On January 6, 2015, California officially began construction on the California High-Speed Rail system. The project is intended to link California’s major urban areas with an 800-mile rail network spanning from San Diego to Sacramento.

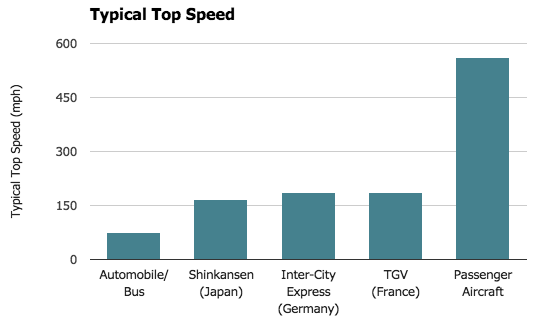

The project will be the second major high-speed rail project in the country, following Amtrak’s Acela Express in the Northeastern megalopolis. Acela trains, traveling at speeds of up to 150 mph, can traverse the distance from Washington, DC to New York in less than three hours. But unlike similar high-speed rail projects in Europe and Asia, Acela shares tracks with slower vehicles, consequently reducing its average speed to around 80 mph.

With dedicated tracks and speeds of up to 220 mph, the California High-Speed Rail project marks the US’s first significant attempt to build a network comparable to those of other developed countries. Sponsored by Governor Jerry Brown and his supporters, the project is seen as instrumental to modernizing the state’s transportation system. However, it has been a source of controversy since its approval as a ballot measure in 2008. Opponents criticize the plan’s $68 billion price tag and question the necessity and viability of high-speed rail in the US.

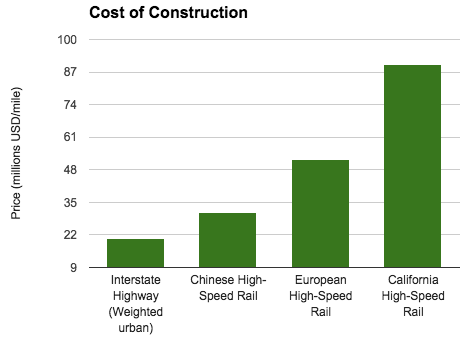

Cost of High-Speed Rail

The projected cost of California’s rail project equals $90 million per mile, far greater than the $52 million per mile average in Europe and certainly greater than China’s $31 million per mile.

The price of high-speed rail construction can vary dramatically depending on land value, terrain, cost of labor, volume of construction and other factors, but is almost always far more expensive than traditional expressway construction. When it comes to maintenance costs however, high-speed rail is only marginally more expensive.

Environmental Impact

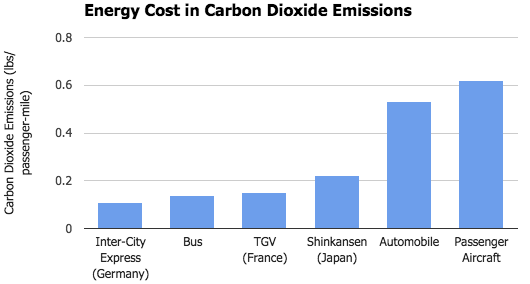

The case for or against rail infrastructure can usually be broken down into several major arguments. One such arguments relates to the relative eco-friendliness of each vehicle. The graphic below looks at the energy cost in CO2 emissions for several existing rail networks and various other modes of transportation.

This information was obtained through several important assumptions: (1) each high-speed rail system, bus and passenger aircraft operates at an average occupancy of 70%; (2) based on information from the US Department of Energy, the average automobile produces 0.85 pounds of CO2 per passenger-mile (23.08 miles per gallon) and uses gasoline; (3) the average automobile carries 1.6 passengers.

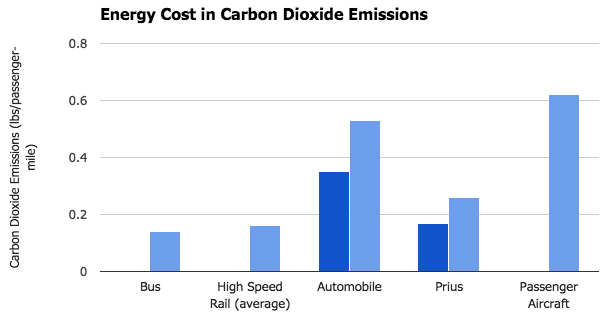

The graphic illustrates what one would imagine: high-speed rail, due to its economies of scale, is significantly more energy efficient than automobiles. High-speed rail produces around 0.16 pounds of CO2 per passenger-mile whereas the typical car produces 0.53.

But Randal O’Toole, an analyst at the CATO Institute and possibly the US’s leading critic of public rail projects, argues that cars engaging in inter-city travel usually carry more passengers. According to O’Toole, instead of using the average vehicle occupancy of 1.6 passengers (which is standard in many comparisons), a figure of 2.4 is more reasonable. By increasing the estimate by 0.8 passengers, the average occupancy increases by 50% and reduces the average energy cost to around 0.35 pounds per passenger-mile.

Moreover, future increases in the fuel efficiency of cars could lead to that number falling further. The Toyota Prius for instance, with 1.6 passengers, produces 0.26 pounds per passenger-mile. At 2.4 passengers, the number is even smaller: 0.17 pounds per passenger-mile.

With the average of the three studied rail networks being 0.16 pounds per passenger-mile, fuel-efficient cars with several passengers are fiercely competitive with high-speed rail in terms of eco-friendliness. Of course, few Americans own a Toyota Prius or a comparable vehicle, but the information suggests that investing in fuel-efficient vehicles may be a more cost-effective option.

Another important implication is that buses, with 0.14 pounds per passenger-mile, are just as, if not more, fuel efficient than high-speed rail. Inter-city bus networks, which require only the vehicles themselves and existing road systems to run, are likely the most cost-effective form of transportation. However, buses operate at low speeds and contribute to congestion and are thus often overlooked by planners as a major solution to inter-city transportation problems.

Economic Impacts

The potential benefits are not merely confined to high-speed rail’s energy efficiency. The speed at which it travels and its ability to quickly link cities together at such efficiency is a more important topic.

High-speed rail offers the fastest form of land transportation yet developed. High-speed rail can reduce the more than six-hour drive between San Francisco to Los Angeles to less than three hours. When the time spent at the airport is factored in, high-speed rail is typically faster than air travel for distances of up to 300 miles.

With reductions in travel time, supporters argue, comes economic benefits of increased productivity and reduced congestion. (Researchers at Texas A&M estimate that traffic gridlock in the US may waste as much as $87 billion per year in lost productivity and other economic costs.) Whether those economic benefits exist is difficult to measure and even harder to predict, but many experts argue that projects like the UK’s High-Speed 1 (HS 1) increase employment, rental rates and wages in cities along rail lines.

When it comes to proposed projects in the US, opponents are typically skeptical that high-speed rail lines will have sufficient ridership to be considered economical. For European lines, this problem has been largely absent. In Spain, rail transit accounts for more than half of the transportation volume between Madrid and Seville. Moreover, the construction of high-speed lines coincided with a 60% reduction in automobile traffic. While experiencing moderate declines in the midst of economic difficulty, most European lines, such as France’s TGV, witnessed large growth in ridership in the several years following their construction.

But in the US, as is often argued, the car-dependent structure of urban areas, or even factors as intangible as American culture, may inhibit passenger volume. In Europe and Japan, better structured transit systems and higher levels of urbanization make high-speed rail convenient and easily accessible. That the opposite is true in the US could easily limit the number of passengers accessing high-speed rail. But figures indicating that Amtrak recently achieved record ridership in 2013 coupled with projected increases, casts doubts on how important the current state of US transportation is in curbing future ridership. Additionally, experts on a University of California, Berkley panel predict that high-speed rail projects would encourage improvements in urban density and transit systems and thus enhance access to high-speed lines.

Conclusion

High-speed rail is hardly the cheapest mode of transportation, nor is it necessarily the most eco-friendly. However, it does offer potentially valuable solutions to congestion and economic problems in periphery regions along rail lines. Given their immense cost and uncertainty, high-speed lines in the US should be contained to the country’s several densely populated regions and should not be viewed as a perfect solution to transportation problems.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.