INTRODUCTION

Nearly ten years after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement officially ended the bloody Sudanese Civil War, South Sudan is again on the brink of disaster. Months of negotiation following a tenuous peace deal between President Salva Kiir and former Vice President Riek Machar collapsed in July, when forces clashed on the streets of the capital city Juba for several days. In the months since, a brewing humanitarian disaster has reached catastrophic levels of food insecurity and created millions of refugees while the government cracks down on platforms for news and political dissent. On November 11th, the popular radio station Eye Radio was shuttered by security officials with no official reasoning, and in September, authorities similarly closed the Nation Mirror newspaper without providing a reason. Adama Dieng, United Nations Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide, visited South Sudan and reported: “I saw all the signs that ethnic hatred and targeting of civilians could evolve into genocide if something is not done now to stop it.”

Today’s struggle is a vicious zero sum game – a battle for power between the political and military elites who exploit the long-running history of conflict in the region, depriving citizens of basic necessities such that ordinary people believe that their survival depends on pledging loyalty or support. With no end in sight, South Sudan’s current situation reflects its legacy of violence and highly fragmented internal state, as well as its origins born out of a bloody war with northern Sudan.

A LEGACY OF VIOLENCE

Civil war raged between the North and South for almost 40 years (1955-1972 and 1983-2005). After the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005 and referendum for independence in 2011, South Sudan became the world’s newest country – as well as one of its least developed. After decades of conflict, South Sudan faced the formidable task of developing basic infrastructure, human capital and formal civilian institutions.

Pre-occupied with state-building failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. and larger international community lavished $1.4 billion dollars of aid onto the apparent poster-child for Western conflict resolution. However, the carrots came without a stick. With little oversight or aid conditions, the money rarely found its way into infrastructure projects or public services. The advice of hundreds of international consultants sent to South Sudan was ignored. At the time of independence, South Sudan had an estimated 11.6 million people, including the Dinka (35.8 percent), Nuer (15.6 percent), and in descending size, the Shilluk, Azande, Kakwa, Kuku, Murle, Mandari and Didinga minorities. While ethnic tensions were relegated to the background during battles with the North, they returned soon after independence, and the West failed to pressure and bring together these estranged communities. The government was inefficient, incompetent and unable to enforce bureaucratic order in the country. Institutional gaps, a failure to meet citizens’ expectations, and a collapse of mechanisms made it clear that the government was incapable of fulfilling its promises. The corruption-security nexus was exacerbated by the fragile public institutions which were too weak to manage resources, enforce government transparency or maintain checks on abuses of power.

Public expenditure in South Sudan was 8 to 9 times higher than Ethiopia’s and 5 times higher than Uganda’s. Yet there was little to show by way of improvements in education, public health or infrastructure. The only thing that grew was the gap between the newly rich and powerful corrupt officials and the impoverished citizens who had nothing; “Instead of creating institutions that deliver services and ensure the rule of law, and ignoring systemic checks and balances, leading members of the factions united momentarily to create a parasitic system in which mass corruption and the brutal maintenance of power became the raison d’etre of governance.”

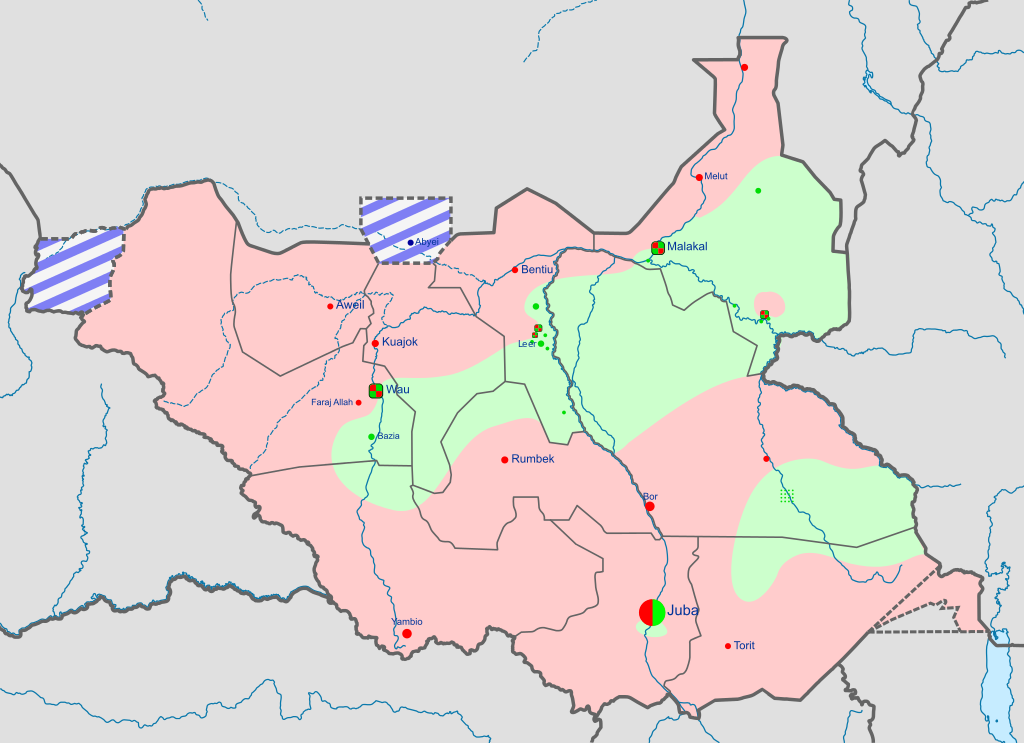

In December 2013, accusations of a coup plot against the state, months of mounting political tension between President Kiir and Vice President Machar, inefficient financial institutions and widespread perceptions of corruption culminated into a bloody civil war. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), long seen as the symbol of national unity and sovereignty, was subsequently divided primarily along ethnic lines either in support of President Kiir (the Dinka) or Vice President Machar (the Nuer). Although the Dinka are the largest ethnic group in South Sudan, they do not make up the majority of the population. The Dinka have long dominated politics and have been accused of monopolizing top posts. That sentiment was exploited by Machar as he declared a rebellion with the support of several senior Nuer military commanders, effectively invoking an ethnic conflict.

Awash in arms from decades of armed conflict, South Sudan’s rural citizens formed militias along ethnic lines. With no apparent national civic identity or strong basis for a stable state, political identity in South Sudan has defaulted to ethnic identity; the militias are essentially ethnically based armed units, mobilized by ethnic narratives of fear and legacies of violence, which were exploited by Kiir and Machar.

CONTINUED STRUGGLES

Since 2013, continued fighting has displaced more than 2.7 million people, including 200,000 sheltered at U.N. bases throughout the country. Various negotiations under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) finally led to an international peace agreement in August 2015. Kiir signed the deal a week after Machar, expressing his concerns and calling the agreement divisive and an attack on South Sudan’s sovereignty. Although the agreement was signed in August 2015, the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGNU) was not formed until April 2016. Former Vice President and opposition leader Riek Machar returned to Juba for the first time since the outbreak in 2013, and was sworn in as the First Vice President of the new power-sharing government under President Kiir. By June, however, the agreement had seemingly collapsed and hundreds were killed before ceasefires were declared on July 11th. Both sides of the civil war have been accused of mass rape, massacre, and the use of child soldiers. Both sides have been exploiting South Sudan’s natural resources. President Kiir’s wife and children own stakes in the oil and mining sectors, while Machar has been selling oil futures for weapons.

South Sudan is now classified by the United Nations as a “level 3” humanitarian disaster – one of only four in the world, alongside Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. A crippling hunger crisis affecting an estimated 4.8 million people is reportedly so dire that some refugees living in swamps are surviving on water lilies and goat bones. Food costs have skyrocketed since fighting began in July, and in the capital of Juba, vegetable traders now cut tomatoes in half to sell because some customers cannot afford a whole tomato. The World Food Program’s main warehouse in Juba was reportedly looted by government soldiers in July, losing 4,500 metric tons of food which would have fed 220,000 people for a month. As of October 2016, an estimated 2,500 refugees – mostly women and children – were crossing from South Sudan into Uganda every day. Most live in settlement camps, where resources are limited and families have been living on partial food rations. An estimated 200,000 South Sudanese refugees have fled to Uganda since July, and according to the UNHCR, there are now 54,000 registered South Sudanese refugees in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Out of the UNHCR’s pledged $251 million South Sudan refugee plan, only $48.5 million has been received.

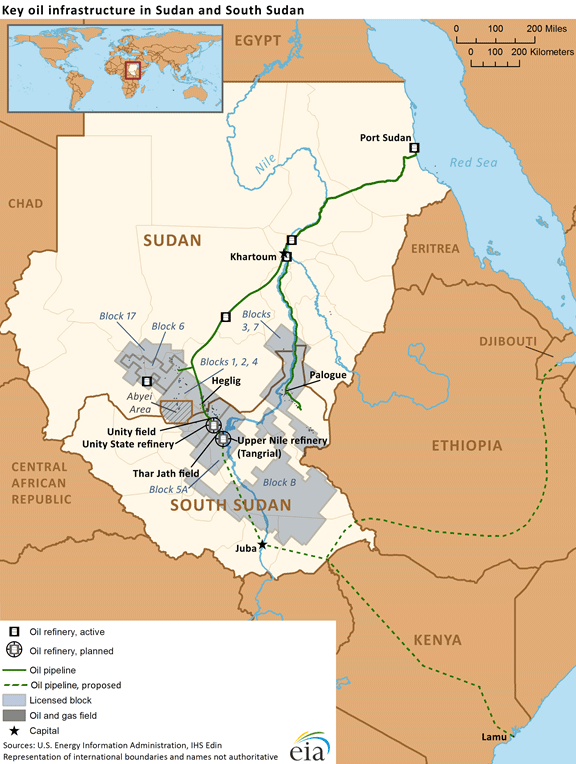

The economy is in shambles. South Sudan is the size of France yet has only 200 kilometers (125 miles) of paved roads. This is a serious inhibitor to not only delivering aid, but also to developing any sort of self-sustaining industry. Inflation is at 835.7 percent – the highest in the world. South Sudan is an oil income-dependent country, and until independence, South Sudanese oil fields produced 75% of Sudanese oil and sold it through Sudanese oil transport infrastructure. Now that infrastructure is monopolized by Sudan. In 2014, total oil revenue was reportedly $3.38 billion, of which the government only received $1.71 billion after $884 million in transit fees to Sudan and $781 million in loan payments. A 2016 IMF visit determined that South Sudan would receive no oil revenue if it were to meet its obligations to Sudan; negotiations are currently ongoing to reschedule delivery dates. The low global price of oil, combined with rampant inflation, drastically rising food costs, and the extreme shortage of hard currency have put severe strains on the economy.

Furthermore, the United Nations has catastrophically failed to fulfill its responsibilities. It has failed to protect both civilians and humanitarian workers; South Sudan had more attacks on aid workers than any other country last year, and at least 57 aid workers have been killed since 2013. Despite a large presence of around 12,000 U.N. Peacekeeping forces, a horrific gang rape of aid workers by government troops in a hotel less than a mile from a U.N. compound went unanswered, even as the victims frantically called for help. In late October, a U.N. inquiry accused the UNMISS of failing to respond to the attack; in response, Kenya began pulling its Peacekeeping troops out of South Sudan. Almost 200,000 South Sudanese reside in U.N. Protection of Civilian (POC) sites – refugee camps for the displaced that are secured by peacekeepers at or near their bases. The camps were never intended for large, long-term settlements, and are overcrowded with terrible living conditions. In 2015, a UN human rights commission found that the situation in South Sudan demonstrated “new brutality and intensity,” with “a scope and level of cruelty” that “suggests a depth of antipathy that exceeds political differences.”

THE PATH FORWARD

The complexity of the situation proves there will be no easy solution anytime soon. Although the conflict began with a political dispute, it will not be resolved simply by reconciling rival political factions. South Sudan’s history of ethnic manipulation for elites’ own political and economic benefit continues to challenge the feasibility of social cohesion in the country, and there is little evidence that President Kiir’s government is willing to share power with the opposition. Increasingly antagonistic rhetoric against the UN and international groups pose threats not only to peacekeepers, aid workers and expatriates, but also to the viability of continued operations within South Sudan. Furthermore, aid donors are hesitant to take policy stances that could threaten the ability of aid agencies to deliver relief in the midst of humanitarian crisis. The efficacy of piecemeal technocratic solutions is dubious without an accountable, functional government in place. There are, however, a few critical first steps that must be taken for any long-term solution to materialize.

- Stop the meddling of regional actors. The interference of neighboring countries and their national interests has played a destabilizing effect, from Sudan to Uganda to Kenya to Ethiopia. Sudan has failed to demonstrate commitment to the terms of the CPA, as evidenced when they prevented the residents of Abyei (which continues to be a hotly contested region) from participating in the referendum. In 2012, the South Sudan government, angered by border disputes and negotiations over oil transit and export to the Port Sudan terminal in the North, suspended oil production for over a year, and oil production continues to be a critical area of contention. With so much at stake in resource-rich South Sudan, the continued meddling of outside actors obstructs not only internal stability, but also forces the rival factions to compete with one another for foreign funding and support. The U.S., U.N., and other international allies must show that the overarching goal of bringing peace and stability to the region should be regional actors’ foremost priority and is beneficial for all. Once this is done, South Sudan needs to negotiate resource-sharing or access agreements with all its neighbors.

- The aid agencies must leave. Not only have the aid agencies failed to protect citizens and their own workers, most significantly, they have been severely hindered by forces on both sides. It can be argued that aid agencies, especially food agencies, are keeping a larger humanitarian crisis at bay. Yet, as Dambisa Moyo argues in “Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa,” halting aid delivery will force actors to be accountable for the plight of their supporters once it is clear that outside aid is what is keeping the country afloat. It will also force actors to promise and provide conditions stable enough for aid agencies to carry out their missions.

- President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar both must step down. International questions about the status of the peace agreement and legitimacy of the TGNU have persisted following President Kiir’s replacement of Machar and other opposition representatives in late July. The faith of the population in the current government is dubious at best, and much like the debate over President Bashar al-Assad in Syria, a fundamental disagreement over the governance needed to unify a fragile state divided down ethnic lines is one that can only continue with new leaders in both parties. The U.N. Security Council has already blacklisted six generals – three from each side of the conflict – under a targeted sanctions regime, and on November 18th, the U.S. proposed for Machar, South Sudan army chief Paul Malong and South Sudan Information Minister Michael Makuei to be added to the list.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.