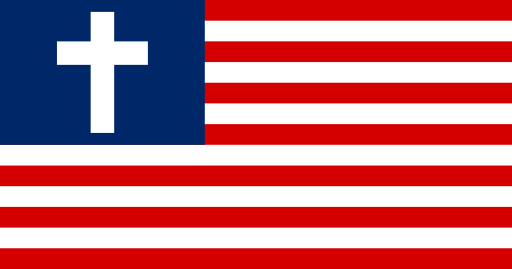

Many on the American Right often point to the ‘Christian’ roots of American political culture, usually arguing that the present decadent state of American society requires nothing less than a recommitment to the Ten Commandments and a national re-reading of the Holy Bible – interpreted, of course, through the lens of Evangelical Protestantism. A look at the actualities of American ideology reveals that the claim ‘America is a Christian nation’ is not wrong, but rather is correct in ways that would surprise and offend most social conservatives who would make that claim, and their liberal opponents who deny it.

Manifest Destiny, so often taught as little more than white patriotism justifying expansionism, is less about racial superiority (though historically that held significant appeal) and more about the superior ‘civilizing’ morality of the American nation justifying its preeminence among nations and thereby justifying its vigorous expansion. It held American hearts and minds from the turn of the 19th Century to the dawn of the 20th.

Finally, American Exceptionalism has been something of a synthesis between the previous two ideas. It teaches that, because America is the golden nation depicted by the City on a Hill, it uniquely reserves the right to spread its ideals to the oppressed peoples of the world.

Taken together, these ideas start to resemble the attitudes of crusading nations throughout history. That is because in its insistence on the justness of its own ways of thought, the United States has constructed for itself a civil religion. When looking at various case studies throughout recent American history – from the widely maligned arguments for the democratization of Iraq and Afghanistan, to the humanitarian rationales for intervention in Bosnia and Libya, to federal support for democratic regimes and movements across the Post-Soviet arc – the sheer irrational faith American policymakers have had in the rightness of their own ways is literally almost religious. Belief in the infallibility of democracy and zeal for its global dissemination quite simply depicts one of Christianity’s most important influences on American politics: the missionary tradition. Bear in mind that the United States has always been a majority Protestant nation, and thus Protestantism energizes its worldview.

But the correlation extends into the very substance of American ideals. As James Kurth brilliantly depicts in his article, “The Protestant Deformation,” Americans have shaped their political ideals with their religious ones. The 16th Century Protestant rejections of hierarchy, tradition and preeminent community, replaced with egalitarianism, reason and individualism, define the American creed about as well as any secular understanding. Protestantism, in particular, emphasizes the dignity and equality of all individuals, which are concepts enshrined in the US Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Oftentimes, these ideas are attributed to Enlightenment ideology and secular rationality. While this is directly the case, it is rarely mentioned that the Enlightenment and the faithful ‘secularism’ it engendered were the intellectual heirs of the Protestant Reformation. Had most early Americans practiced a religion other than Protestantism, it is extremely dubious whether the ideals that took root would ever have been developed, much less embraced, on American soil.

Yet, in the 20th and 21st Centuries, some might argue, the ideology has changed so much that it can hardly be called inspired by Protestantism.

However, I believe it still can. No matter how different one species is from its ancient ancestor, the linkage is still there, and in the case of American ideals the temporal space is really not that wide. The high regard for individual rights and privileges ubiquitous throughout American political rhetoric today – so deep-seated, in fact, that those who speak out against specific individual rights of any kind, be they rights of expression, property, political participation, or cultural issues such as abortion or marriage, are often derided as bigots and, in some extreme cases, even as fascists – is held not only due to a natural love of freedom or power, but also to a religious conviction that individuals are autonomous and should be treated by the state as such.

The implication of this is that those of all political stripes in the United States – if they subscribe to American ideals as justification for their ideologies – are living the classic American civil religion of faith in republican ideals, with a rooting in Protestant Christianity. And more often than not, these ideals translate into foreign policy attitudes and decisions.

It is important to note that every American who subscribes to the general American ideology, therefore, takes part in the Protestant tradition regardless of his or her own faith. I suspect the individuals most likely to object to this characterization are rational atheists who consider themselves secular. For my part, as a (poorly) devout Catholic and a proud American, I was originally somewhat disconcerted to discover the Protestant, and, at times, anti-Catholic roots of the political tradition to which I subscribe. But a realization of the fallibility and historical contingency of American political ideology, as well as of its general benevolence and, indeed, its tolerance and accepting attitude towards those of all religious traditions, have allayed my fears and allowed me to practice my political faith in a more nuanced light. I only hope that other thinkers bothered – or overjoyed, for that matter – at America’s fundamentally Christian nature can allow themselves to be sobered by that acceptance.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff and editorial board.