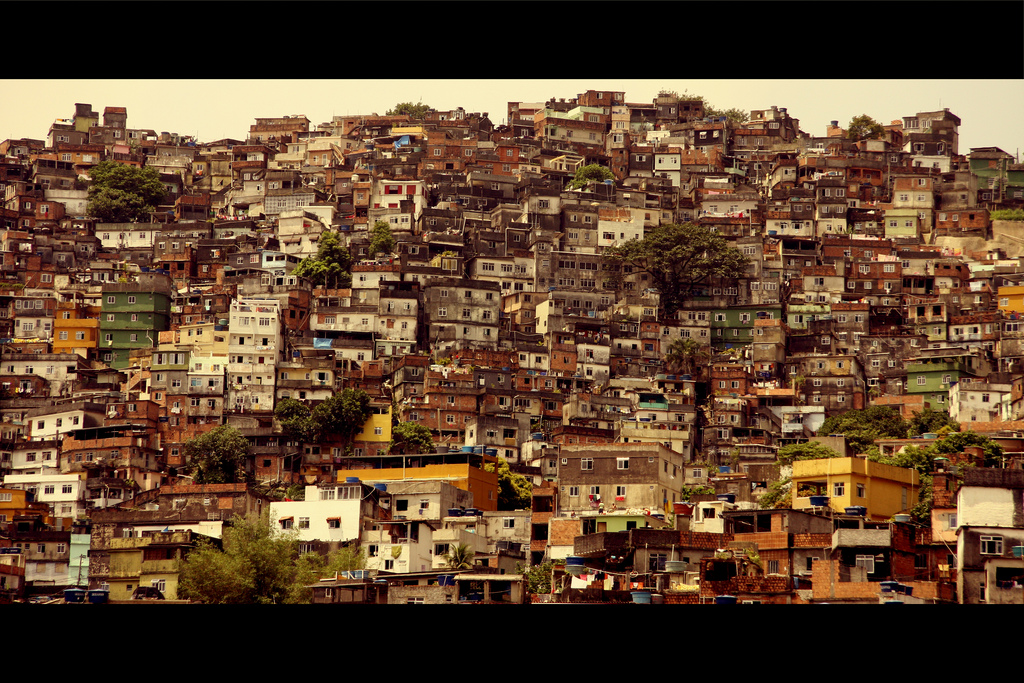

Typically seen as a vice of the developed world, overconsumption in less developed countries also plays a role in environmental degradation. When there are too many people for available resources to sustain, poverty ensues, and impoverished people often have no choice but to destroy their environment in order to survive. Take Nigeria, for instance: last August, the Chairman of the National Populace Committee, Eze Duruiheoma, revealed that his country’s existing infrastructure, food supply and level of economic opportunity could no longer support an exponentially growing population. He even linked population demographics to national security challenges like “militancy in the Niger Delta, Boko Haram, conflicts between farmers, among others.”

It’s clear that dramatic population growth can breed instability, becoming an underlying cause of many of today’s violent conflicts. There is a common consensus that a large, discontented young population limited by a lack of economic prospects can easily fall prey to radicalization. Acknowledging that “young, disenfranchised people” are a main target for terrorist groups’ recruitment strategies, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged for “education” and “engagement on the global level” to prevent violent extremism among the world’s youth in a 2015 Security Council debate on the topic.

Council members acknowledged “push” and “pull” factors that made young people easy targets for terrorist groups – “poverty, marginalization and unemployment” and “desires for financial gain, protection and solidarity” – and put forth constructive suggestions for countering terrorist groups’ appeal with alternate messages.

But there remained a huge elephant in the room that no one would touch, the underlying cause that created such an environment in the first place: rapid population growth that exceeds carrying capacity.

While it is imperative to craft creative, global solutions within the world’s current framework, we must not shy away from taking a stance on population growth that isn’t as PR-friendly for the UN as advocating for the “unleashing of young people’s energy and idealism.” The fact remains that the longer the world’s population keeps increasing, especially in poor countries straining to sustain themselves, the more prone the world will remain to violent conflict.

To preserve our planet and human life as we know it, the global community must take swift and sweeping measures to bring population growth under control, but we need not resort to unpopular and inhumane measures. The best way to lower birthrates, demonstrated again and again, is to give women full control of their reproductive rights through education and access to family planning. Unfortunately, this seemingly simple solution is often complicated in practice. In many cases, deep-seated cultural or religious factors stand in the way, but even in countries where these are most deeply entrenched, reducing fertility rates is feasible with a bit of creative thinking. In the words of Carl Haub of the Population Reference Bureau, “It took the US 200 years to go from seven babies per family to two. Bangladesh has done that in 20. Iran has more than halved its fertility rate in a decade.”

For decades, Iran has experienced a remarkably quick demographic transition as fertility rates have dropped to replacement level or below, the phenomena spread evenly across age groups and rural and urban environments. According to a UN analysis, Iran’s 1980s family planning program experienced such success due to the congruency between government policies such as “rural development, health improvement, and the rise of literacy” and sociocultural trends. Iran’s example demonstrates that by investing in related aspects of their citizens’ welfare, like education for girls, a reliable and accessible healthcare and even transport and communications can indirectly help curb population growth.

Women’s education in particular has remarkable potential to transform a country. A 2001 study of Iran concluded that access to higher education not only sways women’s fertility choices to later childbearing and smaller families, but also proclaimed that “Iranian women with rising expectations are an accelerating force of development in Iran.”

All evidence demonstrates that when women control their own reproduction, birthrates drop while health and quality of life improve for both mother and child. If governments and international regimes like the UN could swallow their discomfort with addressing overpopulation and champion humane, effective measures for halting population growth, there is no doubt that we would see an alleviation of poverty, and in turn, violent conflict. But most importantly, we’d certainly ensure a greater quality of life for generations of humans to come.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.