The Arctic represents an unknown. Old maps often label it Terra Incognita Septentrionalis: “Unknown Northern Land.” While it is now known that the Arctic is an ice-covered ocean, the region remains largely ignored in the realm of geopolitics. This is a mistake. There are tensions materializing over resource exploitation and opening trade routes to the tune of a rapidly changing climate that is disproportionately affecting the Arctic.

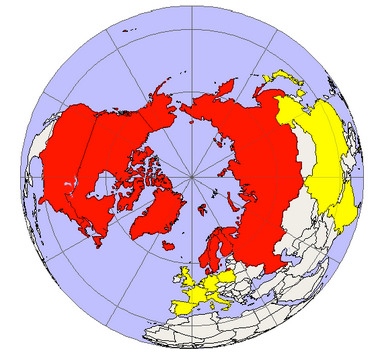

Arctic politics concern the geopolitical, economic, resource and environmental interests in the arctic region, in particular the governance of the Arctic Ocean. The only inter-governmental institution that explicitly governs this region is the Arctic Council (AC). Originally conceived to promote scientific research, the AC is comprised of the states that intersect the Arctic Circle: Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Canada, the US (by virtue of Alaska) and The Kingdom of Denmark (by virtue of Greenland). The AC’s directive is as both a governance institution for the creation of treaties and protocols relating to the environment, search and rescue, and more recently, shipping and resource exploitation.

In recent years, the AC has expanded its membership to 12 non-Arctic states by granting them observer status. These states are China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Netherlands, Poland, Singapore, Spain and the United Kingdom. Their interests lie primarily in the potential for trans-Arctic Ocean shipping routes and the extraction and exploration of the Arctic’s vast resources of oil (13% of the world reserves) and natural gas (30% of world reserves). The Arctic’s economic potential has attracted many actors who prioritize exploiting the land over preserving the environment via cooperative governance.

This October, India’s head of state, Pranab Mukherjee, made a historic first visit to the Arctic states. While he claimed that India’s interest in the AC “at the moment is scientific,” he never stated that the interests are not also resource, trade and geopolitically oriented. The Times of India, a leading Indian daily, had no reservations reporting the following about Mukherjee’s visit to Norway:

“India also does not want to be left out in the cold in the ongoing race among different countries to explore and exploit the vast reservoirs of oil and gas present in the region.”

This quote underlines the common thread of the top priorities states have in the Arctic—and the environment is not one of them. The mentality of seeing the melting Arctic as an opportunity rather than an ecological catastrophe is insidious on many levels. As the sea-ice melts, the exposure of dark ocean water that absorbs more solar radiation than white, reflective, ice will accelerate the melting process. Conservative models predict no Arctic Ocean summer ice by the end of the decade. Greenland’s freshwater ice sheet has undergone record melts for many consecutive years, and when it disappears, the ensuing sea-level rise will displace some 80% of the human population. Arctic permafrost will also continue to melt into rotting peat, thereby releasing additional greenhouse gases into the air, which may result in a runaway greenhouse effect. If observer states to the AC all have “scientific” interests in the Arctic, then why is climate science science seldom discussed?

While there continues to be a lack of meaningful, legally binding international treaties on climate change, the AC has passed a treaty on search and rescue operations in Arctic waters, and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has recently finalized its Polar Waters Operation Manual (PWOM). These steps, made in response to shipping vessels crossing the Arctic Ocean, will at least set a minimum standard for safety, navigational procedure, reporting and vessel specifications. Rather than protecting the Arctic from heavy ship traffic, policy-making institutions seem to be preparing for it. Is there irony in the fact that the European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellite mission to map Arctic sea ice is to better understand climate change as well as to ease trans-arctic maritime navigation?

Oil and gas prospects have attracted international oil companies from several nations to descend on the Arctic. STATOIL, Gazprom, Rosneft and Lukoil, Exxon, Total and Royal Dutch Shell are just a few of the big oil industry players in the region. Sometimes, as with France’s Total, it is unclear whether it is the state or the company that dictates policy. Indeed a report from French Daily Le Monde points to how Total plans on shifting the majority of its operations to Russia by 2020. Also, upon the accidental death of Total’s CEO, Russian President Vladimir Putin extended sincere condolences, reportedly writing: “We have lost a true friend of our country.”

Table: Oil Companies Exploring in the Arctic (partnership with Russian Oil Company †, AC member *, AC observer **)

| Company | Nationality |

| Rosneft | Russian Federation * |

| Statoil † | Norway * |

| Exxon † | USA * |

| Royal Dutch Shell † | Netherlands **, UK ** |

| Total † | France ** |

| Agip † | Italy ** |

| Gazprom | Russian Federation * |

| Lukoil | Russian Federation * |

| BP † | UK ** |

| EnCana Corp | Canada * |

| Armstrong Oil and Gas | Canada * |

| Conoco | Canada * |

| ENI † | Italy ** |

| Repsol | Spain ** |

| PGNiG | Poland ** |

| JOGMEC † | Japan ** |

| CNPC † | China ** |

| ONGC † | India ** |

| Wintershall | Germany ** |

Considering that for many of these states energy security is tied to national security policy (like in the US) it is to be expected that corporate interests have significant leverage in policy making. It is the link between oil and security that is taking precedence over the link between environmental preservation and security in Arctic Policy. The National Strategy for the Arctic Region, an opaque 11-page US State Department policy document, includes this paradox as a key item of the first section of the US “Lines of Effort” portion:

“The Arctic region’s energy resources factor into a core component of our national security strategy: energy security. The region holds sizable proved and potential oil and natural gas resources that will likely continue to provide valuable supplies to meet U.S. energy needs.” (National Security Strategy, May 2013).

The document also claims environmental stewardship as a high priority, leaving one to wonder: how could both priorities realistically coexist in a policy document for the US government that is only 11 pages long? Given that the US is scheduled to take over AC chairmanship from Canada in 2015 (chairmanship rotates after each 2-year term), the prominent narrative is that the AC will continue to be an institution plagued by identity crises and a lack of meaningful leadership.

Among the AC states, Russia is the most aggressive. The reasons for this are manifold. For one, Russia has the longest coastline on the Arctic Ocean. Additionally, the Russians claim, under UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS) Article 76, that a significant portion of that ocean is theirs by geological right. The ability to project power rests Russia’s large, albeit outdated, icebreaker fleet.

There is very little to prevent Russia’s aggressive moves in the Arctic; they are filling a power vacuum. Suddenly, the menaces made by Russian military aircraft, such as simulated bombing, against neutral Arctic states, like with Sweden in October, take on a new light. Can Russian Foreign Ministry assurances that the re-militarization of the Arctic region is nothing to worry about, as well as promises to resolve disputes through dialogue, be taken at face value?

If the geopolitical situation remains unchanged, then Russia will continue to name oil fields “Victory” and the pressing environmental issues will continue to be ignored—especially considering that the US’s current voice in the AC, Alaska, “identified its top Arctic Council priority as “creating jobs,” followed by “suicide prevention.” Climate change did not make the list.

Consider that: “climate change did not make the list.” This week, world leaders are meeting in Peru to address the global threat of climate change. Reporting on the negotiations, the New York Times quoted concerned climate scientists: “At stake now, they say, is the difference between a newly unpleasant world and an uninhabitable one.” For two decades, the UN has failed to create a pact on climate change. If negotiations fail on a global level, then it is imperative to create policy on a regional level.

The Arctic is a ground zero for climate change. There, the effects are more sharply observed: consider a 5°C average temperature rise versus the global average of 1-2°C. The AC has the potential to set an example for international environmental stewardship, and the ability to create informed policy due its scientific research arm. It is up to the AC states to set aside geopolitical and resource-driven interests; if this cannot happen in the Arctic, then whatever happens in Peru may be inconsequential. The Arctic is simply too important to the regulation of the global climate.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.