On October 20th, two United Nation officials visited Detroit, Michigan to conduct an unofficial investigation into the water crisis plaguing the city. Catarina de Albuquerque, the Special Rapporteur on the human rights to water and sanitation, and Leilani Farha, the Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, stated that the ongoing water shut offs are not only a violation of human rights, but also disproportionately affecting the cities “most vulnerable and poorest.”

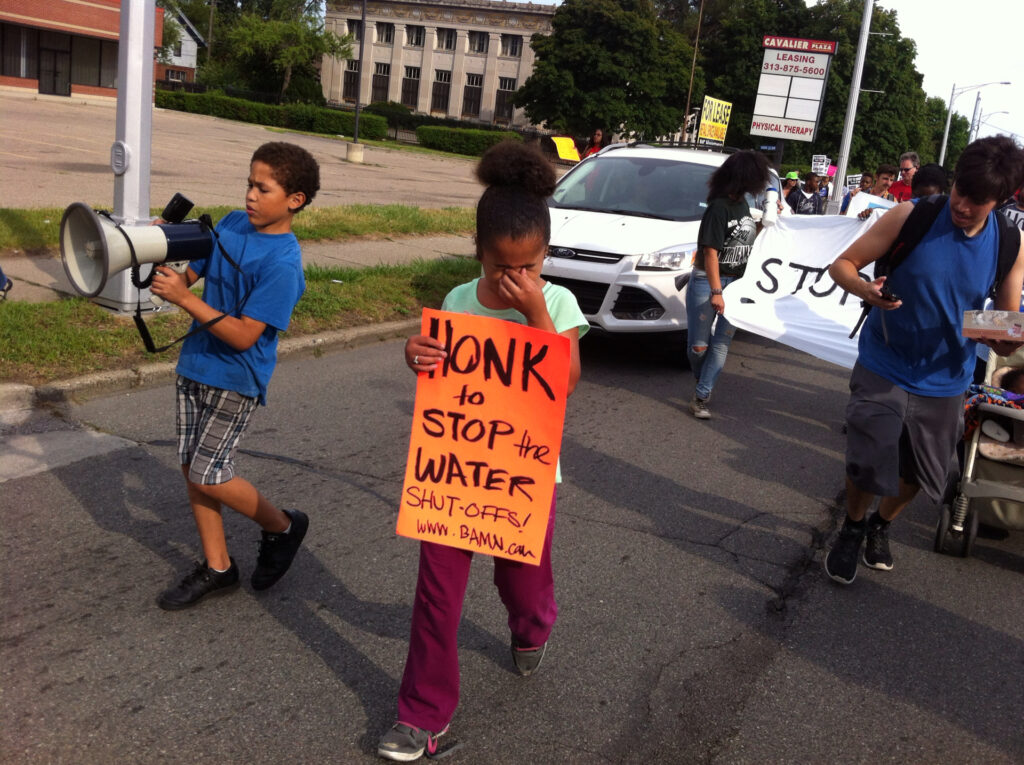

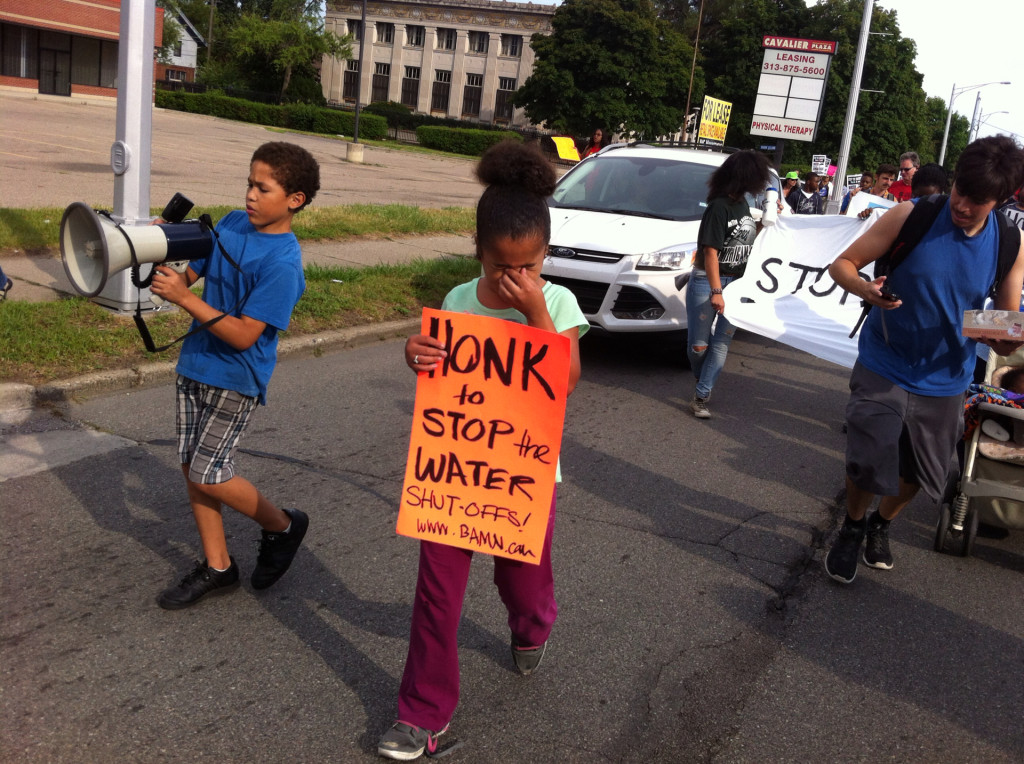

This past August, the city of Detroit shut off the water to thousands of citizens, with plans to cut off more than 100,000 citizens who are unable to pay their bills. The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department says half of its 323,000 accounts are delinquent, meaning that they have not paid bills that total above $150 or that are 60 days late. Additionally, since March, up to 3,000 account holders have had their water cut off every. The Detroit Water Authority justifies this stricter policy because of the estimated $5 billion in debt that the city now carries, which has sparked recent privatization talks.

The UN has declared that water is a universal human right. Resolution 64/292, adopted by the general assembly in 2010, “recognizes the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights,” and “calls upon States and international organizations to provide financial resources, capacity-building and technology transfer, through international assistance and cooperation, in particular to developing countries, in order to scale up efforts to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all.”

The UN made the claim that the federal government also has a responsibility to the people of Detroit. Leilani Farha, the expert on the right to adequate housing, expressed concern that children are being removed by social services from their families and homes because, without access to water, their housing is no longer considered adequate. She stated, “If these water disconnections disproportionately affect African Americans they may be discriminatory, in violation of treaties the US has ratified.” Catarina de Albuquerque, the expert on the human right to water and sanitation, stated: “I encouraged the US Government to adopt a federal minimum standard on affordability for water and sanitation and a standard to provide protection against disconnections for vulnerable groups and people living in poverty. I also urged the Government to ensure due process guarantees in relation to water disconnection.” They concluded that “the households which suffered unjustified disconnections must be immediately reconnected.”

Within domestic law, however, water is not a right, but rather a privilege only given to those who can afford it. US Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes refused to block the city from shutting off water to delinquent customers for six months, saying there is no right to free water and Detroit can’t afford to lose the revenue.

The problem in Detroit is that people simply do not have the means to pay their water bills. In a city where the median household income ($23,600) is less than half the national average – 38% of residents live below the poverty line and 23% are unemployed – it is not so surprising that 40% of customers are unable to pay for their water and sewage.

The noted absence of federal statements about the water crisis has promoted widespread international criticism of both the US and more specifically the city of Detroit. Having the UN conduct an investigation into an American city because people do not have water is not only an embarrassment for the country, but also a harsh reminder that even within a developed country like the US, there are those that are struggling for their basic amenities. While the water issues in Detroit are symptomatic of a wider city struggle from its past and current bankruptcy, their present predicament also brings to light the institutionalized racism that still exists in the US, the stratified and ever widening gap between classes, and the apathy of many Americans to crises at home. It was Canadians that brought aid to the citizens of Detroit, not Americans. It was the UN officials that stated water was a right for all people, not the US government. The water issues in Detroit have brought to light the not only the conflict between domestic and international law, but also the prioritization of human rights in American political and public discourse.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors, or governors.