In the halls of Congress and the courts of public opinion, the battle of ideas and opinions raged between two camps: on one side, the interventionists, standing up for the ideal of liberty for all Mankind, and on the other, the noninterventionists, counseling prudence and moderation in all military affairs and undertakings. For across the ocean, seas of blood spilled across the plains of an ancient land embroiled in chaos.

In that ancient land, an oppressed people had risen up, casting off the chains of the oppressive dynasty which held them in subjugation. But their revolution had ended neither speedily nor happily. The forces of tradition and order had bounced back mightily, their iron fist seeking to stamp out the insurgency threatening their dominion. A long and bloody war had destroyed hundreds of thousands of lives, and threatened the stability of the region, while inspiring legions of foreigners to join to fight in the battle between Right and Wrong.

The Americans watched, horrified. The interventionist faction noted that the common cause of liberty bound together the Americans and the revolutionaries in the crusade to bring democracy to all Mankind. They advocated that the government of the United States provide any sort of support possible: troops, supplies, weapons, finance. Meanwhile, the noninterventionists, tempered by the experience of a recent war and a politically divided nation, counseled that the United States should avoid expending blood and treasure in a region where it held no vital interests.

The year was 1793.

Revolutionary France fought the first of its wars against the monarchs of Europe, and accounts of the death tolls were received by diverse opinions in the young United States. Some, including Jefferson and Madison, recommended entering the war on the side of France; others counseled against it. Ultimately, America abstained from entering the war and remained faithful to President Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation. But throughout the war, intense debate raged among the Americans.

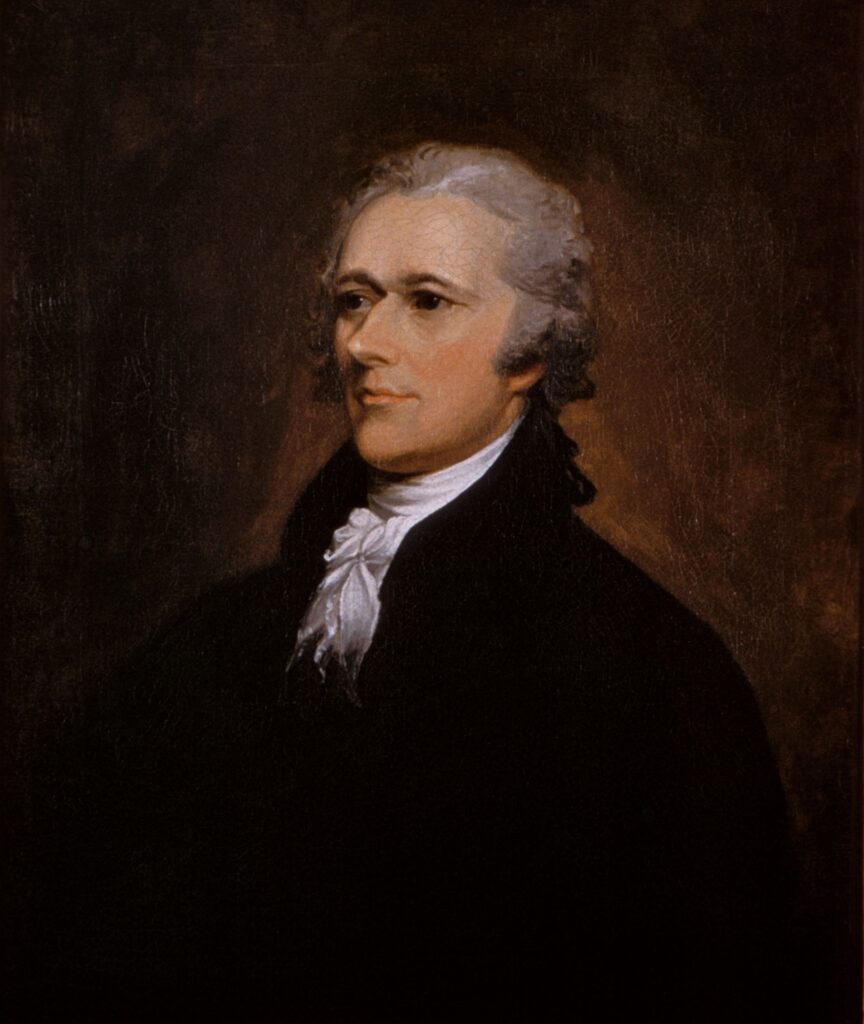

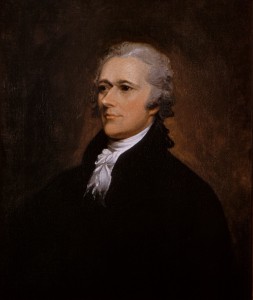

Presently, the United States finds itself in a situation with some parallels to that of 1793. We shall turn, then, to one of the most notorious and revered of the Founding Fathers, the most outspoken defender of the Neutrality Proclamation- Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton.

In his essay Americanus No. 1, Hamilton outlined two questions for the nation to consider:

“I. Whether the cause of France be truly the cause of liberty, pursued with justice and humanity, and in a manner likely to crown it with honorable success.

II. Whether the degree of service we could render by participating in the conflict be likely to compensate [adequately for]the evils which would probably flow from it to ourselves.”

Hamilton chose not to ponder the first question, noting that the values of liberty, justice, and humanity were so sufficiently subject “to opinion, to imagination, [and]to feeling” that proper policy could not be built upon them. Instead he focused much of his analysis on the second question, one of greater practical – and lesser moral – value.

The United States of 1793 possessed less than a third of its current continental territory, and was far weaker than the hulking superpower it has since become. The decision to exert force to alter the outcome of a great power war overseas was therefore a proportionally more costly exercise then than it is today. Hamilton noted America’s comparative weakness and additional problems of logistics, geography, and diplomacy which the voices of democracy had ignored, and counseled restraint.

Historical comparisons are never quite as similar as they might seem. But between the debate on intervention in France and today’s debate on intervention in Syria, a general principle holds as obviously in the 21st Century as it did in the 18th: there are those in the United States who see America’s foreign policy duty to uphold our values- to be that “Shining City upon a Hill,” and “to make the world safe for democracy,”- as outweighing our duty to maintain our concrete and measurable national interests. Although there is not necessarily anything wrong with a moral approach, and in fact much good in it, our statesmen today nonetheless must, like Hamilton, consider also the amoral and practical consequences of the policies they pursue.

Hamilton’s foreign policy advice continues to be useful to this day, and all crafting policy for the Syrian War should bear it in mind:

“…Let us not corrupt ourselves by false comparisons or glosses- nor shut our eyes to the true nature of transactions which ought to grieve and warn us- nor rashly mingle our destiny in the consequences of the errors and extravagances of another nation.”