This past week, the Turkish Chief of the General Staff sailed along the coast of a set of Aegean islands that have been the center of contested claims between Turkey and Greece. The following day, the Greek government announced that Turkey had imposed upon Greek airspace 138 times in less than 24 hours. The Greeks and Turks have a long history of fighting over islands in the Aegean; but this most recent quarrel may extend to pollute the ongoing negotiations on the island of Cyprus.

A seemingly endless concern, the nearly half-century long conflict between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots ranks as one of the top foreign policy issues for both Turkey and Greece. There has been no violent conflict between the opposing sides since 1974; however, this does not mean this issue is not a concern for international policymakers. Recent diplomatic developments have lead to the possibility of a compromise, but even this prospect for negotiation may not be enough considering the problem’s deep-seated roots, as well as the recent tensions.

Historically, Cyprus was part of the ancient Greek Empire before being conquered by the Ottomans in the mid-14th century, who ruled the island for nearly three hundred years. After gaining its independence, Cyprus fell under British influence when the possibility of reunifying with Greece seemed to a feasible reality. But instead of taking into account Cypriot sentiments of Enosis, or “union” (with Greece), the British took Cyprus as one of their own colonies. They continued to rule the island, although pleas for unification increased. In the following years, Cyprus underwent significant political and social turmoil, ultimately resulting in the schism of the island, with the north being controlled by Turkey and the south by Greek Cypriots.

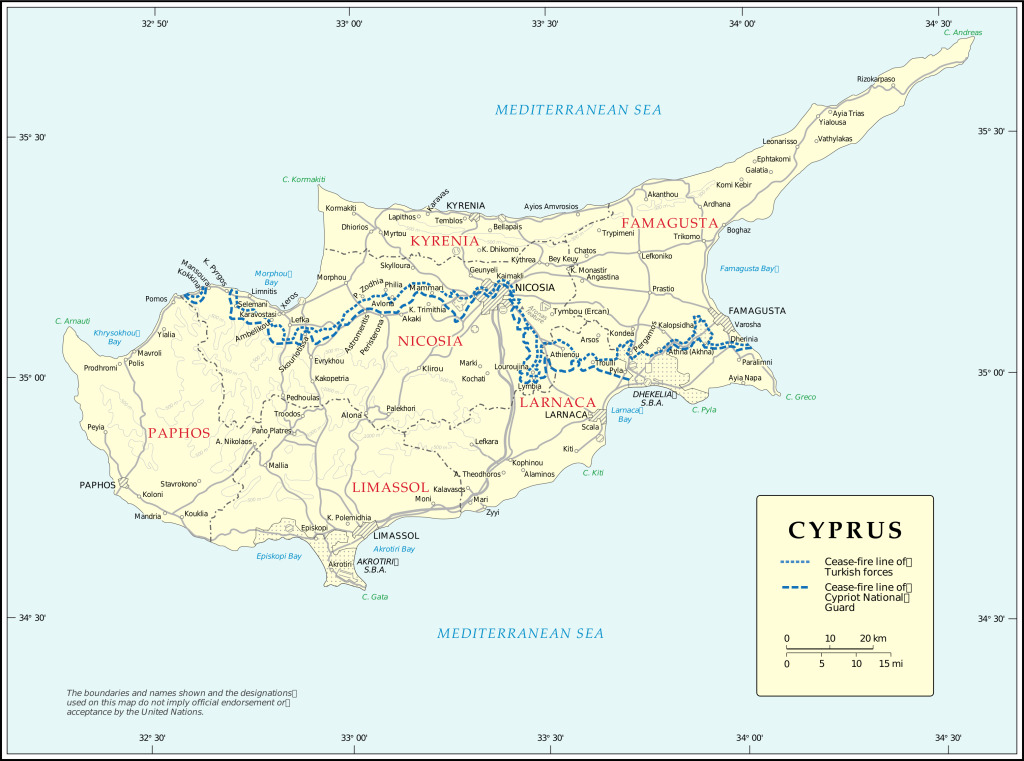

For over four decades, tensions have been high for the officially divided island which has resulted in a major source of conflict between European countries and Turkey. The north, occupied by Turkish Cypriots, is predominantly Muslim while the south is Greek Orthodox—a major point of contention. The south is also more gentrified, resembling a European city, while much of the north remains unchanged since the 1970s. Cyprus also hosts the longest serving peacekeeping mission in UN history, frustrating Cypriot desires to govern themselves as a sovereign entity.

In 2004, the international community finally recognized the growing tensions between Turkey and Greece, and the United Nations Secretary-General at the time, Kofi Annan, proposed the Annan Plan by which the future of the island would be put to a referendum. This plan aimed to create the United Cypriot Republic, which would be a federation composed of two states, each with their respective governments but sharing a bicameral parliament. Ultimately, the Annan Plan was unsuccessful, largely due to external pressure from Greece placed on the Greek Cypriots.

Greece’s political hold on the Cypriots stems from the Greeks’ firm national identity, which still continues to influence Cypriot politics after nearly 50 years of quasi-independence. Greece considers Cyprus to be a part of the Hellenic nation, meaning that to the Greeks, Greeks and Cypriots are the same in culture, heritage and ethnicity. Although Cyprus is its own state (being politically sovereign and distinct from Greece), ethnically and ideologically, it is Greek.

After this failed attempt to solve the problem, talks renewed once again in 2014 between Nicos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akinci (the political leaders of Cyprus) but did not last long because within a few months, Anastasiades unexpectedly pulled out, claiming that the Turkish side was acting “provocative” and “aggressive.” Matters were made even worse when Turkey announced its plan to begin offshore test-drilling near Cyprus.

In 2017, negotiators brought optimistic spirits to the table and in mid-January, talks resumed in Switzerland. The negotiations were sparked by an EU-UN partnership focusing on the reduction of violence, particularly in Europe and surrounding regions. Even Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has prioritized the issue, stating that the international community is in search of “a solid and a sustainable solution for Cyprus, for the people of Cyprus.” Still, he acknowledges that the process will be long and arduous. Both sides have been meeting to discuss the future of the island and what a unified country would look like. Topics of discussion included the formation of a federal government and the possibility of a rotating presidency, although this has been complicated by the upcoming Greek Cypriot elections planned to take place in May 2017. Being a larger population, the Greek Cypriots are fixed on the idea that they should have more power while the Turkish Cypriots fear the prospect of becoming a repressed minority. A great emphasis has also been placed on the issue of displaced persons and whether or not they should be allowed to return to their original homes. If a deal is struck, large land exchanges could take place, and each side fears relocation and the loss of entire homes and towns. The main concerns of the Greek Cypriots include the fact that Cyprus is part of the EU but Turkey does not recognize it as a country along with the presence of 40,000 Turkish troops settled in the north of the island. On the other hand, the Turkish Cypriots are most concerned with equal representation.

While prospects for reunification seemed strong in the first weeks of 2017, matters have become bleaker given two escalating disputes between Greece and Turkey: an island dispute and an extradition controversy. Two small uninhabited islands have once again come to the center stage of Aegean politics, with each country pursing its claims. The debate seems to be more ideologically fueled, especially given the recent decision of the Greek Supreme Court concerning the extradition of eight Turks that fled to Greece after the failed coup d’etat last July. The Greek court system is protecting the rights of those individuals and refuses to return them to Turkey.

Although no specific change has been made in the Cypriot negotiation plans, the talks are in severe danger. The political attitude continues to worsen and both Greece and Turkey are approaching the issue myopically and with the past still in mind. There are both skeptics and optimists on each side of the issue, but the recent political events between Greece and Turkey have left many doubting that the stalemate which has frustrated diplomats for over four decades will finally come to an end.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.