At age 12, a visit to the hairdresser marked a rare occasion for Umm Mohammad. “We were all very excited, as each girl had just been given a new, white dress.” And yet, the day didn’t proceed as expected. “Suddenly this man, who was really a stranger to us, started to undress us,” she told the German news organization Deutsche Welle. “Then he got out his razor blade.” Under no anesthesia and unhygienic conditions, Mohammad underwent an experience that would skew her perception of womanhood and traumatize her for the rest of her life. Her “circumcision” left literal and figurative scars that transcend the pain she experiences every day living in Cairo’s slums. Mohammad’s experience is but one narrative of the oppressed female experience in Egypt.

Among a myriad of other human rights violations, Egypt subjects 91% of its female population to genital mutilation, a procedure defined by a clitoridectomy, the cutting of the clitoris and external genitals, or infibulation, the sewing closed of the vaginal opening. Although the cultural practice is male-engineered, it’s most often propagated by mothers, who believe it to curb their daughters’ sexual desires and preserve their chastity. Above all, it maintains family honor and ensures marital prospects. However, these mothers are merely vehicles through which men establish a patriarchal dominance over women and deny them agency over their bodies and behavior.

Because many men spurn marriage to women who haven’t undergone some form of female genital mutilation (FGM), perceiving them to be “unclean”, mothers subject their daughters to the procedure in order to maximize marriage prospects. In this way, FGM has become a cultural practice for young girls as a critical right of passage into womanhood. However, it is men who have calculated this narrow definition of womanhood as a system of self-oppression. Men aren’t oppressing women; women are oppressing women. This ingenious and twisted system works in two ways: girls avoid pre-marital sex because they both fear the pain of breaking their stitching and the dishonor that comes with subverting a system that values honor above all else.

The practice, however, plays but one part in the female narrative around sexuality and honor. Every aspect of it caters to a man’s desires. Let’s consider infibulation, the sewing shut of the vaginal opening, which leaves only a small portion open for urination and menstruation. Many men physically prefer penetrating a woman who’s undergone the procedure; her first sexual encounter, and even subsequent times, will require him to literally rip her open. On a psychological level, the surgery allows men to claim women as property, which feeds into the cultural pressure for women to ‘save their chastity’ for their husbands. But, men are really stealing a woman’s agency over her own body; once that has been claimed, the woman often feels powerless. Yet, the practice doesn’t merely increase a man’s pleasure; it simultaneously decreases the woman’s by removing what many would argue is the epicenter of female sexual pleasure. Many women will never feel any pleasure, insinuating that female sexuality is of both shameful and secondary importance—even within the confines of marriage.

While many North African countries have yet to ban FGM as a practice, Egypt already has, which might indicate a turning of the tide. According to the UN, legislative steps towards punishing perpetrators are critical. Following the death of an 11-year-old during an FGM procedure in 2008, Egyptian legislators passed the Child Rights Law No. 126 to punish perpetrators with three months to two years of imprisonment—or a meager $700 fine. However, November 2014 marked the first time an incident reached trial. And, more discouraging, the rates of FGM haven’t changed significantly since 2008. This indicates a discrepancy between law and reality, which could be explained by Egypt’s political instability.

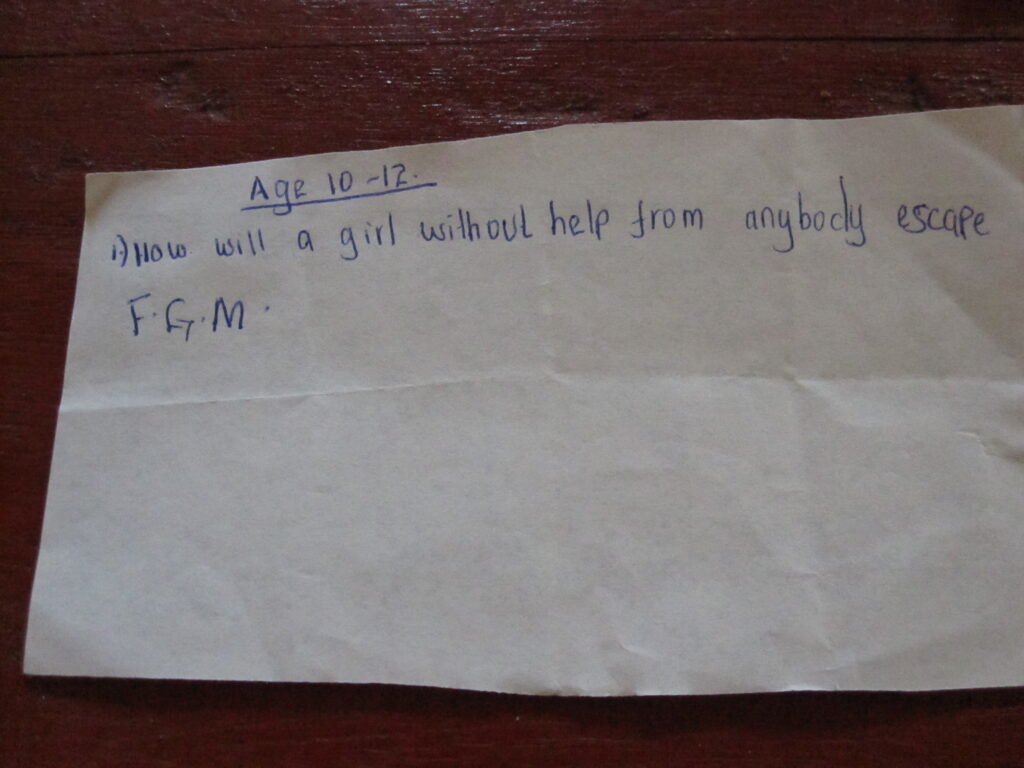

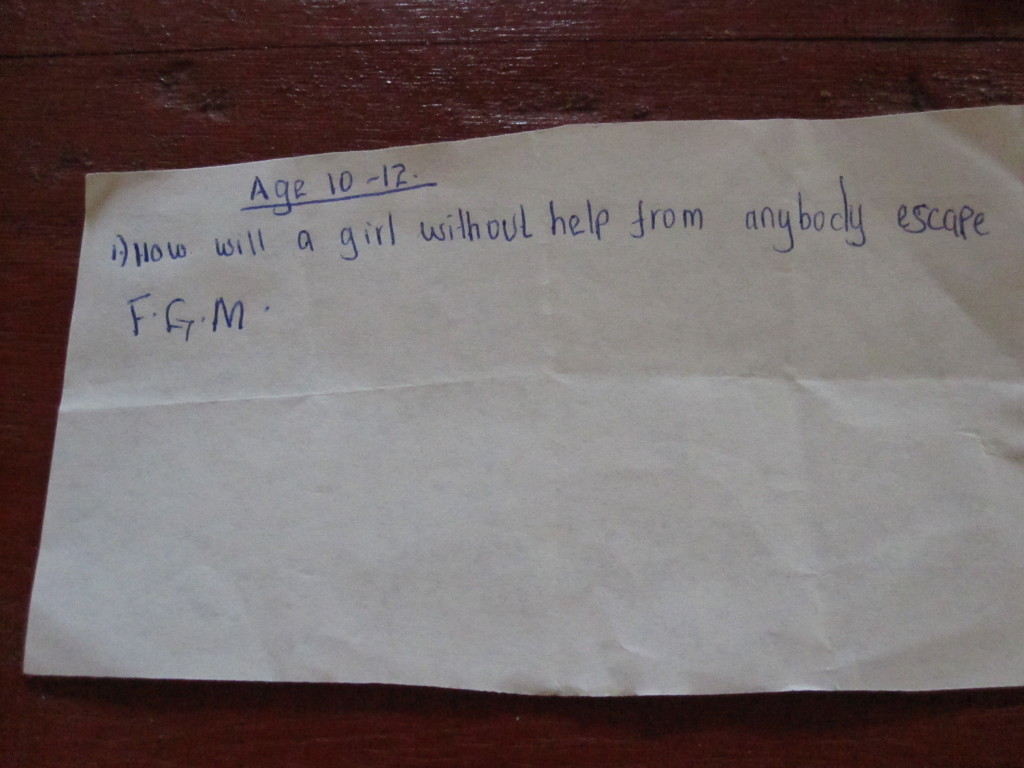

The Mubarak Regime prevented many medical professionals from conducting the procedure since they feared the repercussions of Suzanne’s Law, which outlawed FGM and liberalized divorce laws. No one had been prosecuted under his rule; however, in an attempt to obscure the realities of authoritarianism to the West, the Mubarak Regime gave women more opportunities to secure new freedoms. However, under ambiguous political authority, doctors now express a flagrant disregard for the law, willing to accommodate any family willing to pay the price. In fact, there’s been a drastic shift in those who actually facilitate FGM procedures. Egyptians are increasingly turning to medical professionals instead of local community members. Unlike many other MENA countries with ubiquitous female circumcision practices in which local village circumcisers or barbers perform the procedure, Egyptian doctors now conduct most operations—77% of them, in fact. Though this is a safer method than that which Umm Mohammad endured, it is concerning that doctors are willing to conduct a procedure with no medical benefits and a slew of physical and psychological risks. While engaging and educating local communities remains an important facet of combatting this savagery against women, it appears that directing law enforcement towards doctors might be more effective.

Within a convoluted system of authority and a burgeoning democracy, human rights need to be at the forefront of the public dialogue in Egypt. Women are especially vulnerable to abuse, especially under a cultural backdrop that perpetuates sexual violence. With a growing population of dissenters to the practice, it’s up to the government to enforce its codified laws against FGM, starting with prosecution and education of doctors. However, Egyptian women might have to wait a while to see their rights actualized, since it is unlikely that these changes will arrive under President al-Sisi, widely known for defending the “virginity tests” conducted on female protesters in 2011.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.