Recent geopolitical events in Africa have shed light on an unfortunate trend in Western media: the neglect of substantial African stories. When stories on Africa do make headlines, they are usually the most sensational pieces. These pieces reveal two unfortunate tendencies by the Western media: one, the portrayal of Africa as one geopolitical bloc; two, the portrayal of Africa as little more than a disaster-ridden continent. To learn more about this harmful pattern and its causes, I spoke with Dr. Cheikh Anta Babou, a professor of African history and the history of Islam in Africa at the University of Pennsylvania.

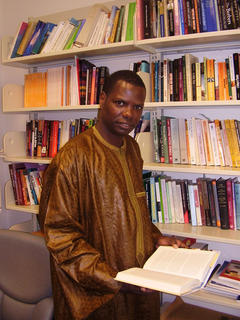

Dr. Babou, a native of Senegal, joined Penn’s history department in 2002 and now teaches courses entitled Africa Before 1800, Decolonization and Africa, Religion and Colonial Rule in Africa, and Islam and Society in America. His research focuses on mystical Islam in West Africa, as well as the new African diaspora. Dr. Babou’s articles have appeared in African Affairs, Journal of African History, International Journal of African Historical Studies, Journal of Religion in Africa, Africa Today and other scholarly journals in the US and France.

GLIMPSE: It seems that Western news outlets cover only the most sensational stories out of Africa. Boko Haram, Ebola and Somalian pirates make mainstream news in the US, while things such as the Nigerian elections and the Central African Republic crisis aren’t covered. Why does this pattern exist?

BABOU: The coverage of Africa is crisis-driven. This pattern has roots in the past, specifically in the tradition of Africa’s being perceived by Westerners as the bottom of the ladder. You also have to deal with the problem that always exists with the media, which is that news outlets publish stories that people want to read. There simply isn’t enough demand in the US for African stories. When people think about Africa, they think of crisis, war and disease. That’s what comes to mind when you hear the word “Africa”. There are too many good things happening that you don’t hear about.

GLIMPSE: What are some recent examples?

BABOU: There are two things that come to mind. First, you have the elections that happened two weeks ago [January 20] in Zambia. Michael Sata [the incumbent president]died in office and was replaced via a peaceful and democratic election. The election was tight and the winning candidate [Edgar Lungu] won by a small margin. Power was transferred peacefully. The second example isn’t as recent: in 2007, Senegal also had a successful multi-party election. Again, these events don’t receive wide publication as do elections in European countries.

GLIMPSE: It seems that the success of the democratic process is something we take for granted in the US.

BABOU: It is. In Burkina Faso last year, the president [Blaise Compaoré] tried to manipulate the constitution and run for a third term. The people rose up and protested throughout the country, putting so much pressure on him that he was forced to resign. In the Republic of Congo, the same thing just happened. [President] Joseph Kabila tried to amend the constitution to consolidate his own power, and protests also ensued across the country. These were great moments for Africa, great moments for democracy. Africans took control of their own destiny in these countries and didn’t call on Europeans for help. They took charge and democracy happened the way it’s supposed to. But again, these are stories that you don’t hear about in the US.

GLIMPSE: What about Africa’s growing middle class? That issue seems to be covered in the West.

BABOU: Sometimes you’ll hear from the business world or the academic world that Africa is experiencing economic change or economic progress. There is a theory that Africa is the world’s next great frontier. The growing middle class of economically mobile Africans, the increasing GDP of African nations, the anti-corruption efforts of governments and an occasional economic referendum—these are all things that represent change and movement in Africa. But when an African government bolsters its economy or develops its infrastructure, American news outlets do not find an interesting story. As I said before, people are interested in the unusual parts of Africa—the parts that scream “not us” to the Western world.

GLIMPSE: Some of the improvements that you listed are truly pivotal for African countries.

BABOU: Yes, and the best thing about it is that these changes are happening not because former colonial powers are willing them, but because the African people are willing them. Even compared to the US, this growth is superior. In the US, we still have the issue of the 1% and the 99%. There’s no movement like there used to be. In Africa, though, there is popular demand for these things. More people are paying attention to how their tax money is used and they’re responding if that money isn’t being used appropriately.

GLIMPSE: What other issues do you think should receive more Western coverage?

BABOU: The World Cup captures the attention of people around the world every four years, but few people outside of Africa follow the continent’s major soccer tournament, the Africa Cup of Nations. The Cup, which is going on right now, is held every two years and has become very popular. The youth are mobilized because of it. Similar to the World Cup, countries that haven’t been able to make economic or political inroads can do well in the tournament. The special thing about this year’s cup is that even countries that were engulfed in the Ebola crisis are participating. Guinea, for example, has been plagued by Ebola – almost 2,000 people have died – but still sent a team to the Cup. The entire continent is mobilized.

GLIMPSE: What can we as journalists do to increase news coverage of Africa in the US?

BABOU: That’s a tough change to bring about. You can’t forget that news making is a business; it’s about making money. One thing I’d like to see more news outlets do is bring on more African correspondents. I was just reading an editorial piece in the New York Times responding to many people’s concerns about coverage of Boko Haram. When this year’s unfortunate events in France took place, the Western media responded with a huge amount of coverage. Around the same time, Boko Haram killed an estimated 2,000 people in Nigeria and the Western media gave it minimal coverage. Many readers expressed their frustration with this inequality, and the editor responded by explaining that the Times has only one correspondent for all of West Africa. If you have only one person trying to cover that large a region, where so much is happening, how can you expect to cover important issues?

GLIMPSE: What sources of news do you follow for coverage of important African issues?

BABOU: Unfortunately, to receive good news about Africa, you have to go through former colonial outlets. Radio France Internationale and BBC do a good job. BBC in particular has reporters on the ground, people from Africa, who report almost every day. It’s contextual news. Al Jazeera also does a good job, much better than CNN, whose coverage of Africa is superficial. I don’t even think that CNN has a correspondent physically in Africa—this person might fly from Europe and spend 48 hours in Africa when something “newsworthy” happens. Former colonial powers still have a stake through European expats living in Africa. These people are highly interested in what’s going on and often contribute to good coverage like BBC’s.

GLIMPSE: It probably doesn’t surprise you that CNN still hasn’t published a major story about the ceasefire in South Sudan, even though it’s been over 24 hours [February 2].

BABOU: You will rarely find an African piece of news among the first stories of any major news outlet in the US.

GLIMPSE: Unless it’s Ebola.

BABOU: Exactly. Ebola does have to be part of the story, though. When it was incubating in Guinea, it wasn’t covered. But when an American aid worker got infected, it became an American story and people talked about it and worked themselves into a frenzy. All the while, people in Guinea were dying. Entire villages were being wiped out but no one was talking about it. Once the aid worker was cured and the scare on US soil died down, the coverage stopped entirely.

GLIMPSE: Liberia just got the figure for new confirmed cases per week under 100, but the American media didn’t circulate that story either.

BABOU: Mali, Nigeria and Senegal have also been successful in stopping the spread of the disease. They contained it, but you don’t hear about those successful stories. You only hear about the cases where it’s running amok. That’s just what people in the West too often associate with Africa – things going wrong. That’s the heart of the problem. When there’s good news in Africa, it’s just not interesting to people.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.