For most of the American foreign policy commentariat, myself included, the greatest and most horrendous legacy of a Trump Presidency was always going to be President Trump’s clownish mismanagement of foreign affairs, which many believed would lead to a breakdown in international order and the final end of the liberal international system. Trump’s election, and subsequent appointments of General Michael Flynn and Steve Bannon to the high positions within the White House, seemed to validate those concerns.

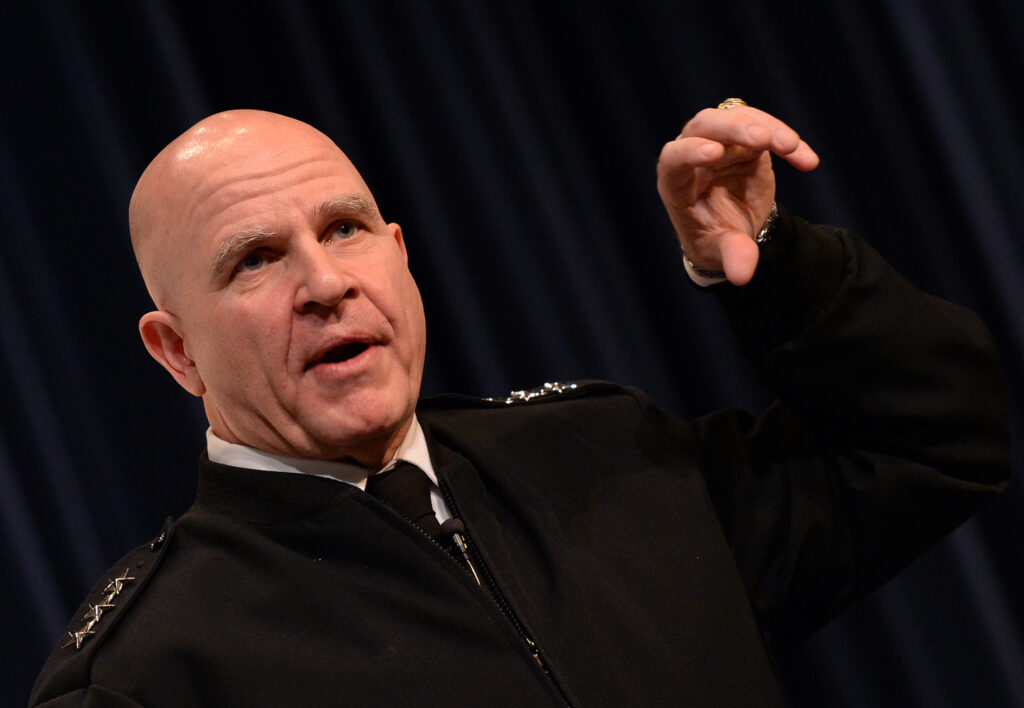

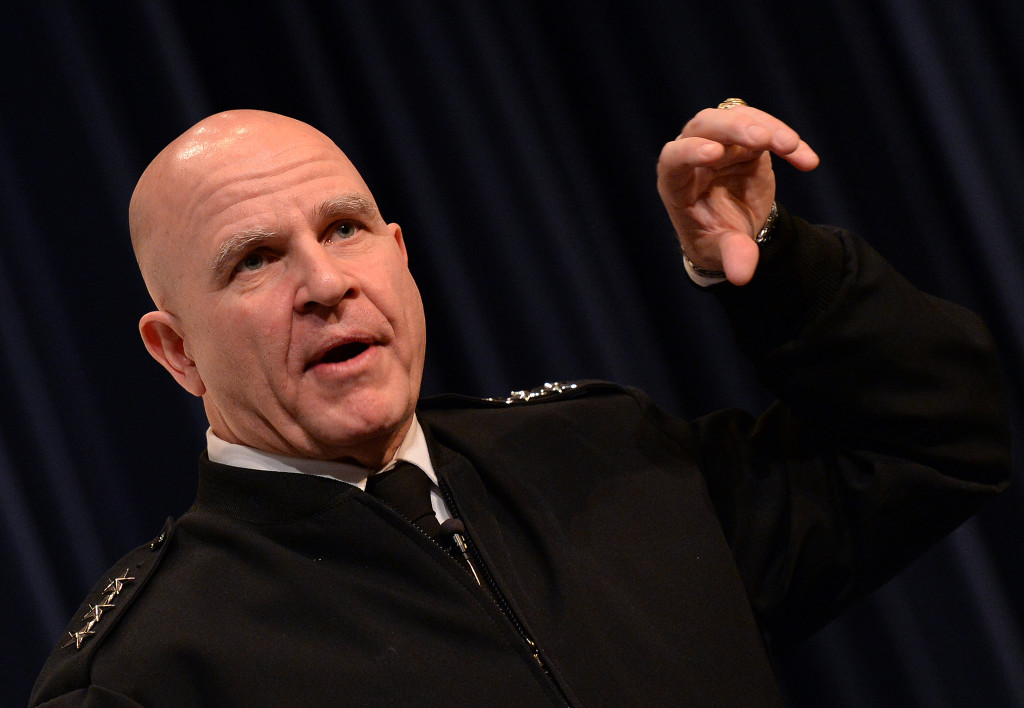

Those concerns still might be valid, just as concerns about the President’s seemingly-schizophrenic temperament, neurotic Twitter habits, and lack of formal experience in politics and foreign affairs certainly remain valid. But there is an increasing body of evidence that the Trump Presidency might be far less interesting, or indeed far more beneficial, for American grand strategy than anyone could have assumed going into it. High-level appointments like Secretary of Defense James Mattis, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster, and the serious consideration of figures like General David Petraeus and Ambassador Jon Huntsman for roles within the administration, indicate a strategic sobriety and realism within the Trump Administration’s vetting team, perhaps within the mind of President Trump himself.

With Mattis, Tillerson, and McMaster steadying and guiding President Trump’s strategic hand, we very well may see the resurgence of American realism going into the third decade of the 21st Century, not unlike previous resurgences across American history.

What is American Realism?

As many students of American foreign policy and international relations argue, Theodore Roosevelt was the American realist-internationalist of the 20th Century. (Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, and perhaps George H.W. Bush are on the second tier.) TR’s political philosophy of individual excellence and patriotic citizenship was intrinsically and inescapably linked to his philosophy of national greatness on the world stage. But his philosophy of national greatness was not Wilsonian- he neither sought to “make the world safe for democracy” nor to “teach [other countries]to elect good men.” His sole concerns were the interests of the American nation and the American people, and the construction of such a balance of power and liberal world order as could best preserve those interests in a way compatible with American values.

Theodore Roosevelt saw a world of rising great powers and increasingly complicated social and economic trends, and saw that the preservation of American liberty and union required a stronger American commitment to international affairs and world order than American politicians had theretofore allowed. This competitive and complicated new international system, and America’s yet-undefined role in it, required cold prudence in statecraft and basic unity of American national purpose, which TR provided during his tenure as President of the United States.

This sensibility has guided American statecraft countless times over the last century. Whenever America has forged a durable and sustainable international role or world order, there has been a generation of capable realist-internationalist statesmen at the helm; this has been especially crucial at times of global power transitions like that of the late 1940s. We got lucky with generations of such leaders twice, and were less lucky as the Cold War progressed and ended. Now, as we exit the Post-Cold War and enter a new Age of Nationalisms, we could use quality leaders of realist-internationalist leanings again.

But first, a look at the older generations and their power transitions.

Teams of Realists at the Power Transitions

The first major reshaping of America’s role in the world came around the late 1890s and early 20th Century, when America formally shifted from its “Promised Land” role to its newfound “Crusader State” position (to cite Walter McDougall’s parlances.) Warren Zimmermann documents the contributions to this new American imperialism and internationalism through a study of the lives and friendships of Theodore Roosevelt, John Hay, Henry Cabot Lodge, Alfred Thayer Mahan, and Elihu Root, in his book “First Great Triumph: How Five Americans Made their Country a World Power.” This post-Civil War generation of American elites were temperamentally conservative but politically nationalist and internationalist- “Neo-Hamiltonians,” as Samuel P. Huntington described them. Their contributions came at a critical time, and helped position American internationalism at a moment when it was most needed. Post-World War One elites like Woodrow Wilson were not nearly so successful, and even Franklin Roosevelt’s Cabinet during the Second World War did not have so lasting an influence, brilliant though they were in prosecuting the war and defeating the Axis Powers.

After the close of the Second World War, a major debate cropped up concerning America’s future role in the postwar/early Cold War world. As usual, isolationists and America Firsters made themselves heard, but the debate was ultimately dominated and won by a group of six friends who managed to convince President Harry S. Truman to assume an internationalist, “Cold Warrior” stance of containment of the Soviet Union and the formalization of a liberal international order featuring permanent alliances. Walter Isaacson depicts the lives and contributions of Dean Acheson, George Kennan, Averill Harriman, Robert Lovett, John McCloy, and Charles Bohlen, six friends and the first Cold Warriors, in his book “The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made.” Their contributions committed America to its postwar internationalist global stance, and effectively set the tone of world politics throughout the six-decade span that would become known as “The American Century.”

Both friend groups were composed of what were once known as “WASPs,” or White Anglo-Saxon Protestants, typically upper-class Northeastern Puritan-descended American elites who were bred into a cult of duty to the nation. They had their flaws, and after the 1970s ceased to exist meaningfully in American culture, having been replaced by new generations of self-made, cosmopolitan men and women. But their Neo-Hamiltonian, realist-internationalist temperament and sense of public duty has since proved less common amongst our elites than it once was, and I would argue we have suffered because of it.

The next great realignment of America’s role in the world occurred in the 1970s, amid the splitting of the Communist Bloc, the return to prominence of Europe and Japan, and the “rise of the rest” of nations in the developing world. But no elite of WASP-y thinkers rose to manage the transition of American foreign policy to a new world; instead, the most unlikely of duos, the anti-establishment grocer’s son, President Richard Nixon, and his partner, the Jewish immigrant-intellectual Henry Kissinger, shaped American foreign policy for a multipolar age. They achieved some basic strategic successes, but ultimately failed to shape the future development of U.S. grand strategy much- perhaps because they never institutionalized a new foreign policy social elite.

The next great realignment was incomplete. When the Soviet Union collapsed, President George H.W. Bush and his main advisors, Secretary of State James Baker and National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, steered the ship of state through potentially tumultuous waters with Kissingerian cunning and prudence. But Bush and company never managed to institutionalize a Post-Cold War grand strategy, again perhaps due to their failure to set up a new social elite capable of steering foreign policy.

So despite the grand strategic successes of the Nixon-Kissinger and Bush-Scowcroft-Baker teams, the basic timbre of Post-Cold War American grand strategy was set by a distinctly different social elite- the cosmopolitan, liberal internationalist Democrats who had been shaped by the Antiwar movement of the 1970s, and their neoconservative counterparts in the Republican Party. The subsequent incoherence of American grand strategy from the Clinton liberal internationalist years through the “Vulcan” Bush 43 years through the Obama retrenchment-lite years is testimony to President Bush 41’s failure to institutionalize American strategic discipline a quarter-century ago, regardless of the brilliance of his other victories.

The Need for Enlightened Elites

As James Burnham argued in “The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom,” political science is in many ways merely a study of the values of, behavior of, and constraints upon socio-political elites. And the Post-Cold War American elite clearly failed to conduct American foreign policy responsibly enough to perpetuate itself beyond 2016, losing the Presidency then to the incoherent populist Donald Trump. President Trump, despite Niall Ferguson’s high hopes for his Presidency, does not seem to be a reformist strategic thinker. There is reason to expect that his Presidency will result not in a major realignment in American strategic thinking, but in a need for such a realignment, to cope with the international disasters this administration may well accidentally bring forth.

But then again, Tillerson is Secretary of State. General Mattis and General McMaster are sane and competent strategists. General Flynn is out, and Steve Bannon might not survive the duration of the administration. There are responsible adults in the managerial apparatus of American foreign policy, at the very least. Perhaps these realist-internationalists will temper the impulses of the President and provide strategic thinking where there would seem to be none.

Perhaps Trump has brought to power a new foreign policy elite of responsible realist-internationalists, with a WASP-y culture of service and duty ingrained in their souls, to manage world order. It is too much to expect of our present situation that this “Team of Realists” will be capable of perpetuating itself into the further future the way Mahan and Lodge or Kennan and Acheson did; but even if we have merely a strategic management team like the Nixon-Kissinger Duo or the Bush-Scowcroft-Baker Trio at the helm for a mere four years, there is untold good that can be done.

It’s too soon to rest easy. We still don’t know what influence the cunning Steve Bannon will have over the Administration’s foreign policy, if he stays onboard. Plenty of commentators have suggested that Tillerson isn’t quite up for the job of Secretary of State. And there’s no guarantee that Trump, who routinely attacked “the generals” on the campaign trail, will listen to Mattis and McMaster on important questions of war and peace.

But the very fact that these voices have now been formally placed in positions of high office means that they’ll have, at the very least, a chance to influence the process. A new age of American Realism may well be upon us.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.