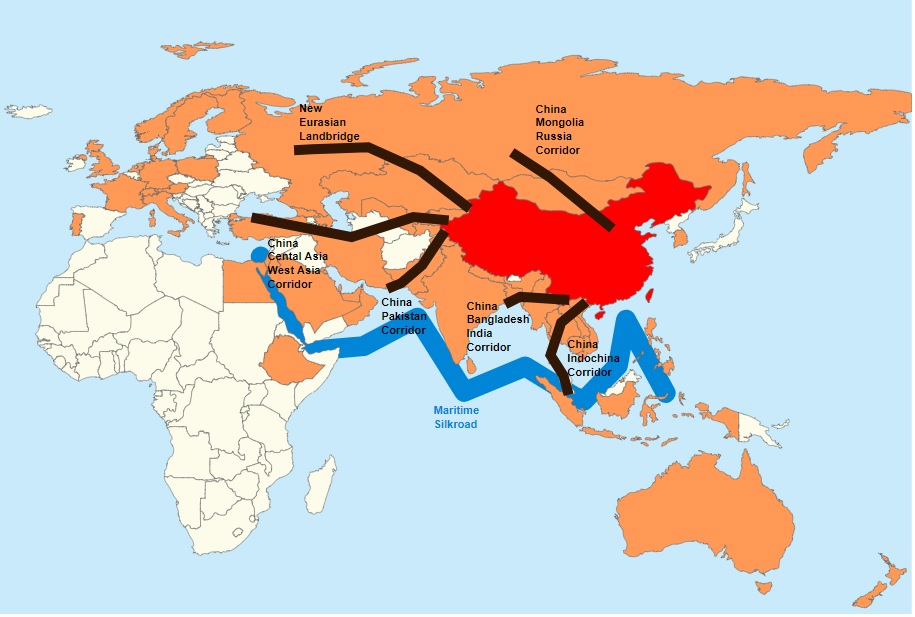

On March 28, 2015, Beijing introduced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a Chinese-led venture that aims to connect parts of the Asian, European, and African continents with each other through infrastructure projects. Using a two-fold approach: the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ on land and the ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ over water, China hopes to expand its markets and its economic reach in the region. However, although the BRI has been presented as a positive change for the world, many countries, especially those within the EU and US, are concerned about the implications of the initiative. For instance, recently India, with US support, denounced the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, as it passes through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. This move has reignited debates over control of the various projects and China’s overall ambitions.

Why the BRI?

Over the past few decades, China’s economy has grown rapidly, allowing it to shed its status of a dependent third-world country to become one of the leading players in the international economy. Driven by the Chinese government’s emphasis on the growth of business, the country’s GDP has grown an average of almost 10 percent a year, the largest sustained expansion of any economic power. Today, China is the world’s third largest economy, trailing only the European Union and United States.

However, since 2012, the economy’s growth has slowed, with the GDP only increasing by a little under seven percent in 2016, the lowest rate in a quarter of a century. In October 2016, Japan surpassed China as the largest holder of US debt, further evidence of China’s slowing growth. This slowdown is caused by systemic rather than cyclical issues, a problem many developing economies encounter after a period of rapid growth. As the Chinese labor force relocates from rural to urban areas and the country edges toward the cutting edge of technological development, its capacity for growth shrinks considerably.

Beyond this, the Chinese government has overinvested in stimulus spending, creating high interest rates that will prove unsustainable. These high interest rates in turn contribute to a growing debt crisis: Chinese debt has increased almost four times over in the past seven years, from $6.9 trillion to $26.6 trillion. This overinvestment has touched the international community as well: foreign direct investment from China tripled in the past five years, inundating global markets with Chinese funds. All of these factors have led the Chinese to seek new markets for their goods, leading to the birth of the BRI.

Friends with Benefits: Opportunities for China and its Partners

The BRI offers significant benefits to both the countries in which projects are implemented and for third parties. Countries with projects implemented within their borders stand to gain from increased direct access to markets and facilitation of trade. Hence, local governments such as Duisburg and Hamburg in Germany, Madrid in Spain, and Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the Netherlands have the opportunity to benefit by serving as “China’s gateway to Europe and as a regional hub of the Belt and Road” because of their strategic geographic location and their current strong economic ties in the region. In the same way, third parties, including businesses that engage in export trading and construction, gain from directly receiving the return on investment from these projects in the future.

For foreign countries, including the US and European nations, there are even more potential benefits. Through partnerships and flagship initiatives, countries can reach economic goals and boost economic health. For instance, the EU linked its Investment Plan for Europe, known as the Juncker Plan, with the Belt and Road Initiative. This partnership allows the EU and China to work in tandem on infrastructural projects that complement the objectives of both parties.

One potential political benefit for foreign countries participating in BRI projects is the potential to shape Chinese initiatives to be more favorable or compliant with their wishes. For example, European countries could identify projects that enhance land connections between Europe and Asia, but bypass Russia. This would allow them to not only develop economically, but it would also help alleviate the security concern of Russia controlling vital trade routes and thereby decrease European reliance on Russia.

Foreign involvement in the BRI can also increase those countries’ clout within China to guarantee that it does not expand without oversight. According to Daniel Guyader, the head of the Division in charge of Global Issues within the Department of Multilateral and Global Issues at the European External Action Service (EEAS), involvement can be seen as a way to “influence from within” to check growing Chinese influence in Europe and in the world’s economy. This is one way to soothe international fears of Chinese domination in international markets and may prove to be an essential part of the future of international commerce.

Not All that Glitters is Gold: Challenges and Potential Roadblocks

However, the BRI also presents a host of challenges to foreign countries. For one thing, foreign companies still do not have nearly the same level access to Chinese markets that China has to foreign markets. For example, China and the EU do not have a bilateral investment treaty, so most of the current BRI investment projects are mainly funded by Chinese state-owned banks or regional banks, rather than multilateral banks, like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) or the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or international investors. Regardless of whether this is due to China’s enduring protectionist stance or its overcapacity in production, third parties like the US and EU may stand little to gain from BRI investment projects, while China will majorly benefit from each project. In terms of absolute gains, both parties win, but in terms of relative gains, China benefits much more.

Additionally, as third party countries eagerly compete for access to Chinese markets and investment in certain projects, China may exploit this competition and make deals only with countries that will give China relative freedom on projects and percentages on return. The ultimate concern of this ‘checkbook diplomacy’ is that it will pit countries against each other and lead to a slippery slope of compromising with China more and more until all or the majority of deals made will almost solely benefit China.

A Double-edged Blessing or an Ambiguous Curse?

Still in its initial stages, the BRI has potential to be either an economic boon that increases international collaboration or a destructive force that exacerbates existing tensions. Given the current turmoil in Europe, the effects of the BRI in Europe are of particular note. On one hand, it has created business opportunities through investment and improved infrastructure, presented a means to further the EU economic agenda and provided a channel to influence Chinese policy decisions. On the other, BRI projects seem unfairly beneficial to China, may threaten EU cohesion and violate EU business standards. Already, the EU has positioned itself as less than friendly toward large, international companies. Considering the latest tax fines against Apple and Amazon, it seems almost impossible that Europe will embrace China’s massive venture. However, as the Chinese seem determined to continue with the initiative, the future nature of Sino-European relations will be determined by how the EU responds to its current situation and we will have to wait and see what the outcome will be.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.