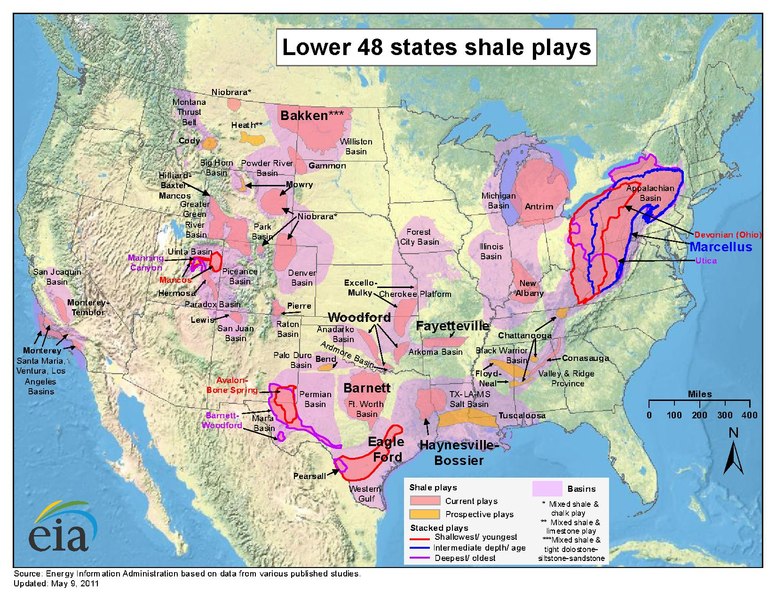

Current estimates for America’s resource endowment and extraction rates are very promising. Natural gas production is experiencing a momentous boom due to recent breakthroughs in unlocking natural gas trapped in shale. With these advances, shale gas production is forecast to increase from 42% of total U.S. gas production in 2007 to 64% in 2020. This level of growth is unprecedented, with the U.S. Government estimating there will be a 44% increase in total shale natural gas production from 2011 to 2040. With regards to oil production, the International Energy Agency predicts that U.S. oil production will rise to 11.6 million barrels per day in 2020, up from 9.2 million just a few years ago. This increase in oil production is orthogonal to trends in Saudi Arabia and Russia, which will see their production levels decline from 11.7 million to 10.6 million barrels and from 10.7 million to 10.4 million barrels, respectively. Leonardo Maugeri at Harvard has estimated that shale oil production alone could reach 5 million barrels per day by 2017. These statistics stand as a dramatic reversal from discussions in the energy community even 5 years ago when talk focused on declining fossil fuel reserves and the need to explore alternative forms of energy. Fossil fuels now dominate the energy game, and rightfully so.

While the macroeconomic benefits of America’s increased energy output are clearly tremendous, expectations for the average American consumer should be tempered. Though the price of natural gas has fallen in recent years due to our ability to tap into previously inaccessible shale reserves, the cocktail of booming transportation, a recovering economy, and rising exports have raised prices in the past year. In addition, the need for further fracking R&D is likely to drive costs up in the coming years. Shale oil is experiencing a similar phenomenon. Although the price of gasoline has fallen beyond global pricing levels in the U.S. for the short-term due to surging supply, the price of oil is determined on a global energy market and is projected to increase for the long-term as global demand continues to increase. The increased supply of natural gas and oil certainly has lowered costs for the American consumer for the time being, and will continue to do so when contrasted to an America without new-found energy reserves. However, Americans should not be expecting $2.00 per gallon gasoline prices anytime soon.

So what does this energy revolution mean for U.S. foreign policy? Many good things. America’s increased self-sufficiency will change the U.S.’ relationship with many other countries. Because of surging domestic supply, the U.S. will be less dependent on other nations for energy; in turn, this freedom will afford the U.S. greater flexibility in pursuing foreign policy interests because it will not be as constrained to secure energy resources abroad. Strategic relationships with nations such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are likely to change because there will be less of a need for their oil imports. Perhaps the U.S. will now be more forceful in advocating for democratic reforms within these non-democratic states now that it has greater autonomy on the energy front. In addition, the decreasing need to secure energy resources abroad may prevent the U.S. from becoming involved in regional disputes and conflicts to secure those interests.

America’s surplus of energy could also be an excuse for a more active role in foreign policy. America could gain more influence over other nations if U.S. firms are allowed to export energy resources. As we have seen in Europe, Russia’s domination of energy resources in Eastern Europe has enabled it to turn build new allegiances at the EU’s loss and expense. Consider the notable cases of Armenia and the Ukraine becoming part of Russian-led Eurasian Union. Please note that this author is not advocating for the U.S. to pursue an overbearing approach to energy exports like Russia, but rather a stable level of influence to help the U.S. realize its foreign policy objectives. If, for example, the U.S. could export to Central Asian states, it could gain more influence in the region and build a relationship that could allow these states to become closer to the West rather then being forced into a Eurasian Customs Union led by Russia. In a state like Japan, where natural gas sells for $17 compared to $3 in the U.S., greater exports from the U.S. could enhance a trade relationship with a major partner. Unfortunately, the U.S. is not reaping the benefits of energy exports because antiquated laws are in place that prohibit U.S. firms from exporting crude oil. In addition, the EPA has been very slow to grant export license requests for liquefied natural gas. These regulations are contrary to free market principles and concepts of free trade that America has advocated for since its inception. The U.S. government needs to allow U.S. firms to export and pursue their global energy interests more freely. The potential results of this policy change would provide more flexibility in U.S. foreign policy and would afford the U.S. even greater influence on the international stage.