Alma Velazquez

The disheartening outcome of the Colombian plebiscite is another example of a common negotiation pitfall: two-level games. Ending Colombia’s century-long conflict with the FARC may involve mostly domestic players, but it is expected to please both an opposition entity (FARC rebels) and a divided domestic constituency. This duality keeps negotiators from reaching a deal amenable to both. In this case, the divide among “yes” and “no” voters is telling of a much larger issue.

The distribution of “no” voters highlights a persistent malaise endemic to not only Colombia, but Latin America as a whole: staggering inequality. The “no” campaign was led by former president Álvaro Uribe and a conservative landowning class. The position of these political leaders has always favored a military defeat of the FARC, and rejects the deal on the grounds that impunity cannot be awarded to terrorists. However, because the deal allows the FARC congressional seats and outlines a commitment to the equitable restructuring of Colombian society (especially as relates to the rural poor), the far-right landed elite also fear a loss of political power. Furthermore, the geographic distribution of votes shows that those most affected by the armed conflict—largely the rural poor and indigenous departments of the country—voted overwhelmingly in favor of the peace deal.

Highlighting this great divide confirms that even if a peace deal is eventually passed, it will only be the beginning of a long process toward inclusivity. Some experts believe that it was the armed conflict that kept protests and social demands at bay—it was simply too dangerous to speak out, allowing issues like land reform to go unaddressed. As a consequence, inequality and concentrated land ownership persisted.

Luckily, despite the resigned claim that “there is no plan B,” both sides have declared they are still committed to pursuing peace, and that the ceasefire still stands.

Miles Malley

For the second time in a bit more than four months, the result of a national referendum has shocked the world. There are several similarities between the two. In both cases — Brexit and the now failed Colombian peace accord with FARC — the side led by emotion and anger, albeit due to legitimate griefs, narrowly defeated those guided by rationality and compromise. As with Brexit, a lack of voter turnout may have played a decisive role in Colombia’s referendum, with only 37% of the electorate bothering to vote. Both instances saw the country’s leaders at the time, Prime Minister David Cameron and President Juan Manuel Santos, as well as the vast majority of experts, finding themselves on the losing side of the plebiscite.

But what distinguishes the two is far more concerning for Colombia: for all of the EU’s faults, it hasn’t been responsible for the murder of approximately 220,000 people and the displacement of millions more. Thus, not reaching an agreement with the EU doesn’t leave thousands of lives hanging in the balance — failing to reach a deal with FARC does.

Both FARC leaders and President Santos, who had been in negotiations for four years, have repeatedly claimed that there is no Plan B to these negotiations. Those who rejected the peace deal under the belief that FARC will be forced to come back to the table with tougher terms will soon unfortunately, devastatingly, find out that the alternative to this peace deal was, and now is, continued conflict and bloodshed.

Andre Gray

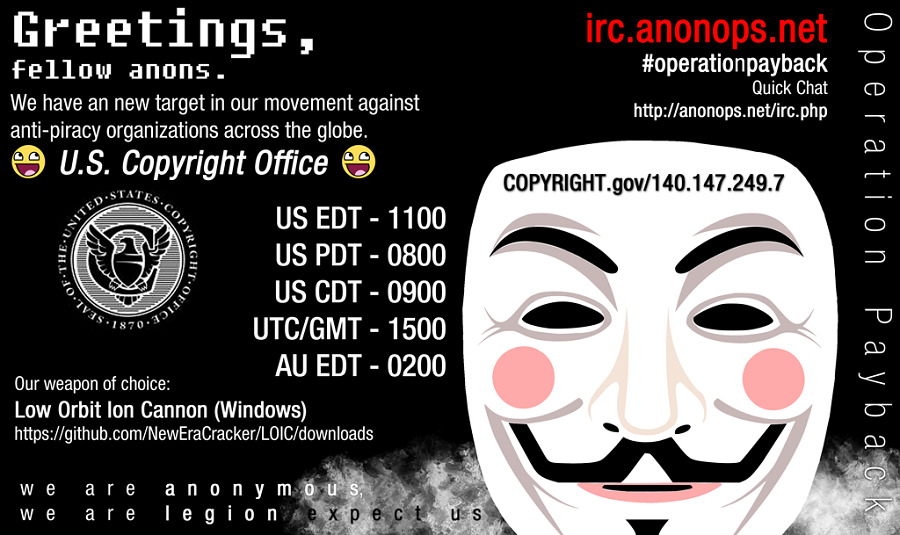

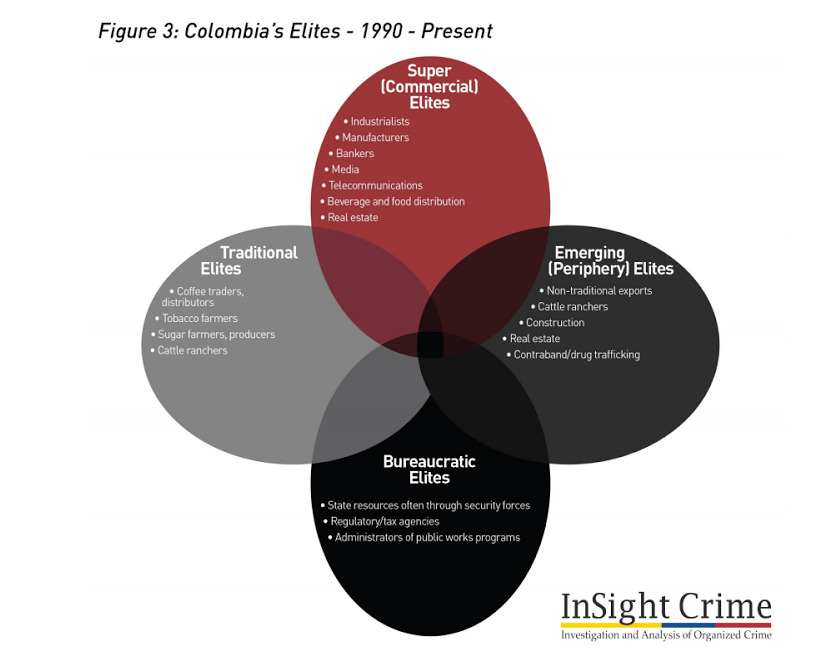

Who owns Colombia? The slim win of the “No” vote will likely be investigated in the coming weeks for foul play. This is a movement organized around former president Álvaro Uribe, a landowner’s son responsible for the scorched-earth policy against the FARC that displaced masses of rural poor, and whose various ties with Colombia’s right-wing paramilitary groups (responsible for about 80% of the civilian deaths during the war with the guerillas) make him the criminal bastion of Colombia’s modern “narco-capitalist” elite. Propelled into wealth by the rise of drug-trafficking in the 80s, the narco elite bought their way into the landowning class by purchasing ranch land for cheap from people fleeing the guerilla war. Since then, these forces have consolidated their power and infiltrated the government at all levels. As of 2014, 61 members of Colombia’s Congress had been convicted for ties to the paramilitaries, and another 60 had been investigated. These were largely allies of Uribe. Despite the reorientation of the Santos government towards peace, it’s clear that right-wing paramilitary groups, in alliance with large landowners (note that the top 1% of landholders own half of Colombia’s agricultural land) still have a powerful hold on Colombian politics, and would like to continue to thrive under a state of perpetual war.

Katya Lopatko

More shocking than the Colombian people rejecting a hard-brokered peace for their ravaged country is the fact that only 38% of the electorate participated in the referendum. Doubtless, granting amnesty to the people who have terrorized them for decades and murdered their friends and family is a hard prospect to swallow for many Colombians. And yet, one would think that most would hold strong opinions one way or the other on an issue so critical to Colombia’s future and even survival.

Regardless of whether these disheartening statistics came about due to public apathy, institutional or logistical barriers to voting or some other factor, the reality today is that Colombia’s future has been thrown into serious peril by a difference in opinion of less than a percentage point among just over a quarter of the population. The world waits breathless to see how FARC and Santos’ government will proceed with negotiations — if talk of “no plan B” was a tactic to gain voter support or if there really is no alternative than return to full-blown war.

Luke Phillips

Anyone concerned about American continental security ought to be concerned, at least a little bit, with the happenings in Latin America, the American near-abroad- from political instability in Venezuela and Brazil to the simmering low-scale wars in Mexico and Colombia to the lingering authoritarian regime in Cuba. The recently-rejected peace deal between Colombia’s Santos government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) should tell American strategic planners one major thing—regardless of the situation on the ground, and regardless of the intentions of political leaders, the Colombian people do not think that the region’s drug insurgency has ended. The Santos government’s mandate has effectively been rejected by the public, and whatever peace has been reached will be fragile at best, and unsupported by many Colombian citizens.

This doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that decades of U.S. counterinsurgency aid to Bogota has been wasted. The very fact that any kind of peace deal has been reached suggests that the security situation on the ground is better than it was in, say, 2006-2008. Rather, the referendum ought to be seen as a vindication of the elusive nature of peace, and the necessity that problem-solving statesmen and stateswomen win the political battles at the same time as they win the strategic battles, if agreements are to mean anything.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.