LOS ANGELES — On July 11, thousands of Cubans took to the streets, eager for the liberty that decades of dictatorship and recent economic collapse denied them. According to reports on the ground, the Cuban government responded swiftly and brutally, leaving many citizens terrified to leave their homes for fear of arrest or worse.

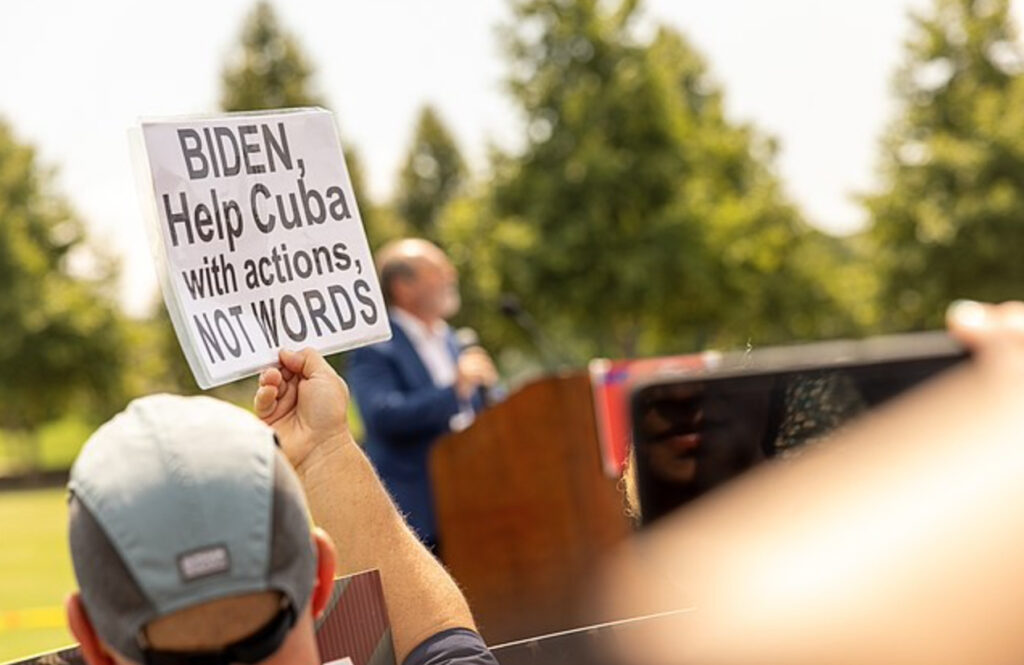

President Joe Biden and his political allies cheered on Cuban protesters for standing against “decades of repression and economic suffering to which Cuba’s authoritarian regime has subjected them.” But these protests, the largest the country has seen since 1994, emerged from much more than a slow-burning political dissatisfaction that finally boiled over.

The Cuban people needed to tell their leader and the world that they are hungry, dying unnecessarily and fed up with a government that seems impervious to their suffering.

The nation’s economy has suffered alongside the rest of the world during the pandemic, weakened by a drop in tourism and the subsequent decrease in foreign currency, which customarily helps consumers stay afloat. If COVID-19-related economic bubbles weren’t enough, Havana has also confronted financial mismanagement and crippling economic sanctions imposed by Washington.

Protesters and online critics claim there simply is not enough food to go around, and the sparse food remaining on market shelves requires hours of standing in line.

“Do you know what it’s like not to be able to buy my child food from the store?” Odalis, a 43-year-old mother in Havana, said to The New York Times.

Starving children, desperate parents, and an entire country in dire financial straits all face yet another crisis, a resurgence of the global pandemic. After months of keeping the coronavirus at bay, the national healthcare system has met its match in the novel Delta variant. Over the past two months, the number of positive test cases has increased by more than six times, and the medical system can no longer keep up. Hospitals lack sufficient oxygen and space to accommodate the drastic rise in cases, and people are dying at disproportionate rates as a result. In some parts of the country, death rates have climbed to eight times the average rate before the Delta surge.

The healthcare system has long been a source of national pride, with Cuban doctors living and working worldwide, but now, doctors at home claim that the system has buckled under the pressure of the pandemic.

“The funeral homes can’t cope, the hospitals can’t cope, the clinics can’t cope,” one doctor told the Times. Like many healthcare workers who have publicized the realities on the ground in Cuba, this doctor paid for the truth with his job. Despite the threat of job termination, detention and criminal charges, many Cubans have spoken up about their situations.

Cuban protesters succeeded in making their shouts heard around the world. Still, their leader has not only refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of their complaints but has actively attempted to suppress their protests, both physically and virtually.

Prior to the eruption of protests, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, Cuba’s first non-Castro leader in 60 years, conceded that the pandemic had overwhelmed the country’s healthcare system, but channeled the blame toward U.S. trade embargos, which he says exacerbate medical supply shortages.

President Díaz-Canel responded quite differently to the nation’s problems following July’s protests. The police crackdown arrived swiftly and firmly. Advocates estimate that as many as 800 citizens, including many underage, have remained detained for weeks. Many people have been arrested off the street, many claiming they had nothing to do with the protesters, and police have even begun going door-to-door to issue arrests, often without offering an explanation beyond “vandalism and looting.”

Days after chanting “libertad” in city squares, many protesters have taken shelter in their homes, fearful of losing their jobs and conflicted about speaking up in defense of those already detained for fear of exacerbating detainees’ treatment.

“The Cuban people are brave, but the repression right now is very strong and the effect is being felt,” said one distraught woman, regarding her husband’s extended detention. “There are still families who don’t know where their loved ones are.”

The crackdown on dissent is not limited to the spaces Cubans occupy at home and work but is also affecting online freedoms. Díaz-Canel issued sweeping legislation criminalizing any opposition to Cuba’s Communist Party on social media. The new laws forbid any content with the potential to affect “collective security, general welfare, public morality and respect for public order.”

The document clearly states its motivations as political, explicitly citing its purpose as “in defense of the Revolution.” Critics claim the new limits on freedom of expression are not only politically motivated but that the president deliberately designed the document’s language to be vague, allowing him to continue imprisoning and threatening any dissenters into silence.

The president had only recently authorized internet access, opening the island to online communities in hopes of modernizing the nation’s economy.

Many onlookers suspect this new window into the world beyond helped foment the protests on July 11, allowing Cubans to compare their empty supermarket shelves to those of their geographic neighbors.

A video of a small demonstration in San Antonio de los Baños circulated on Facebook earlier in the weekend and sparked protests in 25 cities around the nation.

Social media allowed Cubans to vent their anger and fan the fire until they gathered the collective energy to confront a government that had failed them. Díaz-Canel issued the new legislation in an attempt to squash communication and mobilization and, more personally, to silence Twitter’s favorite epithet for Cuba’s president “Díaz-Canel singao,” a term that combines derogatory and sexually explicit connotations and does not translate easily to English.

Díaz-Canel only officially took office as the first secretary of the Communist Party in April of 2021, years after being tapped to succeed Raúl Castro, finally bringing the six-decade Castro regime to a conclusion. Many younger Cubans had hoped their new president would guide the country toward more reform, continuing his predecessor’s advances toward privatization and diversifying the economy. Yet, these hopes have dimmed in light of the worsening economic crisis and social unrest.

Díaz-Canel’s decision to clamp down on dissent, both online and on the streets, will make it more difficult for Cuban citizens to make their voices heard. Still, many Cubans remain defiant, even in the face of so many parallel crises.

“These are laws to scare people,” said Norges Rodríguez, a Cuban telecommunications engineer and activist. “But on July 11, people came out to protest in a country where you can’t protest. I do not believe that a decree will stop the desire for freedom of a population that is fed up.”