Correspondent Steve Helmeci wrote an interesting and critical piece on Secretary of State Hillary Clinton for Glimpse this year. The thrust of Helmeci’s argument is this: Hillary Clinton expounds an “outdated and dangerous” strategic ideology, which he refers to as “Cold War-era Realism.”

Clinton’s Cold War-era Realism, in Helmeci’s understanding, “operates under the assumption that any international entity not pro-US must be anti-US.”

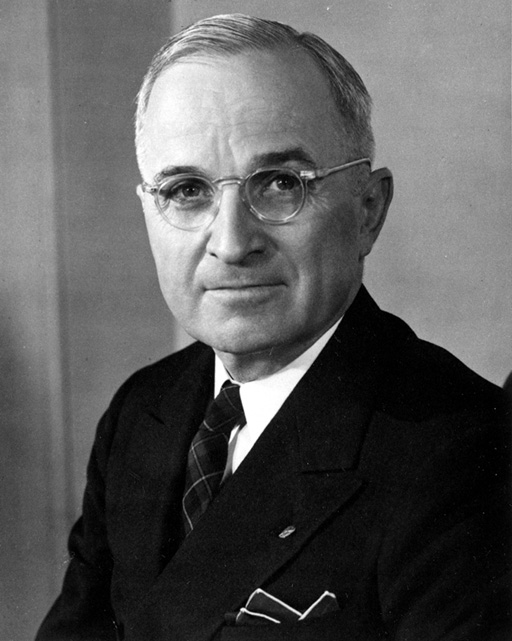

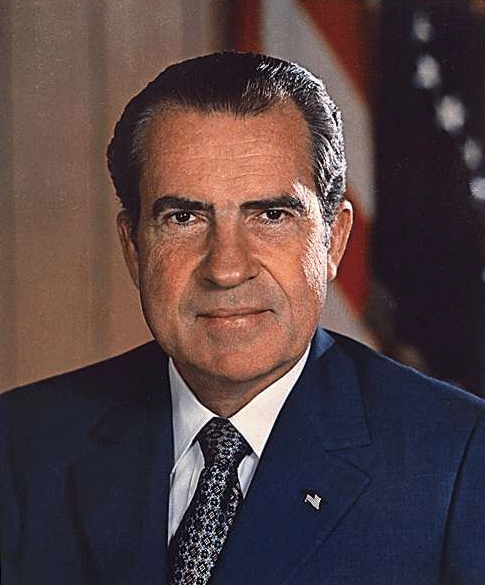

I take exception to Helmeci’s characterization of “Cold War-era Realists”, not least because I consider myself to be one. But more importantly, the figures he calls “Cold War Realists” — Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan (not directly, but implicitly through his reference to Margaret Thatcher)— each represent a very different strain of Realism that cannot be simply reduced to a Manichean, us-versus-them mentality.

So what was Cold War Realism? It could be considered a stool that rested on three legs of equal importance, as best described by George Kennan’s X Article and Long Telegram: First, a defense of the American-led international trading order encompassing US Arab Allies, NATO and liberal East Asian states like Japan and South Korea; Second, containment of the Soviet Union through power-balancing in strategic regions of Eurasia; Third, a defense of American principles of liberty and democracy in the face of the Communist threat.

The different strains of Cold War Realism embodied by Truman, Nixon and Reagan each emphasized a different pillar of the bipartisan consensus around Cold War Realism, without neglecting the other two. They made for very different types of strategies, all in the service of the same overall goals.

The Democratic Party of the 40s, 50s and 60s followed the international order-building tendencies of Franklin Roosevelt. President Harry Truman, along with Democratic Internationalist assistants like Dean Acheson and John Foster Dulles, were the real enablers of the NATO alliance, the trade arrangements and the Marshall Plan that grew so crucial during the long conflict with the Soviets. Other Democratic Internationalist presidents like Lyndon Johnson carried the tradition through. They were prone to interventionism—Democratic Internationalist presidents got America embroiled in both Korea and Vietnam.

Reacting against these sorts of internationalists were the Republican Power-Balancers, like Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. Where Democratic Internationalists focused on the international order leg of the stool, Republican Power-Balancers focused on its power-balancing aspects—hence Eisenhower’s refusal to support American allies, the British and the French in the Suez Crisis, and President Nixon and Secretary Kissinger’s legendary trip to and recognition of the People’s Republic of China. More concerned with keeping order than with promoting principles, this kind of strategist was often accused of being un-American.

Thus, after periods of retrenchment and recalibration, Neoconservative Hawks, or their Democratic equivalents, came to power, promising a return to values-based foreign policies. In some ways, President Kennedy was more a Neoconservative Hawk than a Democratic Internationalist. Just take his inaugural assertion that “we shall pay any price… to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” But the best representatives of this values-based anti-Soviet militarism were President Ronald Reagan and his assistant, Jeanne Kirkpatrick. The primary thrust of Neoconservative Hawks’ agenda was the defense and promotion of liberty and democracy abroad, as evidenced in Reagan’s support for anticommunist forces around the world but especially in Eastern Europe, and their harsh anti-Soviet rhetoric, as best exemplified by Reagan’s “evil empire” quote.

What About Hillary?

Now this leads us to another question—is Hillary Clinton rightly regarded as a “Cold War-era Realist”, and if so, which type is she?

Given the criteria Helmeci cites, it’s not clear to me that Secretary Clinton fits into the Cold War Realist tradition. Hillary’s yes-vote on the 2003 invasion of Iraq and her counsel to President Obama to topple Qadaffi and Assad in the name of human rights seem to indicate that the former Secretary of State falls into a very different and newer foreign policy tradition than that of the Cold War Realists: let’s call it the “End of History” camp.

Published in 1991, Francis Fukuyama’s essay, “The End of History”, basically argues that free markets, open societies and democratic polities represent the last conceivable form of human social organization. Thus all societies in the post-Communist world will begin to evolve, slowly or quickly, towards Western liberal norms.

Fukuyama did not literally mean that the United States should actively promote democratic transitions all over the world. Nonetheless, the American political elite generally interpreted Fukuyama’s essay quite literally, and did just that. A brilliant case can be made that the foreign policy strategies of Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama were each a version of the “End of History” overlaid onto traditional American foreign policy strategies.

For example, President Clinton made intensive efforts to expand the liberal international trading order as a global regime rather than a series of regional trading regimes. Under his administration, many believed that national sovereignty would slowly erode as globalization inevitably took its course. Clinton was what Truman would have been had Truman shared his optimistic outlook on the progress of history.

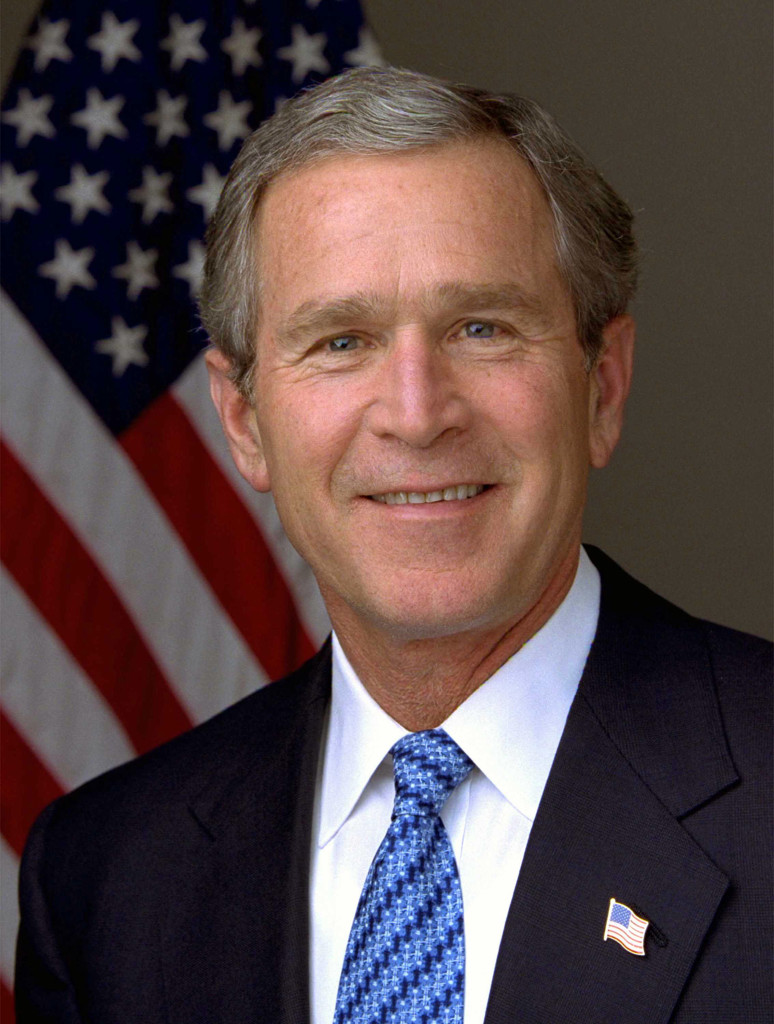

President Bush made efforts in his first term to spread democracy around the world by the sword, most notably in Iraq and most memorably through his “Axis of Evil” designation. Bush’s democracy-hawking interventionism was what Reagan’s neoconservatism would have been, had Reagan not displayed prudent restraint and a more limited view of freedom’s progress.

President Obama promised better relations with former American rivals around the world through a diminished American stance that assumed that natural balances of power would materialize as America withdrew her influence. Obama is what Nixon would have looked like, had Nixon not been cynical and tough-minded about human nature and international politics.

The strategies that post-Cold War presidents like Clinton, Bush and Obama have pursued have reflected the “End of History’s” intellectual understanding of a relatively benign human nature, cooperation rather than competition as the natural state of human affairs, and globalization and democracy as inexorably advancing developments pushed along by history itself. The strategies themselves — order building, promotion of American ideals, retrenchment and power-balancing — are not bad. But their application by political elites who lack a tragic understanding of human history is what has led to the vast gulf between the foreign policy successes of Truman, Nixon and Reagan, and the foreign policy failures of Clinton, Bush and Obama.

So where does Hillary Clinton fit into all this?

Based on her votes and counsel on the Iraq War and the Arab dictators, she seems to be not a Cold War Realist but an End of History democracy hawk like George W. Bush. That means that for the next four-to-eight years, we’ll probably have more of the same intellectually flawed, post-Cold War foreign policy we’ve had for the last three administrations.

Ideas really do have consequences—Fukuyama’s optimism and Kennan’s caution have inspired very different results.

But in an age of ascendant rivals abroad and terrorists lurking in every shadow, we need a mix between the internationalism of Truman and the power-balancing of Nixon. And we need a policy informed by understanding that jettisons the illusions of globalized democratic progress and benign human intentions. We need someone who will preserve the international order without attempting to impose it upon others. We need someone who can best protect the American way of life in an increasingly complicated and dangerous world.

We need a Cold War Realist.

Luke Phillips would like to thank Dr. Colin Dueck for providing inspiration for some of the ideas presented in this piece.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.