This article is the third and final part of Glimpse’s series on Iraq

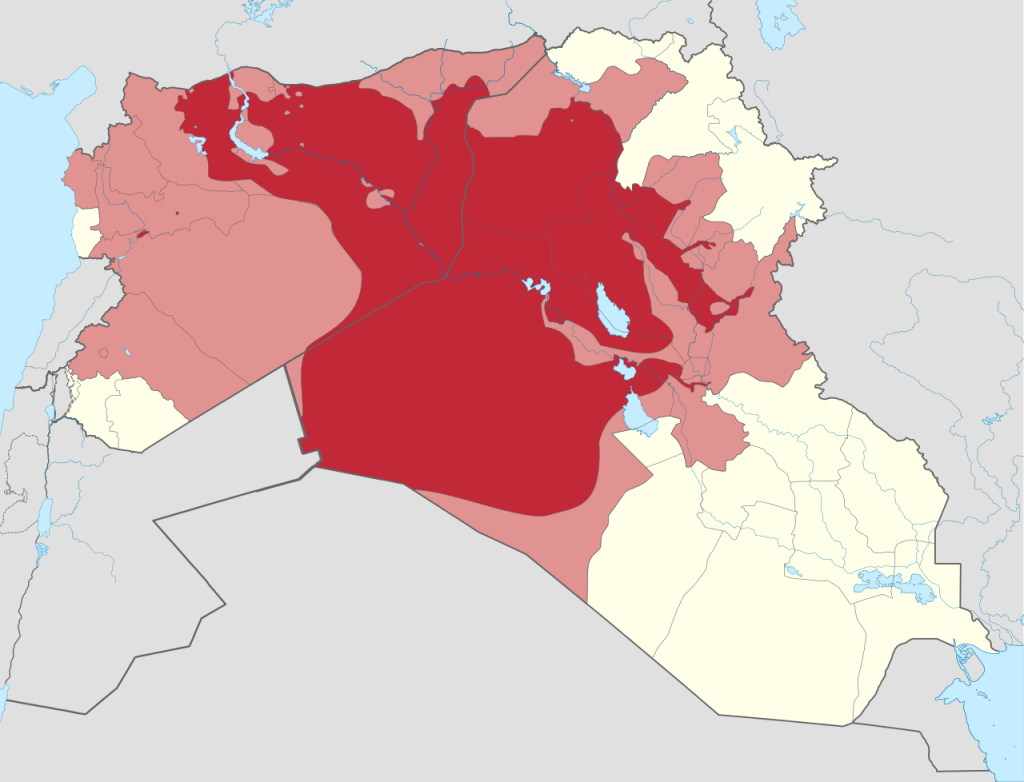

Recent weeks and months have seen the great Iraqi cities of Tikrit, Fallujah and Mosul fall to the former al-Qaeda regional group known variously as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, the Iraqi State of Iraq and al-Sham, or most commonly in Western parlance, ‘ISIS.’ The Fall of Fallujah a few months ago sent the initial shockwaves, and ISIS’s new conquest merely affirms their effectiveness as an organization.

Moreover, ISIS is not operating the way most jihadist groups have functioned in the past decade. Whereas most groups have focused on attacks and recruitment, as the al-Qaeda Core and its various satellites have done, ISIS has gone a step further towards fulfilling al-Qaeda’s original grand strategy: true to the “Islamic State” component of its name, ISIS has gone about holding territory, maintaining order, establishing institutions and providing services and its own form of justice to those under its domain. In this way it more closely resembles the pre-2001 Taliban, who for all their failings were at least able to maintain a reasonably orderly state in Afghanistan—a feat no one has since managed to replicate. Though some commentators doubt the longevity of ISIS’s state, it cannot be denied that ISIS is a successful contender on the international stage with a different and more sustainable sort of power the al-Qaeda core has never been able to achieve.

This invariably presents problems for US policymakers. A major part of the narrative promulgated during the War on Terror has been the barbarism and cowardly terror tactics used by Islamist groups. How, then, do we explain that our Islamist foes are now maintaining order in Iraq better than we ever have, to the point of actually setting up a Consumer Protection Agency where the kings of Babylon once rode?

Moreover, American (and, in general, Western) policy has relied on the Westphalian international system for determining what is and is not a state, and thus which organizations and entities we can legally have relations with. For the most part this has been a relatively clear-cut distinction; after all, Western influence has been so profound in the last few centuries that today, virtually every internationally recognized state in the world traces its intellectual origins to Western thinkers.

But what about those cases along the periphery of the traditional civilized world that do not exist as a state as we know the term, but nonetheless emerge as the primary political grouping by which individuals identify?

ISIS is not Iraq’s only quasi-state. In the north of Iraq, as well as in parts of Turkey and Syria, the Kurds have for many years existed on their own, providing their own security and basic services, yet remaining unrecognized by the international community. They have been essentially autonomous since before the Saddam regime, and since the Fall of Baghdad in 2003, they have governed the most stable area of Iraq—stable largely due to their superior, organic political culture.

In Yemen, the government in Sana’a holds only official sovereignty over the Arabian Peninsula’s tip. Houthi tribesmen, Shi’as with supreme antipathy to the central government, rule the hills and mountains. It is against these insurgents – as well as the al-Qaeda operatives in their midst – whom the infamous US drone strikes have targeted over the last few years.

Somalia has existed under a sort of warlord-like system for many years, and while it is decaying and collapsing at the moment, it has nonetheless managed to produce some of the main non-state power brokers in the Horn of Africa.

Meanwhile, one need only look to Nigeria, Congo, Libya, Afghanistan and the Caucasus to see traditionally structured and ethnically based political entities waging insurgencies against other ethnic groups and the local governments. It is not hard to imagine that, were these groups slightly more successful, they would easily be compelled to institute such civilizing policies as those ISIS is putting in place in Iraq. Moreover, though these semi-states would assuredly be diplomatically and technically less advanced than most other states, they would invariably enjoy a much higher degree of legitimacy than most developing world states that are effectively Western institutions trying to fit non-Western societies. The recent history of insurgency suggests that this is a dangerous situation: groups with dramatically inferior technology and tactics can outlast the onslaughts of Western militaries due largely to the passionate support of local peoples.

It is time the United States cease the internationalist formality that has hitherto constrained it from operating effectively in the Virgilian quest to spread political order to the ends of the Earth. What matters is not a commitment to Western styles of democracy, nor an agreed-upon definition of the rights of the individual, but the basic good of political order, in whatever form and justified by whatever ideology or culture. ‘Power Pluralism’ can be the America’s most effective tool in halting the advance of anarchy and promoting a world where powers can speak to each other in a common forum—something that the United Nations has succeeded at only partially, and manifestly failed at in regions of the world not sharing the West’s advanced degree of social and political development.

Two political thinkers, Francis Fukuyama and James Kurth – both students of the famous and infamous 20th century political scientist Samuel P. Huntingon – offer slightly differing but fundamentally similar visions of political development. In his magisterial treatise ‘The Origins of Political Order,’ Fukuyama cites a “centralized source of authority,” “the rule of law” and “accountable government”[1] as the three pillars of political order, which reinforce and complement each other, but tend to exist in differing degrees in different societies. Fukuyama places a premium on democratic accountability, accountability to the people through representative institutions. Thus, echoing his ‘End of History’ thesis, Fukuyama argues that Western democratic forms of political order are fundamentally more representative and stabilizing than traditional religious and cultural forms. Nonetheless, a primacy is still placed on Weber’s monopoly of legitimate force – the state – as the source of order.

James Kurth, in his article “Coming to Order,” details a similar hierarchy of political goods, using the Declaration of Independence as his model. Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness – in the respective forms of Order, Law, and Civilization – are the chief fruits of the state, and generally they correspond to Fukuyama’s state apparatus, rule of law, and democratic accountability. Kurth, however, remains loyal to his mentor’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’ thesis, and emphasizes a relative equality of forms of accountability and social cohesion. The religious bonds linking Sunni societies and separating them from Shia societies are, in Kurth’s account, as strong as or stronger than the interested democratic ties linking Westphalian, Weberian, Western states.

Nuances aside, Fukuyama and Kurth are probably both right in their own respective ways. The nearly universal adaptability of Western democratic legitimacy to nation-states with cultures as diverse as those of Argentina, Japan and Israel suggests that most societies, upon reaching a certain level of social, economic and political development, wind up utilizing some form of democratic accountability to manage the interests of their populace. But the enduring popularity of traditional forms of legitimacy, particularly in the Middle East and Africa but even traceable in the Confucian-based cultures of East Asia and the patriarchal authoritarianism of the Slavic states, means that different versions of accountability cannot be discounted. And as no nation-state, however powerful, can force other nations through the equivalent of centuries of political development and expect to succeed, it is important to heed both Fukuyama and Kurth, and preserve democratically accountable governments where possible, but deal with governments accountable by other cultural means as they exist while encouraging their further development and integration into the global maritime system. This is the essence of Power Pluralism.

But Power Pluralism goes a step further. It is one thing to support existing states; it is quite another to watch the rise and fall of other states, and pledge support to the actors most capable of protecting local order-one of whom, it seems, is ISIS. This is clearly a morally dubious task, as oftentimes those actors most capable of protecting order or holding legitimacy on the domestic scene are the very actors most opposed to our nation’s values and interests on the international stage. At times it may be wisest to use the old Chinese strategy of keeping the ethnically homogenous “barbarians” divided against each other so “they” cannot unite against “us.” But, in the modern world, where political development is imperative to Mankind’s future, and non-state groups flourish where disorder reigns, such a strategy would be “barbaric” in itself, regardless of its usefulness. More promising would be the lesson which that European powers learned in the American Civil War, and which America learned in the Russian Civil War and the Vietnamese War.

It is well known that, much to Lincoln’s chagrin, the governments of Britain and France gave covert support to the Confederacy during the War Between the States. This was perfectly natural, as it was in their interest to see a divided North American continent, and had they succeeded their power position in the North Atlantic might have been maintained. Unfortunately for them, however, the Confederacy was never going to win the war, in the long run. It might have achieved a decisive victory and maintained independence for a few years, but its industrial weakness and geopolitical vulnerability would eventually have placed it back in the arms of the Union. The North was destined to win the great game over the long term, and North America – though it would have had a bloodier heritage – eventually would have been again united under Washington, DC. The fact that Britain and France gave their support to the loser estranged the Franco-American and Anglo-American relationships for decades to come, and may have contributed to the Americans’ dragging their feet in the First World War. A Washington-London-Paris entente, conversely, might have contributed to stronger transatlantic order earlier in the 19th century.

When the Russian state collapsed in 1917 and the Bolsheviks rose up against Romanov forces, England and the United States saw a dangerous red tide rising with Lenin’s revolutionary movement. To counteract this, they provided military aid to the “White Russian” forces of the Czar, and strove to put down the Bolshevik Revolution. Ultimately they failed, and the Soviet Union began its life in fundamental opposition to the West with a fury greater than Czarist Russia had ever had. Now, this was ideologically an inevitability. But, it would be interesting to consider whether the West and the Soviet Union would have had better relations had the humiliating nail of condemnation not been driven through the coffin of West-USSR relations in the first half of the Twentieth 20th century. It seems that EH Carr, in advising the British to ally with the rising Bolshevik forces because their victory was inevitable, was morally wrong, but politically prescient.

And in the Vietnamese War, the United States propped up an illegitimate and inefficient regime in Saigon against a homegrown nationalist guerilla force that enjoyed the full support of a majority of the Vietnamese population. Washington might have spared itself tens of thousands of lives and wave after wave of devastating cultural revolutions at home had it worked, earlier on, to reach an understanding with the North Vietnamese.

Of course, allies can and often do turn on each other, with ugly results- witness the aftermath of the Second World War, or the US-backed Mujahedeens’ transformation into the Taliban during the 1990s. But conventional wars are far easier to fight than counterinsurgencies, and in the 21st century the forces capable of providing order have all been insurgents. It may well be better to win a counterinsurgency by propping up an unsavory regime that we’ll have conventional relations with later, than to allow an insurgency to rule and accomplish nothing with diplomacy.

Where do we go from here? It would probably be prudent to reassess what, exactly, American interests are. But, if an orderly world where the forces of chaos are held at bay and states cooperate and compete in a civilized and organized fashion is the world we want, then it would be logical to start working with whoever, in every region, is most capable of providing order. These relationships do not have to be amicable—this is the kind of relationship we have with authoritarian states, taken even to the next level. But these kinds of dealing are infinitely preferable to isolating the guardians of order, which can only result in such entities’ ideological radicalization and political stagnation.

In this context, the Obama Administration’s opening up to Iran is a step in the right direction. Here we have the United States working with a vehemently anti-American, ideological and human-rights-oppressing regime on the issue of nuclear nonproliferation. But it’s a regime that can keep order over a huge area, while providing one of the highest standards of living in the Muslim world. It’s not pretty, it’s morally troubling and it’s less exciting than strategic competition and war. But, it opens the table of negotiation between the power brokers in one polity, and the power brokers in another. That’s the way things get done. Conversely, the continued recognition of Nouri al-Maliki’s weak and corrupt government in Iraq is detrimental to American interests in Mesopotamia and the cause of order in general. Were the United States to begin working, formally or informally, with ISIS and the Kurds, there is a much greater prospect of regional stability, rather than the current state of chaos enabled by our ignoring the Kurds and condemning (but not really fighting) the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham.

Recognizing ISIS for pragmatism’s sake would bring more than just moral queasiness. The group has effectively replaced the al-Qaeda core as the leader of the global jihadist movement. We must be wary that they may maintain plans to strike at Israel, Europe, American military bases, or even the American homeland, all the while dealing with our allies and us duplicitously. A Taliban in Mesopotamia would be an irony and a tragedy.

But, it is a risk worth taking, if for no other reason than the fact that the United States is effectively powerless to do anything about ISIS’s regional standing. In fact, a 2007 article by Jakub Grygiel suggests that a group like ISIS possessing a state may weaken the movement and make them more amenable to American demands. Historically, when “barbarians” have settled down and started the hard work of governing and diplomacy, they have proved inept and become dependent on the international systems led by their former targets. Perhaps the world’s first caliphate since the fall of the Ottoman Empire will, embarrassingly, find itself begging for an accommodation with the West it hates.

Clearly, prudence is the most important thing to keep in mind here. We shouldn’t go around treating every rebel movement the way we treat Great Britain, nor should we sacrifice our relationships with key allies simply due to temporary convenience. But we should weigh what, in the end, is the best interest of the American polity, and the best interest of the peoples of any particular region whom we so profess to care for. I sense that, if ISIS succeeds in keeping order, then it will provide a compelling argument for a fundamental readjustment of American views of sovereignty and the state. Perhaps Power Pluralism will begin to look attractive to those in power in the coming years, as the world gets crazier and we realize how ineffective and weak we Americans are without regional partners. This is the beginning of what George Kennan, “the father of containment,” would call wisdom.

[1] Fukuyama, Francis: “The Origins of Political Order,” pg. 13-14The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.