LOS ANGELES — President, and aspiring Sultan, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has single-handedly transformed Turkey into one of the most threatening global forces of the 21st century.

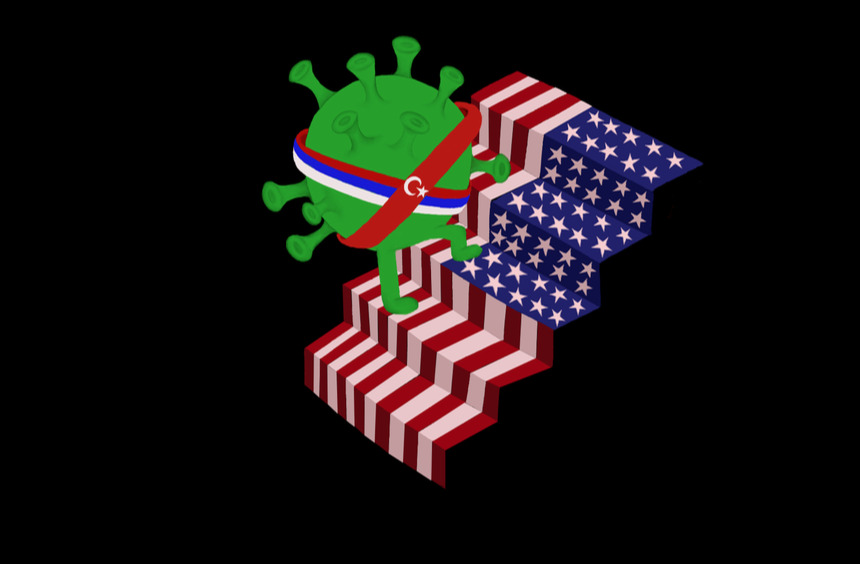

As the Western world was swept up in the chaos of the coronavirus pandemic and a historic U.S. election, Turkish President Erdoğan waged war against some of the most vulnerable regions in the world, rampaging the Eastern hemisphere with his violence and tyranny. With the power vacuum created by the West’s decreased involvement in foreign affairs in light of the pandemic, Turkey rose to the occasion, assuming an aggressive policy of interventionism with the aim of becoming a more significant player in global affairs.

Exploiting the global crisis which had Europe and the United States preoccupied, Erdoğan’s imperialistic expectations were realized through the use of force and terrorism, as intergovernmental organizations turned a blind eye to deal with domestic turmoil. Through its dangerously proactive foreign policy, Turkey has not only managed to intervene in, but also severely escalate, some of the most contentious and delicate political disputes in contemporary international relations.

Alarmingly for the West, however, Erdoğan has a new partner in crime: Russia’s very own Vladimir Putin.

The historical animosity between Russia and Turkey has been a longstanding security measure for the United States, an insurance policy of sorts. Since the Cold War, the U.S.-Turkey strategic alliance has revolved around a mutual opposition to Russian interests. However, the window of opportunity created by the pandemic’s sweeping devastation allowed for the birth of an unlikely partnership in the East — one that should give the United States and its allies ample cause for concern.

As 2020 ran its destructive course, Erdoğan and Putin struck while the iron was hot, making a play for the roles now vacated by a preoccupied West. Together, they wreaked havoc in Eurasia.

This complex yet strategic cooperation between Russia and Turkey can be traced back to the stalemate in Syria, where it first began to take root, according to Dr. Pavel Baev’s research with the French Institute of International Relations.

In 2016, following a dangerous bout of violence sparked by the destruction of a Russian Su-24M bomber, Putin managed to engage Erdoğan, along with then-Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, in the “Astana forma,” a new platform for negotiations between Syrian opposition forces. Despite outliving its efficacy by 2019, when President Trump made the sudden decision to withdraw U.S. troops from eastern Syria and instigated a new round of fighting, the Astana Process introduced a new model which replaced Vienna and Geneva as the main avenues for international mediation in Syria.

October 2019, however, saw a turning point in Russo-Turkish engagement in Syria. After the abrupt retreat of U.S. troops in the East, Turkish forces invaded 30 km of territory along the Syrian border, a ploy to strengthen the military presence and strike back at Kurdish units in the north under the guise of ensuring a “security zone.” In response, Putin undertook negotiations towards a compromise that would allow for shared control of this territory between Turkey and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Differing interpretations of the October agreement, however, sparked Turkish retaliation against the Syrian troop movement in the Idlib province, backing Moscow into a corner and forcing Putin to accept a ceasefire.

Erdoğan’s resolve proved to be an obstacle for Putin’s agenda, which encompassed “consolidating [Assad’s] dictatorial grasp on power.” Moscow and Ankara, then, were left at an impasse.

Paving the way for strategic cooperation, they realized that one issue existed which mutually served both interests. Wherever the United States and Western powers drew back, Russia and Turkey had an opportunity to emerge as major regional powers, solidifying their influence on the global stage.

In their joint offensive on the Eastern Hemisphere, Erdoğan and Putin set their sights on Libya next.

Exporting the Astana model to Libya, Russia and Turkey engaged in a series of internationally charged military confrontations from December 2019 to June 2020, resulting in a stalemate after the deployment of Russian fighter jets against the UN-backed Tripoli government.

Though their incentives differed, both presidents — dictators in everything but title — ultimately reaped the benefits of their passive cooperation, a delicate dance of manipulations and concessions, military offensives and backstage dealings, which put the two powers at center stage in yet another key region. While Erdoğan sought to “propel him[self]to the position of leadership in the Muslim world,” the fate of the Libyan dictator served as a grave reminder for Putin of the dangers of Western-backed color revolutions, not unlike those threatening to weaken his grasp on power in his own neighborhood, including the South Caucasus and Ukraine. Thus, Libya became a means to an end, facilitating Russo-Turkish rise to prominence in international relations while Libyans paid the price.

And in the most recent confrontation between Russia and Turkey, Nagorno Karabakh became the chessboard, and its civilians the pawns. In a transparent attempt to implement Pan-Turkic aspirations on the global stage, Erdoğan targeted the South Caucasus in the midst of a global pandemic.

Aiming to ascertain relevance in a geopolitically crucial region, Turkey deployed thousands of Syrian mercenaries to Nagorno-Karabakh, enforcing a military solution to the decades-long dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan’s attack seemed to be perfectly calculated, identifying a time frame when the fate of the South Caucasus would be of low priority in the greater world order — or perhaps more accurately characterized, disorder.

As international structures failed to take action, preoccupied with the pandemic and the fate of the American democracy, Ankara successfully cemented its position of influence over Baku.

From assistance in drone attacks to the deployment of F16 fighter jets, unwavering Turkish support — and therefore NATO resources — were a prominent characteristic of the Azerbaijani offensive in the 44-day war.

Meanwhile, Baev argues, “Moscow tried to stick to its traditional stance of a fair and forceful arbiter, but this ‘neutrality’ amounted to denying Armenia any support in the situation where Azerbaijan was receiving all necessary backing from Turkey.”

Putin’s passive stance in the conflict, coupled with a change in Turkish policy as it sought to encroach upon the Russian sphere of influence in the Caucasus, created the perfect grounds for an unlikely partnership. Russia could yield some influence in the region to Turkey if it meant solidifying Armenia’s long-term dependence on the Kremlin. Because faced with the threat of NATO member — and genocide denier — Turkey, Armenia would have no choice but to turn to Moscow, abandoning hopes for the West after the 2018 Velvet Revolution.

Applying the Astana model yet again, the two global powers realized that their best shot at cooperative co-dominance in the region was the absence of Western actors. While Turkey worked to ensure an Azerbaijani victory, Russia took care of eliminating other third parties. With the U.S. under the turbulent leadership of Donald Trump and France preoccupied with the pandemic, Moscow took the lead as the head mediator between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as fellow co-chairs of the Minsk group drew back to deal with the COVID19 crisis.

Today, Artsakh’s flag flies in Stepanakert and Shushi has fallen to Azerbaijan. Thousands of young soldiers are dead, the majority of the civilian population is displaced and over 200 prisoners of war are being illegally detained in Azerbaijan. Amidst all this loss and sacrifice, however, two parties seem to be left standing, unscathed and victorious.

Russia and Turkey emerge as the de facto victors of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Crumbling under the weight of an existential threat to the indigenous Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia has effectively ceded its status as guarantor of security to Russian peacekeepers. Putin has successfully forced his way into Nagorno-Karabakh, chipping away at yet another degree of Armenian independence — dangling the carrot that is security towards Yerevan in what some speculate was an orchestrated ploy. Russian interests in the Caucasus, as a result, remain intact. Meanwhile, Erdoğan formalizes Turkish influence in the region, furthering his pan-Turkic aspirations by ensuring victory for Azerbaijan.

What Turkey and Russia have accomplished in the 21st century should not have been possible. Global players had the power to put an end to their dangerous cooperation. Instead, organizations like the EU and the UN failed to act effectively, enabling Russo-Turkish partnership on critical issues.

The United States, in particular, has the most to lose from a Turkey-Russia alliance. As formal diplomacy between the two countries becomes more cooperative, the U.S. is forced to take action to keep its allies in check. Standing to lose its partnership with a strategic NATO ally in the East, the United States is justified in its increasing concern regarding the new foreign affairs direction of Ankara. The Biden Administration needs to take definitive action to counter the effects of lax Trump-era policy towards Russia and Turkey; otherwise, Putin and Erdoğan will go unchecked, propelling each other to prominence on the global stage with NATO resources, backstage dealings and an adversarial front.

International structures are in dire need of reform if they are to address this increasingly dangerous partnership, so as not to be incapacitated by every global crisis, vulnerable to exploitation when they are needed most. Foreign relations must divorce themselves from private interests with strict policies enforced to limit the influence of corporate greed on foreign policy. Where oil and arms deals corrupt diplomacy, viable humanitarian policymaking must be adopted in their place, necessary reforms extending into the grey area of informal international agreements as well. First-world countries who carry greater global responsibility must take a more active role in international law enforcement, fighting for human rights where other governments fail.

Moreover, the role of the West as an effective check on Russo-Turkish power cannot be emphasized enough. There is a consistent pattern of cooperation between Putin and Erdoğan flourishing in the absence of Western actors, realizing that shared influence in the East is favorable to being in a constant struggle for it.

The solution? Western players need to start showing up. Because when the United States and Europe are present at a negotiating table, democracy gets a seat, too.

Left to their own devices, Putin and Erdoğan jeopardize the fate of the entire Eastern Hemisphere.