Russian President Vladimir Putin once remarked, “Sometimes it is necessary to be lonely in order to prove that you are right.” Putin has not shied away from unilateral action and is proving to be a calculating realist leader who is readily attempting to increase Russia’s power. The most notable example was his successful annexation of Crimea and destabilization of an anti-Russian, pro-West Ukrainian government to the benefit of his domestic popularity and Russian strategic posture. Russia did lose global popularity, but the incident confirms Putin’s preference for realist considerations of relative power over neo-liberal concerns of interconnectedness and positive foreign relations, which he unabashedly sacrifices. He is at it again by intervening in Syria, currently in its fourth year of a bloody civil war.

After Russia’s parliament unanimously approved of further military action in Syria, Moscow has dramatically increased its military presence in the Mediterranean base of Tartus, which they lease from Syria, and began airstrikes against ISIS as well as US-friendly rebel groups. Russia is laying the groundwork for a major Russian intervention despite the vehement opposition of the US and Europe. Their strategic move in the area maintains Moscow’s regional relevance and tilts the Middle East back in their favor geopolitically. Putin recognizes that winning the Syrian Civil War means winning the region.

Firstly, in order to establish Russia’s interest in the region, we need to look at the historic and long valued Russian-Syrian strategic relationship going back to the 1950s. Syria was ruled by a socialist (and nationalist) Ba’ath party that required assistance in governing a state in a volatile region. The Soviet Union was more than willing to step in, and the strategic relationship has been a match made in heaven since then, eventually including cultural exchanges and international marriages. When it comes to direct national security interests, Russia’s only base in the Mediterranean is in Syria, making it the lynchpin of Russia’s regional military and economic power projection, and of achieving Putin’s ambitions to increase Russia’s global clout. Additionally, amidst the political instability and many powerful non-state actors in the Middle East, the Assad regime provides critical regional intelligence to Moscow. This partnership has historically been the counterweight to the US and Israeli Mossad’s relationship.

Secondly, Russia’s involvement in the region is an extension of their national security interests; namely, ISIS and similar extremist organizations (e.g. Al-Nusra Front) are seen as a major threat to Russian stability. More than 2000 Russians have joined ISIS thus far and on October 31, a Russian airliner flying from the Sinai Peninsula was brought down by an ISIS bomb. Unlike the US, which is insulated by distance and two oceans, Russia’s southern border is relatively close to the region and the risk of an ISIS attack on their territory is higher. ISIS has exemplified their ability to launch terrorist attacks in the recent Paris attacks, there are videos threatening more impending attacks in Russia and there is a homegrown Islamic separatist movement in Chechnya, where many terrorist plots trace their roots. With these strategic interests in mind, Russia has wielded its veto power in the United Nations Security Council to prevent any UN-sponsored intervention or condemnation of the Assad regime—a crucial ally and partner in the fight against Islamic extremism. They have also continued their decades-long practice of supplying weapons to Damascus in order to equip Assad’s Army to effectively fight extremists and rebels, despite criticism that the arms are also being used to commit human rights violations. Now with the situation on the ground becoming more perilous and tense, direct military involvement is a natural escalation of Russia’s involvement in the region.

In addition to simply maintaining historical interests and security, Putin likely sees intervention in Syria as an open door to extend Russia’s reach and influence. There is a hegemonic vacuum in Syria: no major power is doing anything particularly meaningful to change the situation on the ground. The US is engaging in airstrikes, dropping ammunition relatively haphazardly (amid reports of not properly vetting the recipient organizations) and training rebels with very limited results. On the other hand, Russia’s air strikes, missile launches and artillery barrages are coordinated with a ground offensive composed of the actions of the Syrian Armed Forces (SAF), Hezbollah and Iran, which has reportedly led to initial success. There is no doubt that ISIS and the various rebel groups are powerful, but it is hard to imagine them winning a direct confrontation against a Russian-backed, three-pronged attack by the SAF, Hamas and Iran. What makes Russian operations easier is that they have a clear strategic goal: defend Assad and defeat both rebel groups and the Islamic State. On the other hand, the United States is in the strategic quandary of balancing opposition to Assad and opposition to ISIS. Since defeating one necessarily strengthens the position of the other, a substantial US intervention is unlikely.

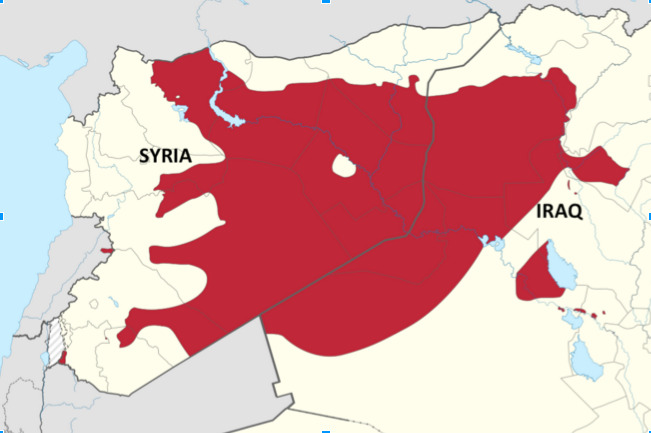

Given the lack of meaningful opposition to Russian-backed forces in Syria (excluding rebel groups and ISIS), it is critical to consider the scenario of a pro-Assad victory and what it means for the region. Islamic State administers the area east of Damascus all the way to central Iraq as an internationally unrecognized country.

This gives the Russian-backed forces the ability to operate freely in the northern Middle East without the headaches of breaking international law regarding the infringement of state sovereignty. To add, Russia has token legitimacy—they even have the approval of the Iraqi government to intervene in what used to be their northern territories. A victorious Assad and Hamas backed by Russia would only have Kurdish and Iraqi forces as competitors in the area. While the Kurds are formidable, they do not have a recognized state, no regional allies and only the distant US to provide them with inconsistent aid. The Iraqi military has proven impotent and their government, headed by Prime Minister al-Abadi, has drifted away from US influence and is increasingly prone to co-option by Iran.

An Assad victory and the defeat of ISIS in conjunction with stronger Iranian influence in Baghdad would mean a potential Shia corridor in the central Middle East region. Russia would benefit at the very least by seeing the region swing further away from the US, which historically sides with Sunnis. Given a more generous victory, the Russian Federation has the potential and the ability to extensively shape the region in any post-war settlement through proxies – similar to their influence in central Asia and Eastern European states like Belarus – and in turn benefit from the northern corridor of Middle Eastern oil. Russian conglomerates like Gazprom and Lukoil already have operations in Iraq and Iran. With their alliance with Iran and Syria, along with a teetering and vulnerable Iraq, Russia can create a strong connected bloc of friendly nations. This is assuming, of course, that they win the Syrian Civil war and that the United States continues to maintain a relatively aloof strategic posture.

Russian involvement in the Syrian war marks the first overt Russian military campaign outside of the former USSR in 36 years. It is not a haphazard move, but rather a bold and calculated gamble with potentially large, long-term rewards. Putin is not simply interested in maintaining the status quo; he wants to expand Russian influence and strength by capitalizing on the relative apathy of the US and NATO. If successful, Putin may prove to the world that strong and calculated unilateral moves can serve an effective foreign policy strategy, even if they make Russia lonely.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.