Barack Obama’s historic trip to Cuba and the subsequent easing of relations has left Cuban and US scholars wondering if this is the beginning of the end for the Cuban Embargo. Since Raul Castro’s ascendence to the presidency, change has been in the air; Airbnb, privatized farms, and joint ventures in biotech have led the gradual trend of reform and marketization after a long period of depressed growth in the post-Soviet 90s. But even as American tourists pour into the country, and Cubans leave the state-sector for newly sanctioned private enterprises, and upper-class, LA-style cafés and brunch joints fill into Havana’s fashionably dilapidated colonial house interiors, it’s important not to get swept up into a melodrama of development. The state and state monopolies still govern the fundamental details of Cuban life, internet is barely there, shortages are frequent, and most who graduate from college must decide whether to take a low wage government job, or work as a tour guide or waiter at a private restaurant.

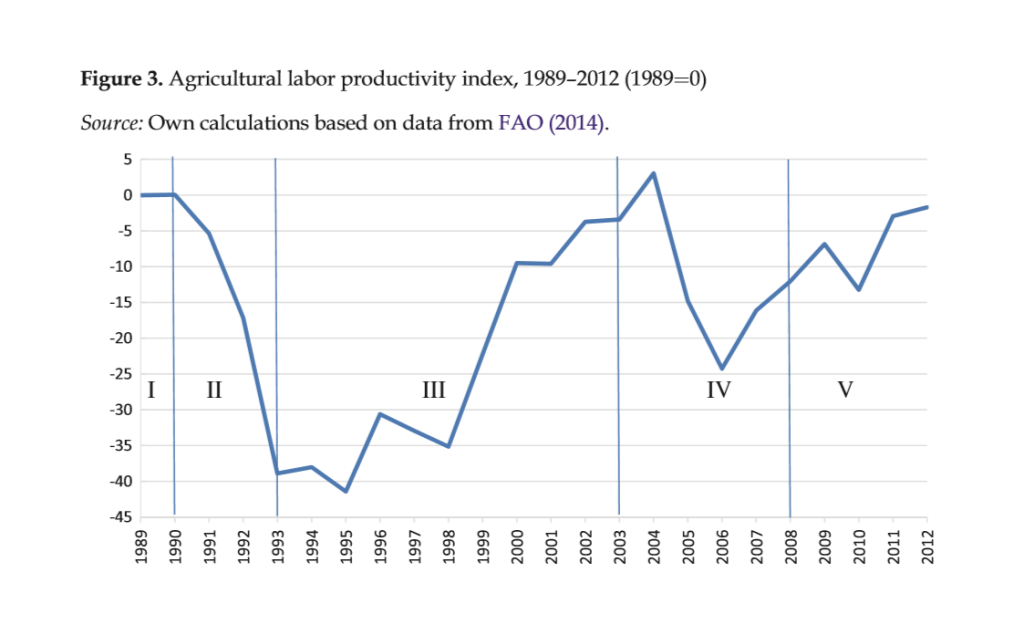

The state of agriculture is a great case study in the mixed results of Cuba’s reforms under Raul Castro, the hopes of ambitious entrepreneurs posed against the slow machinations of the regime. Since the collapse of the USSR, Cuban agriculture has suffered from low labor productivity, insufficient output, decapitalization and inefficient organization. The resulting food security crisis pushed the government to break-up poorly managed state farms into medium-sized cooperatives called CPAs and UBPCs (“basic units of cooperative production”) that were relatively more efficient, at about 10% the size of the original farms.

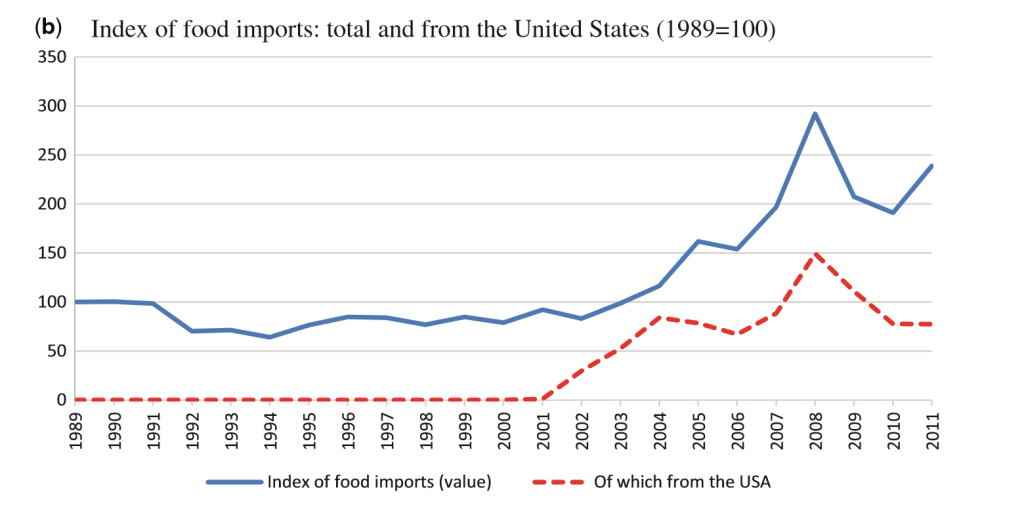

While by 1996 Cuba saw a moderate rise in non-sugar agricultural production, a lack of capital, inputs and processing organization meant Cuba still suffered from extensive food shortages, and had to import 80% of their food through the early 2000s. Though UBPCs were better than state farms, they still suffered from bureaucratic government administration, with no freedom in purchasing imports or labor for themselves.

| Year | Total Agricultural Land (in 1,000 hectares) | Private Land (in 1,000 hectares) | Total Non-State (in 1,000 hectares) | Private Land as % of Total Land | Private Land as % of Non-State Land |

| 2007 | 6619.5 | 1214.3 | 4899.7 | 18.34429 | 24.78315 |

| 2012 | 6405.6 | 2479.5 | 4398.8 | 38.70832 | 56.36765 |

| 2013 | 6342.4 | 2291.7 | 4490.7 | 36.13301 | 51.03213 |

| 2014 | 6278.9 | 2227.9 | 4336.3 | 35.48233 | 51.3779 |

Data from ONEI (2014)

The transition to private and small cooperative farms has brought with it a radical shift in average farm size. Where a state farm producing vegetables and roots could average 4,200 hectares, a UBPC collective averages closer to 460, and a private farm only about 16-65 hectares. The return to the family farm model is believed to be key in the current boost in agricultural yields—smaller plots means less managerial costs, more crop-mixing and more labor intensity per hectare, which in the development literature translates into improved labor productivity, more bang per buck.

Usually these changes, which amounts to a massive decollectivization in Cuba, bring with them increased mobility, freedom, profit and quality of life for the independent farmers who can now work their own land, sell their own surplus and begin to accumulate savings beyond the meager wages offered by the state. So why is the majority of food that Cubans consume still coming from the US? Why isn’t total cultivated area in Cuba growing? A number of challenges are still holding farmers back, and preventing improved productivity from translating into real, tangible economic gains:

- Tenure insecurity— Because the Cuban government reserves the right to expropriate farmers from lent land if deemed unproductive, usufructary farmers suffer from intense tenure insecurity, which prevents them from making important investments in the land needed to boost production.

- Capitalization— Buying irrigation and farming equipment requires start-up money, which the state doesn’t provide. This issue is closely tied to Cuba’s dramatically low wage rates, which mean that family members who work off-farm often can’t make enough money to begin the process of capital investment.

- Inputs — Input markets for equipment are organized by the state and often too expensive to access. Certain imports such as diesel or some bio-fertilizers are quoted in CUC, Cuba’s convertible currency, which is valued much higher than the peso farmers are payed in, the CUP—expensive inputs render more serious yield improvements impossible.

In 2012 and 2013, the government took a number of steps to address some of these small farming issues. The granted plot size rose from 13.4 to 67.1 hectares (165 acres) as long as the usufruct recipient was linked to a cooperative or state farm (it was clear the government had gone too small on land grants, providing too little area for sustainable production). The usufructuary was granted permission to build homes and plant orchards on the land. Also, if the contract is not renewed after 10 years, the state is required to evaluate the farmer’s investment on the land and reimburse him. Relatives are able to inherit a plot if a farmer dies during his contract. Usufructuaries were granted a two-year exemption on personal income tax, and land value tax. But none of these reforms seriously address several major problems in Cuban agriculture: the centralization of inputs in state-run markets, the inability for individual farmers to independently hire labor, and the inability for usufructuaries to rent out land [2].

Policy

- More robust improvements in agricultural yield and cultivated land growth will come from a dramatic liberalization of the market for agricultural inputs, the market for land, as well as a reduction or eradication of the state price system (channeling Vietnam) that delivers quota requirements to individual farms (the so-called acopio system). We’ve seen some success in the expansion of domestic food markets through farmers’ markets in Havana. The next step here is to begin to relax the complicated licensing measures required to sell agricultural surplus in the city. There is also ample opportunity to begin to integrate local food products into the major grocery chains within the country, instead of importing the majority of grocery products. This gradual strengthening of market linkages and private networks will naturally erode the state-centric acopio system of food purchasing.

- In terms of improving tenure security, while the government has already taken steps to improve legal protections and promise of compensation for expropriation, the next natural move would be to lengthen licenses for idle land from 10 years to 20 or 30 years, as is already being done for larger cooperatives.

- In order to stimulate further investment in the land and improve migration into the agricultural sector, the government must begin to offer incentives beyond tax write offs to spur investment in infrastructure and physical capital that will produce long term yield improvements. This includes offers of capital for building homes and barns on the land, in order to improve rural linkages and allow newly landed farmers to organize their household around the farmland for the long term.

- Decollectivization may not in fact have to be actively mandated, as long as the government allows current usufruct farmers to begin to consolidate and improve their holdings, and begins to offer cheaper alternatives for input purchase and capital accumulation we will see interest in independent farming grow. This means allowing farmers to determine their own output levels, the destination of their products and allowing independent farmers to begin to hire their own labor throughout the season so that they can begin to increase their output and cultivated area.

Watching Grass Grow

When South Vietnam was integrated into the communist regime, southern farmers were gradually transitioned to a collective farming system at the expense of rice productivity. As in the Cuban case, many cooperatives involved farmers pooling their land and tours, and sharing output based on time spent working. The poor incentive structure brought on by the high costs of monitoring performance depressed rice production –cooperative farmers had a 52% lower productivity than non-cooperative farmers. An initial attempt at decollectivization suffered from the same tenure security and incentive issues as in Cuba. It wasn’t until the Vietnamese government pushed a more radical set of reforms and liberalizations which included guaranteed compensation for farmers displaced from their assigned land, the privatization of output markets, ending the required sale of food to the state, and a decentralization of input supplies and input markets that Vietnamese agriculture bloomed [3].

But radical isn’t really the style of the Cuban dictatorship, whose bureaucracy is deliberately designed to articulate power and obstruct change through sheer largesse and inefficiency. Periodic food shortages, ration books and state pricing are all important parts of a strategy that has kept the Castro’s (along with the military and industry elites) afloat since 1959, and will continue to support whoever else is in charge come “elections” in 2018. Change will come from the people, the urban farmers, the entrepreneurs and biotech scientists who come up with new ways to make do without tractors or fertilizers, who fight food insecurity with organic, family farming methods, sell their surplus in the city to a blossoming network of private restaurants, cafes and farmers markets, while quietly (at first) grumbling to each other about the state’s violently out-of-fashion food monopoly.

[1] Riera, Olivia and Jonah Swinnen, “Cuba’s Agricultural Transition and Food Security in a Global Perspective,” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 38.3 (2016) pp.413-448. [2] Gonzalez, Armando and Mario A. Gonzalez-Corzo, “Cuba’s Agricultural Transformations,” Journal of Agricultural Studies, 3.2 (2015) pp. 175-180. [3] Pingali, Prabhu and Vo-Tong Xuan, “Vietnam: Decollectivization and Rice Productivity Growth”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 50.4 (Jul 2992). Pp. 697-718.The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.