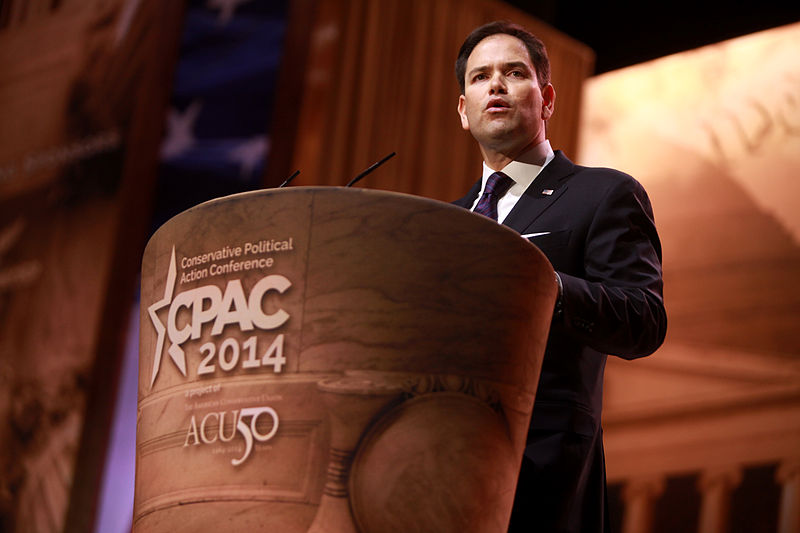

President Obama’s announcement to normalize diplomatic relations with Cuba elicited a plethora of political commentary, particularly from the right and prospective presidential candidates. Though many lauded the president for his leadership in addressing a policy that has, for over 50 years, failed, politicians including Marco Rubio, John Boehner, Jeb Bush and Ted Cruz wasted no time condemning the White House. Senator Marco Rubio, a Cuban-American himself, however, led the charge. While his protestations and impassioned avowal to thwart the president’s initiative seem legitimate, both a political and Orwellian-style literary critique will expose the hypocrisy of his commentary. He obfuscated a complex relationship, culture and regime with sensationalistic rhetoric. And, though certainly not insincere, his claims are entrenched in an outdated Cold War-era disposition that neither align with US nor Cuban interests. His public outrage also happens to conflict with many other aspects of the Senator’s foreign policy.

Following the president’s announcement, Marco Rubio immediately held a press conference and made numerous television appearances in which he vehemently condemned Obama’s foreign policy as one that’s “not just naive, but willfully ignorant of the way the world truly works.” As the son of Cuban immigrants, his perspective on US-Cuba foreign policy seems more an outdated expression of filial obligation than a testament to his politics. As he details his book, American Son, his grandfather, a fervent Castro adversary, became his political inspiration, indoctrinating him with his generation’s Cold War ideology. Growing up among Cuban exiles only solidified this enmity towards the Castro regime. However, with the majority of Cubans under 65 opposing the embargo, his commitment to politics of the past have isolated him from popular opinion. As he caters to a very small population of older, conservative Cubans in South Florida, he alienates not only the younger Cuban generation, but also the majority of Americans who support lifting the embargo. His outrage is therefore a “Washington anomaly”— an emotional rather than reelection-driven political response.

Despite being the Cuba expert in Washington, his family background might have completely disconnected him from pulse of the Cuban people. According to the Senator, the deal between the US and Cuba was predicated upon the “false notion that engagement alone automatically leads to freedom.” However, the White House has repeatedly emphasized that cultivating a relationship with Cuba will enable the US to “renew our leadership in the Americas, end our outdated approach on Cuba, and promote more effective change that supports the Cuban people and our national security interests.” There is no sudden call for a “Cuban Spring,” but rather small, incremental change that comes with greater exposure. President Obama isn’t deluded to believe he’ll single-handedly bring democracy to Cuba, or that the 80 year-old Castro brothers might suddenly eschew communism and come running into the arms of the US to feel the warm embrace of a constitutional republic.

Rubio’s secondary objections are less valid, less ideological arguments than hypocritical inflammatory rhetoric. These changes to US foreign policy to Cuba, he claimed, “will tighten this regime’s grip on power for decades to come and significantly set back the hopes for freedom and democracy for the Cuban people.” That doesn’t sound good. But, one: is that really true? And, two: does this align with Rubio’s foreign policy towards countries with equally questionable human rights violations?

First, Americans should question the validity of his statement. “Decades” is already an exaggeration—the Castro brothers will not celebrate their 103rd birthday with a tight grip on power. Moreover, the US has sustained their reign through isolation. The Castros have deflected from their own ineptitude by blaming Cuba’s financial woes on the US embargo. Although it won’t dissolve completely until Congress decides to legislate, Fidel and Raul Castro’s infamous excuses will inevitably receive more criticism as the US assumes a larger role on the peninsula. Rubio’s accusations are not only less accurate than Americans might assume from a “Cuba expert,” but they also don’t align with many of his other ideas.

As the White House pointed out, Rubio supported the nomination of Senator Max Baucus as the US ambassador to Beijing in order to for Americans to better espouse ideas of democracy and freedom in China. At the confirmation hearing he stated, “I think you’ll find broad consensus on this committee and I hope in the administration, that our embassy should be viewed as an ally of those within Chinese society that are looking to express their fundamental rights to speak out and to worship freely.” He endorsed engaging a state equally criticized for its flagrant human rights violations in a dialogue that he won’t even entertain with Cuba. Moral righteousness is of utmost importance—unless of course we’re talking about an economic super power. Rubio admitted this fact in a recent interview with CBS, when he insisted engagement alone doesn’t lead to freedom, citing the Chinese who are “no more politically free today than they were when that engagement started.” However, when asked if he himself would eradicate ties with China, he claimed “comparing China to Cuba is not a comparable analogy because China is the second largest economy in the world, they have the third largest nuclear arsenal on the planet, and they are the most populous state on the planet.” National interests often hinder the US’s ability to advocate for human rights reform. Given the current landscape of affairs, Americans appear to place far greater value on economic opportunity than the plight of human suffering or oppressive institutions and states, a trend for which Rubio is no exception.

The question also remains: how should the US orchestrate serious political change and human rights reforms without fostering some form of a relationship? The previous policy hasn’t dismantled its dictatorship or improved the conditions for the average Cuban. To expect change with the same policies that have failed for 50 years is not only naive but also obstinate.

Throughout his press conference, Rubio belabored the “brutal dictatorship” point as if it substantiated all his objections. However, it doesn’t quite align with his past statements either. When Americans debate the brutalization of human beings in the hemisphere must they not at least acknowledge Guantanamo—the epicenter of inhumanity? Despite the fact that Rubio condemns Cuba for its human rights abuses, he also demanded Ahmen Abu Khattala, captured suspect for the Benghazi attach, be interrogated and detained in Guantanamo back in June. Then, when Americans learned of the US’s own abuses in the Senate’s report on the CIA torture program, Rubio decided to disregard the US’s own offenses once more. He responded to reports of rectal rehydration and water boarding by tweeting, “Those who served us in [the]aftermath of 9/11 deserve our thanks not one sided partisan Senate report that now places American lives in danger.”

Rubio also expressed concern that normalizing relations with Cuba would not only embolden brutal dictators, but also send a message of US weakness to the international community, saying, “appeasing the Castro brothers will only cause other tyrants from Caracas to Tehran to Pyongyang to see that they can take advantage of President Obama’s naiveté during his final two years in office.” Firstly, the US is one of the last remaining countries to recognize Cuba. In fact, for the 23rd time in history, the majority of the UN General Assembly voted to end the US embargo against Cuba (Yea: 188 member states, Nay: the US and Israel). If Obama’s sending a signal of naiveté, then at least he is in good company. Secondly, the word “appeasement” sends a terrible chill down the spines of all those who have studied World War II, yet, behind the sensationalistic rhetoric lies the implication that diplomatic relations with tyrants denotes appeasement and invites countries to exploit the US’s willingness to work with non-democratic regimes. I suppose that means Americans appease every single dictatorship and tyranny except North Korea, Iran, Bhutan, and Cuba. In fact, by this logic, the US “appeases” some of the most flagrant abusers of human rights and authoritarian governments, such as China, Russia, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, and Zimbabwe. Yet, cultivating a relationship with Cuba would somehow send a different message? Yes, Cuba may “scheme with our enemies,” Senator Rubio, but that hasn’t stopped the US from speaking with Russia (who supports Iran and the Assad Regime) or many other countries who aid and abet the US’s adversaries.

Why does Rubio’s fiery opposition to Obama’s policy change matter? Aside from asserting himself as a foreign policy leader in the Senate and winning conservative approval by berating the president, he isn’t exactly seeking constituent approval. Come 2016, his speeches might boast his consistent disapproval of Obama’s “naive foreign policy”; however, raising his head above the political parapet might not be advantageous with such a distant foreign policy issue. However, his role in the Senate has serious implications for the US’s new stage of foreign policy. Marco Rubio plans to not only derail Obama’s plan to lift the embargo, but also threaten to impede the funding of the new embassy and the appointment of an ambassador. With a Republican majority in Congress, it’s certainly possible Americans won’t see any move to lift the embargo, but Rubio might also galvanize enough support to challenge the president’s orders. As a rumored 2016 presidential candidate, his foreign policy matters and augurs badly for the future of US-Cuba relations. How might a Rubio presidency set back this diplomatic milestone? For now, however, Americans must hope that with US support, new infrastructure, technology and exposure will incrementally change Cuba’s social and political dynamic.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.