Last week, the Air Force announced that SpaceX would be allowed to compete against United Launch Alliance (ULA) for lucrative Department of Defense (DOD) space-launch contracts. The announcement, which came after years of controversial certification proceedings, represents a major victory for SpaceX as the company seeks to expand its presence in the defense and commercial launch industries.

SpaceX’s certification means that it will now be able to launch under the Air Force’s Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program. Established in 1995 as a way to ensure the availability of launch vehicles for national security sensitive programs such as GPS and missile defense satellites, EELV was intended to lower launch costs and increase reliability by pitting Boeing and Lockheed martin in a competition for contracts.

But the Air Force’s plans to lower prices through competition evaporated in 2006 when Boeing and Lockheed Martin formed ULA as a joint venture and united the two companies’ launch divisions. Since then, costs have steadily risen as ULA, through its expendable Delta and Atlas rocket families, maintained a status as the US’s sole provider of national security related launch vehicles.

Until last week, that status was criticized by many, including representatives at SpaceX, as a virtual monopoly. To make matters worse, since 2003 the DOD has granted ULA and its predecessors billion dollar “launch readiness” (ELC) payments and in 2012 the Air Force agreed to purchase 36 rocket cores – enough for 28 launches – from ULA over a period of five years. SpaceX has contested both actions as anticompetitive.

In the face of rising costs, the Air Force announced in 2012 that it would open up the EELV program to additional launch providers that could complete an outlined certification process. That certification, which SpaceX acquired last week, was marred in controversy as SpaceX complained about bureaucratic sluggishness and an alleged cronyistic relationship between the Air Force and ULA. Last spring, SpaceX’s grievances culminated in a lawsuit that was settled in January with an Air Force agreement to expedite the certification process to the summer of 2015.

Now that that certification process is complete, several factors will impact ULA and the launch industry’s future. Though ULA is guaranteed future launches as per the 2012 block buy deal, it will need to compete with at least 9 other launches until 2018 and every launch thereafter. Appealing to a cash-strapped pentagon, SpaceX can beat ULA on pricing, offering launches for under $100 million, dwarfing ULA’s $160-350 million.

Meanwhile, ULA’s dependence on the Russian-made RD-180 engine for its Atlas V adds an additional obstacle. In December of 2014, congress banned the use of RD-180s for national security related launches. Though the edict exempted past contracts, ULA doesn’t think it will have enough to sustain it before the company rolls out its Atlas V replacement vehicle sometime around 2023. Making the situation more pressing, ULA announced plans to retire all but the heavy variants of its Delta family by 2019. ULA doesn’t believe the Delta IV, which costs on average 30% more per launch that the Atlas V, will be able to compete with SpaceX’s Falcon 9 for future EELV contracts.

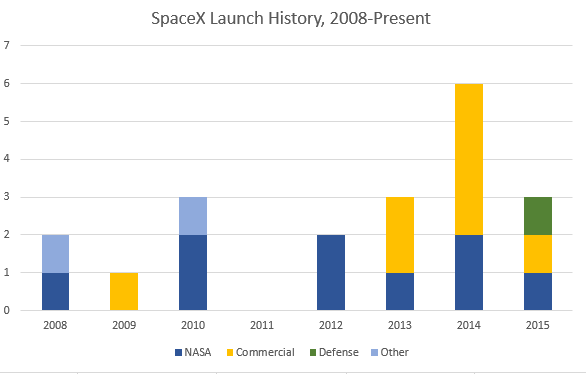

As SpaceX encroaches on historically ULA territory, the Air Force has already announced intentions to phase out its ELC payments. This, coupled with the factors noted above, makes the time from now until the early 2020s, when ULA can finalize its Vulcan launch system, critical to ULA’s survival. Presently, the Air Force’s EELV launches make up the bulk of ULA’s business, making it imperative for the company to continue winning Air Force contracts or to expand into the commercial launch industry. This is not the case for SpaceX, which even in its infancy has a diverse manifest of commercial launches and NASA resupply missions to the ISS.

But the groups most shaken by SpaceX’s sudden rise may not even be ULA. Actors in the international commercial launch arena, particularly the EU-based Arianespace and the US-Russian International Launch Services (ILS), have already began to take preemptive measures against SpaceX’s rapid expansion.

Arianespace, historically owned by a consortium of European government agencies and companies, was founded in 1980 as the world’s first commercial launch provider. With a claimed 60% market share in 2014, Arianespace dominates the commercial market with its Ariane 5, Vega and Soyuz vehicles. Until recently, its main competition has been the US-Russian ILS, which fights for dozens of launch contracts each year with its Proton launch family.

Like ULA, Arianespace and ILS are threatened by SpaceX’s ability to undercut them on price. For ILS, recent launch failures have compounded that threat by eroding confidence from commercial satellite companies and restricting Proton launches to the patronage of Russian customers. Its difficulties have led to its dismissal by many commentators who increasingly treat SpaceX and Arianespace as the only relevant competitors on the market.

Between SpaceX and Arianespace, Ariane’s edge comes from its ability to launch heavy payloads SpaceX’s Falcon 9 cannot and its reputation as a nearly impeccable launch provider over the past three decades. However, Arianespace can only cling to these advantages for so long as SpaceX nears completion of its Falcon Heavy and grows its own manifest of successful launches. As of now, both the Ariane 5 and Falcon 9 are fully booked through 2017.

But what price advantage SpaceX currently has could be dwarfed by what it may have. Since at least 2011, SpaceX has been attempting to develop a reusable launch vehicle, an innovation Elon Musk says could lower launch costs by “as much as a factor of a hundred.” Though engineers at organizations such as NASA and the French space agency CNES are skeptical, if SpaceX successfully pioneers reusability it could eradicate its competition.

Arianespace has responded to SpaceX’s assaults by lowering prices for smaller satellite launches to around $90 million (still shy of SpaceX’s $60 million) while adding price hikes for its low-competition heavy payload contracts. Additionally, on June 5 the company revealed that it is now attempting to match SpaceX on the reusability issue through a new project known as Adeline: a drone that can transport a rocket’s first stage engine and electronics systems back to Earth. Though it’s unclear when either launch provider will make their respective reusable vehicles ready, Arianespace has a set a target date between 2025 and 2030.

The privately held SpaceX has also challenged Arianespace’s public and somewhat decentralized structure. Last year, a joint venture between Airbus and Safran known as Airbus Safran Launchers began to consolidate private control over the company. Now, in an attempt to reduce costs and increase efficiency, the French government is planning to sell its remaining 35% stake in Arianespace to Airbus Safran Launchers, giving the infant venture a nearly three-quarters share of the world-established launch provider.

But amid privatization efforts, Arianespace has enjoyed subsidies of more than €100 million ($112 million) from the European Space Agency (ESA) and, for a company that sells in USD, a sharp fall in the value of the euro against the dollar from 2014 to early 2015. Despite the advantages, the ESA agreed in late 2014 to provide €8.2 billion ($9.2 billion) over the next ten years the assist in the development of Arianespace’s next generation launcher.

Arianespace’s relationship with the ESA and European governments will undoubtedly draw fire from SpaceX which has already fought bitterly with ULA over what it deemed as unfair treatment. But its assistance is unlikely to end anytime soon; for Europe and the ESA, Arianespace assures European access to space, access that the EU is unwilling to let die at the hands of an American space startup.

The responses from Arianespace and the Air Force show that in just several years, SpaceX has managed to upset the status of government-sponsored legacy launch providers on both sides of the Atlantic. As it continues to benefit handsomely from NASA resupply missions to the ISS and prepares to rake in additional funds from the EELV program, the rivalries it’s forming – and the potential tensions between competing nations – will likely only intensify.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.