LOS ANGELES — While millions of children worldwide are returning to in-person learning for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, children from many developing countries have not been so lucky. And while most of these countries are still able to manage partial openings due to continuous struggles fighting the virus, many others have remained completely closed — and the situation remains bleak as the Omicron variant spreads.

In the Philippines, for example, a lack of access to vaccines — coupled with insufficient technology — has left many students with fragmented access to education. President Rodrigo Duterte emphasized his distress about the tedious vaccine rollout, comparing it to a “drought.”

“Rich countries hoard life saving vaccines while poor nations wait for trickles,” Duterte said. “They now talk of booster shots, while developing countries consider half-doses just to get by.”

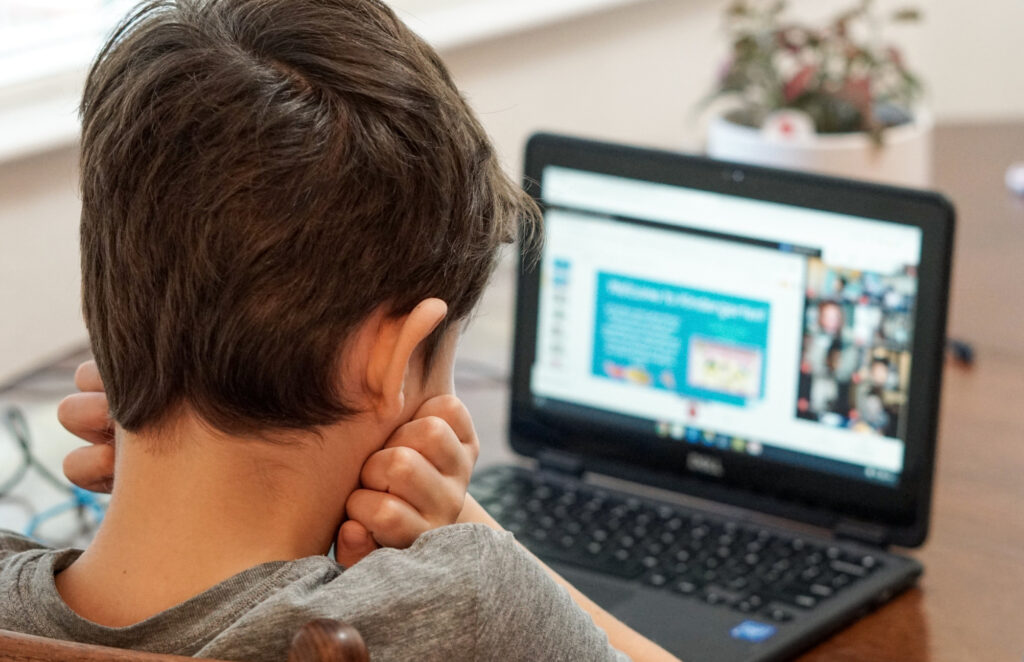

Duterte decided to keep schools closed to protect students and teachers from contracting COVID-19. The country currently has 45% of the population fully vaccinated, but its rates of vaccination are significantly slower than its regional counterparts. According to Stacy Kratz, an assistant professor at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, this is a global problem. Kratz said the choice to keep schools online comes with many obstacles in terms of technology.

“There’s the promise of decreasing the digital divide that we’ve been hearing about for 25 to 30 years — this promise that it’s going to be the great equalizer,” Kratz said. “But in the pandemic that equalizer has been disrupted and it’s really made evident who has privilege and who doesn’t from a global standpoint.”

According to research from the World Bank, about 60% of Filipino households do not have access to technology, making online education extremely challenging for students, parents, and teachers alike. While technology inequity has been a longstanding global problem, the situation is only exacerbated by COVID-19. Kratz said that even if students have access to devices to attend virtual class, although many don’t, there is still the inconsistency of internet access.

“You can have all the devices in the world if you don’t have the infrastructure for broadband it’s no good,” Kratz said.

She pointed out that in South Africa and India, for example, there are scheduled “brownouts,” times during which students and faculty don’t have any access to electricity. For students in South Africa, research found that in 2020, there was a learning loss of between 62% and 81% for students in the fourth grade.

While some schools in India remain fully closed, others have begun partial reopenings; however, access to technology has made online learning impossible for some students. When schools are operating on an online platform, nearly half of elementary and middle school students in India do not participate. In Nepal, for example, 70% of children do not have access to devices. Their quality of education cannot improve without the necessary infrastructure to ensure all students have the same education opportunities.

Data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control suggests that online learning is detrimental not only to students’ learning progress, but also to their socio-emotional development. This impact is exacerbated in communities where internet access is inconsistent. Kratz pointed out the effects that isolation can have on students.

“Isolation is rampant, of course, and that the impact across adolescence and into early adulthood is devastating for so many,” Kratz said. “And with that we see increased rates of depression and increased rates of anxiety.”

In light of increases in mental health issues, the stigma surrounding mental health as well as the lack of mental health service availability are barriers for many struggling students in the Philippines. Research finds that just 5% of the healthcare expenditure in the Philippines is given to mental health services. To put this into perspective, for every 100,000 Filipinos, there are approximately 0.4 psychiatrists.

Similarly, in India, mental health services are not easily accessible to everyone in need. Moreover, stigma surrounding seeking help runs rampant among teens and young adults. A survey conducted by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) found that only 41% of this age group in India approve of seeking help for mental health struggles. This number was extremely low compared to the results of various other countries that were surveyed. Dr. Yasmin Haque, India’s representative for UNICEF, emphasized the need for students to become more educated about the importance of mental health care.

“We need to break the stigma of talking about mental health and seeking support so that children can have better life outcomes,” Haque said. “For children who are isolated and traumatized, we must make sure there is better understanding [of mental health].”