By Alex Melnik

The Rohingya people of Myanmar face some of the world’s most oppressive conditions, yet receive little international attention. Hundreds of thousands have fled to neighboring countries to seek asylum, with many dying en route. To prevent further human rights violations, the US must take more serious actions.

When the word “refugee” is mentioned, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? For Americans, it’s probably the Syrian Refugee Crisis, a tragedy which has resulted in over 5 million refugees and another 6 million internally displaced persons. The term “drowning at sea” may also convey similar imagery, particularly the drowning of a Syrian children in the Mediterranean Sea, or perhaps the other failed attempts of asylum seekers on dangerous boat journeys.

Unfortunately, a similarly disturbing crisis on the other side of the world has been largely underreported in American mainstream media. This is the Rohingya Refugee Crisis, which the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations has termed a “forgotten crisis.”

So where does the US come into play? In 2014, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution on persecution of the Rohingya people, urging the Burmese government to stop the persecution and discrimination of minorities within its borders and calling on the international community to put pressure on Burma (Myanmar). The US has also taken in about 13,000 refugees from Myanmar in the past 15 years. Since this resolution, however, the US has done little else, and human rights violations have persisted.

To get up to speed with the crisis, read the answers to six important questions below.

Who are the Rohingya?

The Rohingya are an ethnic minority group in the Rakhine state of Myanmar. The Rohingya are Muslim and speak the Rohingya language, whereas the Rakhine ethnic majority speak the Burmese language and are Buddhist. There are a total of 800,000 Rohingya living in the Rakhine State, making up around two-thirds of the state’s population. The Rohingya’s origins can be traced back to the 15th century, when Muslim traders immigrated to the region.

However, Rohingya is largely a self-identified term in Myanmar, as the government does not recognize it as one of its official 135 ethnicities. Rather, the Rohingya are largely considered as Bangladeshi illegal migrants. In fact, a 1982 Citizenship Law stripped them of their citizenship, as well as the rights associated with it; Rohingya must obtain permission to marriage or work, are restricted on the number of children they may have, and cannot vote. They are not even included in the national census. Not surprisingly, the Rohingya have been called “the most persecuted people on Earth.”

What is the Current Situation?

In recent years, persecution of the Rohingya has intensified. The Rohingya must endure institutionalized systemic discrimination due to government policies that restrict almost every aspect of their lives. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, 78% of those living in the Rakhine State live below the poverty threshold.

They lack almost any official recognition. Although a 2014 national consensus backed by the United Nations permitted the Rohingya to self-identify with that term, Buddhist nationals protested, threatening to boycott the census. The government then reneged and decided Rohingya could only identify as “Bengali.”

Violence has also broken out between the Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine people. In 2012, for example, riots broke out when several Rohingya men were accused of raping a Buddhist one. This led to riots and mass destruction, with over 2,000 homes destroyed and the displacement of over 140,000 people.

Attacks on the three guard posts on the borders between Bangladesh and Myanmar in 2016 resulted in additional ethnic conflict, as the attacks were blamed on Rohingya militants. Tens of thousands more Rohingya were displaced, and many more homes were destroyed.

Why are the Rohingya Persecuted?

The Council on Foreign Relations, a US think tank focusing on US foreign policy, provides a good explanation:

Widespread poverty, weak infrastructure, and a lack of employment opportunities exacerbate the cleavage between Buddhists and Muslim Rohingya – Council on Foreign Relations

An example that illustrates this is protests in 2014 by the Buddhist majority over concerns that humanitarian aid was only going toward the Rohingya. However, conflict here cannot only be understood in terms of economics and competition. Much of the discrimination goes back to the idea that Rohingya are not citizens of Myanmar, but rather illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. This view is strengthened by the fact that this is codified in law. As Rohingya are not included in the national census, it as if they do not even exist.

Where Are They Going?

The Rohingya began migrating to Bangladesh in 1978, but their first major wave occurred in 1991-1992. Currently, there are two official UN Refugee Agency camps in Bangladesh, with a total of 33,000 people. However, between 300,000 and 500,000 Rohingya live elsewhere within the country. While those inside the camps are recognized as Rohingya, the others are not afforded any legal status, and are rather seen as “undocumented Myanmar nationals.”

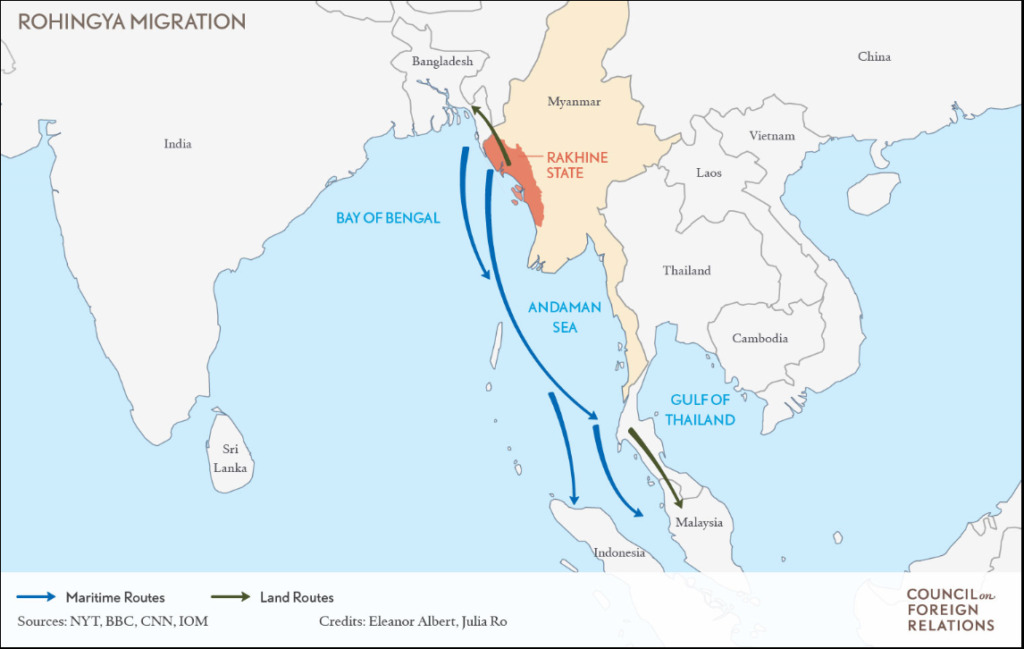

The Rohingya have also fled to Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and even the Philippines, often via a treacherous boat journey. Previously, many were trafficked by land through Thailand, but after recent crackdowns on human trafficking by the Thai government (as a result of pressure by the United States), much of the trafficking has shifted to sea routes instead.

Sadly, human traffickers often take advantage of the Rohingya and have abandoned them at sea, resulting in stranded refugees. Countries in the region have not been too willing to help, only doing so after much international pressure.

According to the International Organization for Migration, more than 88,000 migrants fled by sea between January 2014 and May 2015. However, some of these migrants were actually from Bangladesh, which created political complications, as the Bangladeshi migrants were fleeing for economic reasons, whereas the Rohingya were fleeing from persecution (as well as economic hardship, largely caused by this very persecution).

What’s Being Done So Far?

Not too much, unfortunately. Myanmar’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, who is seen as a champion of democracy after enduring over 15 years of house arrest and leading the National League for Democracy Party to victory in the first free election in 25 years has been largely silent on the issue, refusing to speak publicly about it. Her spokesperson has also denied allegations about human rights abuses. However, Suu Kyi, who is a Nobel Peace Prize Winner, recently established a commission led by Kofi Annan, a former United Nations Secretary-General; the Peace and Reconciliation Commission will have a report ready in August of 2017.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which is composed of 10 Southeast Asian nations including Myanmar, has not produced a unified response either. This is largely because ASEAN lacks established legal frameworks, and its human rights branch, the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission Rights, lacks any real power. In addition, ASEAN is consensus-based, meaning every country must agree.

On March 17, China and Russia blocked a potential press release from the UN Security Council which would have “noted with concern renewed fighting in some parts of the country and stressed the importance of humanitarian access to all affected areas.”

The European Union also recently called on the UN to send a fact-finding mission to Myanmar to investigate allegations of human rights abuses against the Rohingya.

With Myanmar and ASEAN staying largely uninvolved, the brunt of the work has fallen on non-governmental organizations, such as Human Rights Watch.

What Else Can Be Done?

A single, simple solution does not exist. Rather, the international community must work together to further expose human rights violations and pressure Myanmar to change its ways.

In terms of the US, The Council on Foreign Relations suggests that it “lead an international effort to find a humane solution.” This would involve a fact-finding mission, as called for by the EU, to assess the true amount of human rights abuses that have occurred. It would also mean a willingness to accept more refugees. While President Obama lifted sanctions against Myanmar so that the US could take in more Rohingya refugees, it’s unlikely President Trump will be very willing to take further action.

Instead, it will likely be up to ASEAN to take a stronger stance. But is this political will there? Given that three of its members, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei Darussalam are all Muslim-majority countries, the hypothetical answer is yes. But only time will tell if ASEAN will actually take any concrete action.

While action at a federal level may not be plausible in this administration, Americans can still make a difference*. By starting conversations about this issue, supporting NGOs, signing petitions, and more, we can ensure that the Rohingya Crisis does not remain “forgotten.”

*This article provides great information about specific actions we can all take.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.

Alex Melnik is a junior at the University of Southern California majoring in International Relations and pursuing a Progressive Master’s in Public Administration. He spent the past year abroad in Indonesia via the Boren Award and Critical Language Scholarship. He has also interned in Taiwan in the past.