Guest Contributor: Ajoy Thamattoor

Nepal is a crucible where a new experiment in pluralistic, secular democracy is being forged. Though overshadowed by its neighbors India and China, and riven by poverty and social, economic and linguistic divisions, the country’s current political transition is leading Nepal toward a society that shares in Western political values. The democracies of the West should note this shift and invest in Nepal’s political and economic future.

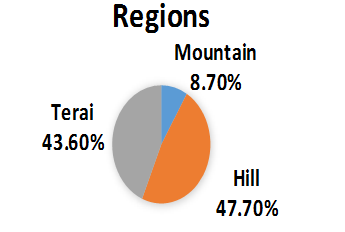

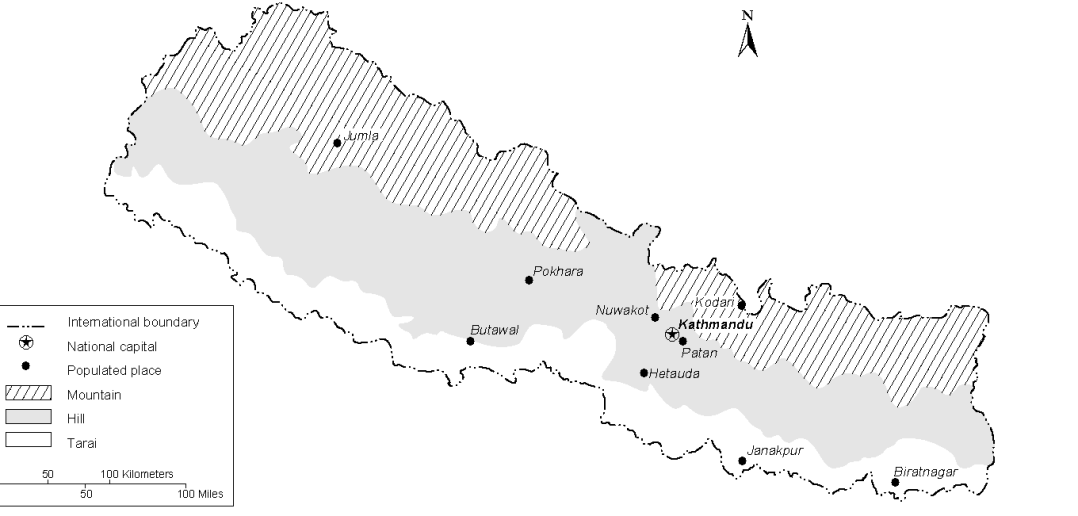

History and geography divide Nepal by caste, ethnicity, money, region and gender. The three geographic divisions, as in the map below, are the mountains, the hills and the Terai or Madhesh.[1] The Pahadis (hill dwellers) are richer and a majority. The people of the Terai are poorer. Kathmandu, the capital, and its surrounding valley are in the hills and have long dominated politics.

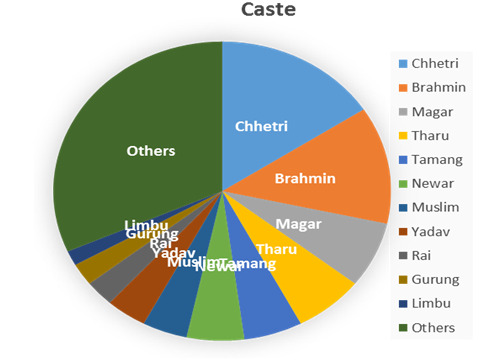

Nepal’s caste system dates back to 2000 BC, when Indo-Aryans moving from India brought the system with them. The caste system was legalized by Jayasthiti Malla, a 14th-century king, with the Brahmin (priests) and Chettri (warriors) at the top, the Terai keeping their Indian castes, and the Tibeto-Burmese divided among various strata. The ethnicities occupy distinct regions to some extent.[2]

All these divisions drive voting behavior, with all groups voting separately as blocs. That voting behavior falls on an ideological spectrum akin to that in the West, though in general all political parties are farther to the left. To the center-right is the NC (Nepal Congress). The NC attracts the old royalists, those who once supported the monarchy, and social and economic centrists and conservatives. The military has long allied with such groups. The left end is the moderate leftist CPN-ML and the more extreme Maoists. All parties are secular in ideology and influence and now renounce violence in theory and in practice. However the Maoists are the political offshoot of a rebel group that fought a civil war from 1996 to 2006, seeking to make Nepal a communist state. The military fought against them with support from the centrists—particularly the royalists. However at the end of the war allegiances shifted and the NC and CPN-ML made common cause in the name of democracy, ousted the king, signed a peace agreement and started work on a new constitution.

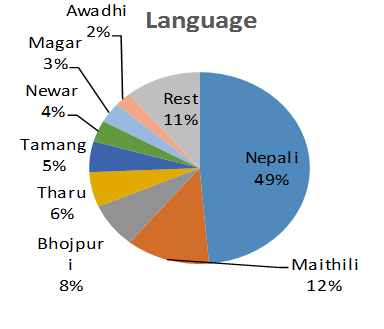

Though voting falls along social divides, Nepali democracy is still secure—a point of considerable strategic import to the West. In the current political climate, no group has the majority, as the charts below show. There is more than one dominant party, and power has stably switched hands before. Other destabilizing elements that bedevil young democracies are also absent or weak. One such element, civil war, is unlikely to repeat itself. Another, a strong monarchy, is gone for good now. Kings have effected coups in Nepal’s historic past, deposing elected leaders in 1961 and 2005; however, republics rarely revert to kingdoms, and the military is now considered apolitical. Communists, a potential antidemocratic force, are subject to the whims of the electorate, and suffer periodic electoral reversals that keep them from monopolizing power. Democracy is also strengthened by the influence of Nepal’s other neighbor, India. The NC traces its origins to the struggle for Indian independence in the 1940s when the founding leaders of the party allied with Indian nationalists.

Figure 3. Demographics of Nepali diversity.[3]

For democracy to function in a heterogeneous country, compromise helps. Here, too, Nepal has made considerable progress. The Maoist civil war – demanding social justice for the oppressed – was waged at a time when the king held most of the power. Maoists have since compromised, renouncing violence. The peace agreement that ended the civil war required them to lay down arms, with some of their fighters getting integrated into the national army. The party is now explicitly committed to democracy. The NC has also compromised, jettisoning hopes for a constitutional monarchy. The NC, long allied with royalists, had supported the institution of the monarchy even when it politically opposed the king himself. The Maoists and ethnicity-based parties want states based on ethnicities; the NC and CPN-ML fear this would sunder the nation-state. This disagreement is, however, likely temporary. More states implies more variation in wealth and a stronger need for federal taxation to redress the greater imbalances. Maoists, however, want a loose federation. The current draft with fewer states might well stick; the Maoist position wanting more states strengthens central power, a contradiction of aims.

So despite divisions, or perhaps because of them, Nepal looks set for democracy, secularism and political openness, a future likely to raise its strategic relevance to the West. Primarily, the developed countries of the West can help with investments and technology. Nepal has eight of the world’s ten tallest peaks, including Mount Everest; the Himalayas contribute to tourism revenue, and developing tourism requires investment. While the country is prone to natural disasters such as earthquakes, these tragedies have little long-term effect on social and political conditions.[4] This topography also creates potential for hydroelectric power generation, coveted by energy-hungry India and China. Hydroelectric power is reusable and generates no carbon emissions and the West, along with the rest of the world, has a clear stake in promoting it.

The US, specifically, is in the best position to help. It looms large in Nepal’s economy, and the US is Nepal’s second largest export market, after India.[5] It also provides development assistance under programs such as the Economic Supports Fund program, but the net annual assistance is just 45 million dollars and could be significantly expanded. The US, also, has the West’s main organic constitution. Britain, for instance, has none; the constitutions of other Western democracies such as Germany, Italy and France are practically post-World War II creations initiated under allied guidance. Spain’s constitution is post-Franco; Greece too has a recent constitution.

However, politically, missteps have dogged US-Nepal relations. America labeled the Maoists terrorists until 2006. While the Maoists acted brutally during the civil war, the insurgency was driven by the genuinely dispossessed and was not anti-American in nature.[6] While the culture and the context differ considerably from the Western, and American, experiences, the Nepali populace has shown a similar basic aspiration for a democratic, pluralist, secular society that guarantees broad equal rights to the most vulnerable. The tolerance for consensus building demonstrated by both political leaders and the populace testifies to that aspiration. The US is in a position to help with technical expertise on constitution writing, something Nepal desperately needs after it failed to draft a secular, republican constitution in 2008 due to state delineation issues. In June of this year, Nepal’s major parties reached a consensus on a host of legal issues causing gridlock, and are now ready to give a constitution another try. The West, and America in particular, can provide needed help, along with trade facilitation, capital commitments, and targeted aid for human development. These are investments likely to be repaid in the future with a friendly country in a strategic location between India and China.

[1] “Nepal: Country Profile,” Nepal and Bhutan: Country Studies, ed. Andrea Savada (Library of Congress, 1993), xxxiv.

[2] Nanda Shrestha, “Chapter 2. Nepal: The Society and Its Environment,” Nepal and Bhutan: Country Studies, ed. Andreas Savada (Library of Congress, 1993), 74.

[3] Caste demographics adapted from “Appendix: Table 1,” Federalism and State Restructuring in Nepal: The Challenge of the Constituent Assembly, (Kathmandu, Nepal: United Nations Development Program, 2007), http://www.ccd.org.np/publications/report.pdf (data from 2001); regional demographics from Nanda Shrestha, 66 (data from the 1981 census); language demographics adapted from Yogendra Yadava, “Linguistic Diversity in Nepal Perspectives on Language Policy,” Seminar on “Constitutionalism and Diversity in Nepal, Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University, August 22–24, 2007, http://www.uni-bielefeld.de/midea/pdf/Yogendra.pdf.

[4]“Nepal: Country Profile,” xxxvi; Nanda Shrestha, 57.

[5] Bruce Vaughn, CRS Report for Congress. Nepal: Background and US Relations (Congressional Research Service, 2005), 17.

[6] Bruce Vaughn, 9–10.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.