Since the start of 2014, approximately 1700 African migrants have lost their lives due to capsized boats during their journey from North Africa to Europe—the vast majority of incidents happening between Italy and Libya. A rough estimate indicates that over 170,000 migrants attempted the route last year. While exact statistics are impossible to determine, from the Libyan-Italian migration numbers one can surmise that hundreds of thousands of African migrants participate in the broader migration across the Mediterranean headed not only to Italy, but also to Spain, Portugal, France and Greece. The sea-journey has attracted the most European attention, being both the most dangerous and visible leg of the migration. But it is only part of a much longer trek starting in the African interior and ending in the packed boats along the northern African coast.

Poverty is typically a motivating factor for migration, but rarely the only one; the act of leaving one’s homeland is often far more risky than enduring the pains of hunger. More often it is poverty in conjunction with conflict or a humanitarian disaster that spurs the difficult decision to leave the homeland in search of a better life in Europe. Somalia, for example, has been a major source of Europe-bound migrants because of the famine and drought, along with the constant militant conflict. As of late, the conflicts in Libya, Northern Mali and Central African Republic have also pushed the most desperate to attempt a journey to Europe.

There are three ways that African and the growing number of Syrian and Middle Eastern migrants get into Europe. The first is through misuse or abuse of legal documents. By far the most expensive, only migrants with significant financial assets have the ability to purchase visas and other related documents from middlemen and smugglers. With fake or misused documents, migrants can take advantage of conventional modes of transportation (e.g. train, plane, ferry) to get to Europe, making it the safest and quickest option. The second method is through ad-hoc smuggling services, where the migrants travel on their own, occasionally using smuggling services for specific tasks such as crossing a border (e.g. crossing from Chad into Algeria) or procuring a boat to cross the Mediterranean. This is by far the cheapest option, but also poses the most danger due to travel across stretches of dangerous terrain (e.g. the Sahara) and sea with little guidance. The third and final option is pre-organized stage-to-stage smuggling, where smugglers organize and lead the whole journey. Between the first two options, this third option occupies the middle ground in regards to safety and cost, making it the most utilized of the three choices.

With many of the African migrants originating from central and even Southern Africa (e.g. Ghana, Eritrea, Uganda), the journey just to get to the Mediterranean coast can take longer than a year. Through a combination of vehicle, rail and foot, they make the dangerous journey across the African continent. National security forces repeatedly report finding dehydrated corpses of migrants in the Sahara desert, most recently in 2013 when 92 migrants were found dead in Niger. To avoid this danger many migrants opt for escort by smugglers, but because of the undeveloped infrastructure, the harshness of the environment and exorbitant smuggling fees, being escorted across the Sahara costs anywhere between €1000-3000 ($1100-3320). Thus, many migrants pay by leg rather than in full. Migrants make lengthy stops at regional hubs located in oases and towns all across Africa in order to make the minimum amount of money to pay for the next stretch of the journey. Without many formal economic opportunities, many migrants resort to black market activities during their trip, making migration hubs dangerous centers for the narcotics trade, prostitution and human trafficking.

Once migrants reach the North African coastline, they often pool their money in a large group to pay a smuggler or middleman to procure a boat. Crossing the Mediterranean can cost another €1000-2000 ($1100-2225). But even after pooling, the resulting sum is usually only enough to procure a boat that is old, too small and not very sea worthy. The price for safer rides is too high for most migrant groups because smugglers and middlemen take a significant portion in fees and payments.

Contrary to general opinion, the actual difficulty of the journey across Africa and the Mediterranean is not due to the lack of opportunity; the migrant network is extensive with many migrant hubs. It is well-traveled and for the most part, safe. Unfortunately, for most of the migrants, the lack of money makes the journey dangerous as it forces them to cut corners and enter unfavorable transactions. The migrants that do successfully arrive on Europe’s shores are often forced into bonded labor or European human trafficking networks because they paid for their journey through credit.

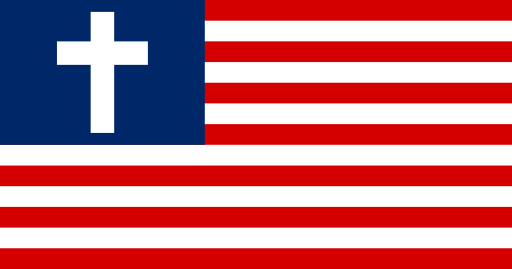

The ultimate goal for migrants is the freedom to live and work for their own benefit. The majority of migrants are working age men, seeking jobs to provide for their families back home. However, the physical and financial difficulty of the journey has made that goal nearly impossible to achieve. Remember that these migrants do not simply ride a boat across the Mediterranean—they traverse rainforest and desert in order to even have the chance of crossing the sea. This migratory journey is critical when crafting policies that prevent further loss of life on the Mediterranean and humanely integrate migrants into European society. Revising domestic immigration laws in order to make legal immigrant status (under the auspices of asylum or refugee status) easier to achieve will be immensely effective at allowing more migrants to avoid resorting to smugglers and dangerous routes. However, Europe struggles with significant conservative political and social forces that actively advocate for anti-immigration policies and prevent bold, decisive action. Even so, politically feasible options exist, including augmenting and readjusting aid budgets to build and expand current international refugee camps for displaced peoples, developing local safe havens. Rather than attempting to improve the situation purely through domestic legislation, Europeans should also work multi-laterally with African countries in a proactive fashion to allay the “push” factors of conflict and poverty, and improve the safety of the journey. Simply barring migrant’s entry is not a policy. Not in the face of thousands dying at the continent’s doorstep.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.