Abstract

Despite friendly appearances, there is a growing policy gap between the US and the EU, be it in military capacity, attitudes towards China or trade and migration. In the past, the UK served as a bridge between the two actors through its special relationship with the US, but with the British leaving the Union, ties between the Western powers have weakened.

Given the importance of the transatlantic relationship, it is crucial that these two actors learn to cooperate and work as partners rather than competitors. Among the many points of tension, the issues of genetically modified organisms (GMO) regulations and data privacy are two areas in which the US and EU are prominently divided. However, unlike other spotlight issues, such as NATO or relations with the Middle East and China, they have fewer divergent opinions and more easily implemented solutions. Because of this, working to change policy in regards to these issues may be an effective step towards improving overall relations between the EU and US.

GMOs

Because GMOs are easier to grow, more robust to varying weather conditions, aesthetically pleasing, easier to transport, larger, nutritionally dense, cheaper to maintain and less perishable than normal or organic produce, the practice of genetically modifying produce has become more widespread. Yet this practice has been met with opposition because while there are obvious benefits to genetically modifying produce such as the increase in options and decrease in price, there are also concerns about the possible effects on the health of consumers, as well as the environmental impact.

In the United States, the general attitude is more accepting toward the production, sale and consumption of GMOs. Because of this, the US has fewer regulations and no specific policy to restrict the sale and consumption of these products. Furthermore, the US does not see the harm in continuing to produce GMOs, because while some believe that there may be adverse effects in consuming them, there have been no conclusive studies proving that they are indeed harmful. Because GMOs are easier to produce than non-genetically modified products, more companies have begun to adopt these processes and it has become a norm in the U.S. In fact, currently the U.S. has approved of 120 GMOs for cultivation while the EU had only approved seventeen.

Additionally, lobby groups in the agribusiness industry are extremely vocal and influential in shaping the U.S. policy stance on GMOs. In 2016 alone, the total spent on lobbying in this sector was $126,242,202. Because powerful companies and corporations like Monsanto have the resources to pour into successful lobbying, their objectives, such as ensuring there is as little regulation as possible on GMOs, get pushed most heavily.

On the other hand, the EU takes a more anti-GMO stance and has policies in place to limit the sale and distribution of GMOs. Traditionally more interventionist, the EU clashes with US vendors who try to sell GMOs to member countries. Not only does the EU have a slower and more restrictive process to approve of crops that can be sold in the marketplace, but it also requires mandatory labeling and full traceability of crops from the origin to the consumer, the farm to the final product.

The roots of the stringent standards on produce are about more than just concerns over general welfare. Certain causes of this issue lie within the EU political sphere, as the conflict over GMO regulation has become a proxy battle about leadership and legitimacy. Various actors within the EU have used the debate over GMO regulation as a means of furthering their own political clout, giving it a lot of attention, even if genuine concern about the issue itself is minimal.

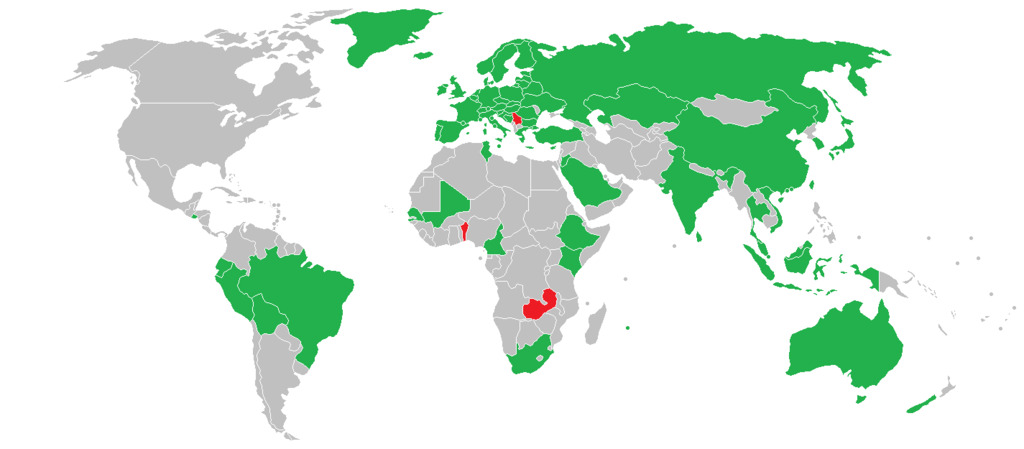

Furthermore, with the World Trade Organization supporting the stance of the US and the United Nations supporting the stance of the EU, the two entities have split the international community in terms of GMO regulation. Without a supranational organization to set worldwide standards, the US and the EU lack an arbiter to settle their differences and the division only continues to grow as the EU becomes increasingly stringent in its regulations.

Privacy Rights

Another point of tension between the EU and US concerns privacy rights and data protection. After 9/11, the US government adopted a much more proactive stance towards ensuring domestic security. In order to prevent future terrorism attacks, the government implemented several initiatives, like the Patriot Act, which gave the government relatively free access to its citizen’s information when national security is at stake. Although certain acts such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act exist to protect several areas of citizen information, there is no specific piece of legislation that protects privacy in general. Given the recent decision by the majority Republican Senate and House to approve a bill granting ISPs (Internet Service Providers) the right to sell user information, it seems as if the US is moving towards even more deregulation of internet privacy protection.

In contrast, the European Union protects the rights of its citizens’ right to withhold their private information except under the most pressing security issues. This protection explicitly applies to citizens withholding information from the EU, but it implicitly applies to entities outside the EU as well. However, the EU does not have direct control over other organizations so this mismatch of expectation and power to enforce it becomes a major point of contention.

The European Data Protection Directive, the EU’s formal policy on privacy rights includes a limit on international data transfers. This directive, passed in 1995, was one of the many steps the EU has taken to protect the privacy of its citizens. Since 2009, various organizations within the EU have taken further measures to extend and implement the protection of privacy. For example, in 2011, the European Commission stated that it planned to implement a regulation to harmonize data protection laws in Europe.

The conflict between the EU and the US arises from the fact that the US has harvested data of citizens of not only the US, but also of the EU. The U.S. government’s lack of a comprehensive stance on privacy rights has infringed on EU directives and caused the two entities to clash. Especially with the advent of the Internet, privacy issues have become an even larger point of debate. When Edward Snowden publicized information that exposed the NSA and FBI had direct access to information from servers like Google, many EU citizens were outraged as it gave U.S. governmental organization access to its citizens’ information without their knowledge and/or consent.

Towards A Reconciliation

In regards to the GMO issues, the EU and US can attempt to alleviate the source of this friction by implementing a two-part solution. The first step is to increase the amount and quality of research regarding the effects of GMO’s. Because the process of genetically modifying products is fairly recent, there is not enough reliable data to judge whether or not consuming and using GMOs has adverse health effects. The EU should partner with the US and pool resources in order to determine whether or not GMOs is truly detrimental to humans. Once reliable data is found, they should make sure to publicize this information so that the public can be duly informed and will not have unfounded fears.

The second step is to implement policies depending on their findings. If GMO’s do not have any adverse effects on people’s health or the environment, the EU should remove its ban on importing genetically modified products. This will improve relationships between the two countries and increase trade. If they do find issues regarding GMO’s, the EU and the US should implement policies to prevent these harms from reaching the public and limit environmental impacts. There should be and open dialogue and clear agreements should be made between the two entities. In addition, the EU should not necessarily act as a bloc in banning GMO’s. Member states should be able to implement their own standards regarding the imports of GMO’s, since this will provide more flexibility for the US to export and trade with the EU.

In regards to the issue of data protection from government encroachment (especially that of the US government on members of the EU), the US and EU should have open dialogue about their expectations regarding access to information of both citizens and national and supranational governments. Additionally, a revised Data Protection Regulation should soften requirements by handing the role of determination from the Commission to each member state. By giving member states the freedom to implement their own regulations regarding privacy rights, the EU and the US will have a less cohesive friction since issues will be between the US and specific member states rather than the EU as a whole.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.