In Islamabad, Pakistan, people clamored for a reservation to sample the new and exclusive French restaurant in the heart of the city. The city is a hotbed for different cultures and people, where wealthy Pakistanis mingle with foreign diplomats and ex-pats, blurring lines and creating an international environment. ‘La Maison,’ a new hit with ex-pats, was being talked about around town. Excited at the prospect of sampling authentic French cuisine, the restaurant had reservations booked up to several days in advance. There was only one condition that had to be satisfied in order to gain entrance to the fashionable restaurant – proof that you weren’t Pakistani.

Philippe Lafforgue opened ‘La Maison’ in October 2013 with the idea of serving food for ex-pats working in the capitol city of Islamabad. Claiming that his foreigner-only policy was not discriminatory but rather culturally sensitive, Lafforgue argued that he did not want to be arrested for serving a Muslim customer an alcoholic beverage or a pork dish. Additionally, he claimed his dishes were not prepared in a halal manner with many menu items requiring the use of alcohol and that changing the ingredients of the recipes would compromise the authenticity of his French food. Like many Islamic nations, Pakistan has dietary laws imposed on its Muslim citizens, mainly, the ban of pork and alcohol. Although Lafforgue has a right to refuse serving Muslims alcohol, a policy found in many hotels throughout Islamic nations in the Middle East and Asia, he has gone farther than others by denying entrance into his restaurant despite hiring a Pakistani chef, bartender, kitchen and service staff.

In Pakistan, The restaurant has been met with criticism from both Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Journalist Cyril Alemida, who initially brought the restaurant’s discriminatory policy to light when he was rejected due to his possession of a Pakistani passport asked, “How does a foreigner run this money-spinning business out of the heart of the Pakistani capital, and not let Pakistanis in… And how does he get to ask me to produce my passport? He’s not an airport. He’s not an international authority. He’s not an embassy. How can he do this? Reserving the right to admission doesn’t mean an entire category of people [can be]written off.”

Many locals are crying foul and have reported the establishment to the police. “It’s absolutely ridiculous,” says Pakistani-American Bushra Mateen. “My family left their home, the country of their ancestors, and the home of all of their history, to start a new life free from oppression. We left, so that no one could reject us for our skin color or religion. And now this guy comes along and tells me I can’t eat in my own country. I am not a dog, I am not an Indian, I am supposed to be in my home.” Ms. Mateen refers to the “No Dogs and Indians” rule that was prominent in the region during the rule of the British Raj, which for Pakistanis, is reminiscent of the British Apartheid and the subsequent partition that forced many families to leave their homes.

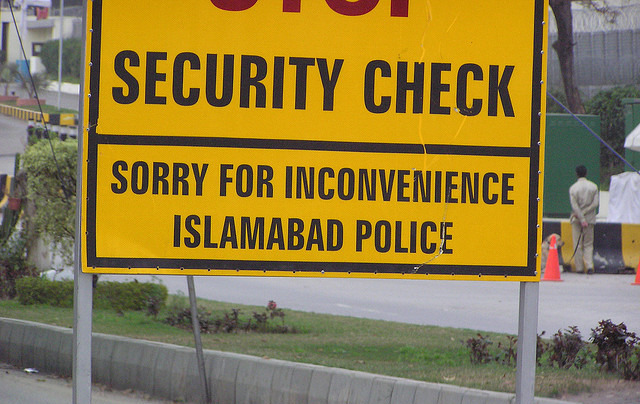

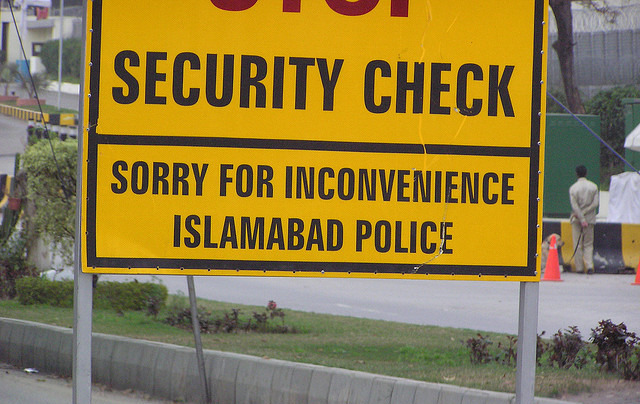

Eventually, talk of the restaurant’s policy reached the ears of Yasir Afridi, an assistant to the superintendent of the Islamabad Police. Afridi attempted to make a reservation and found that, true to the talk of the town, he would be unable to dine at ‘La Maison.’ Following his rejection, he led a raid on ‘La Maison’ and discovered over 300 bottles of un-registered liquor. Although Lafforgue claims that as a foreigner he is allowed to serve liquor to other foreigners, he is not under any diplomatic mission and is not operating a diplomat’s exclusive club, and therefore did not have the necessary licenses for his liquor cache. As of now, the restaurant has been shut down. However, Lafforgue has not given up yet, claiming that he will find a way to operate once again.