Last month I participated in a foreign affairs simulation hosted at the US Air Force Academy, co-sponsored by the US Department of Defense, the Mellon Foundation and Dickinson College. Students of international affairs from a variety of universities were teamed up with cadets and midshipmen from US Military Academies to fill the roles of the Augmented Deputies Committee, a body of senior government officials from all branches of government that advises the National Security Council and the President on issues of national security. A group of highly accomplished academics and government officials with decades of public service experience took on the task of designing and running the simulation as realistically as possible.

This article is an abridged first-person account of the exercise we conducted over three days in the beginning of March; during it I filled the role of Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Department. Some details have been modified for the sake of brevity. Alongside a nightmarish scenario, I also try to describe the work atmosphere of the Executive Branch as it was simulated for us. We had to cope with miscommunication, unreliable information and a lack of group cohesion, just as a young presidential administration would five years from now. Through the simulation I discovered that there is always a human element to governing, and hope to provide a glimpse of that too.

[hr]The date is 31 January 2021, and the newly elected president has been in the White House for ten days. The incumbent elected in 2016 had lost re-election to a centrist politician in 2020. The National Security Staff and Cabinet had barely moved into their offices when the third gut-wrenching intelligence report hit the room, courtesy of the Deputy Director for National Intelligence: “The Israelis are beginning preliminary preparations for a unilateral airstrike.”

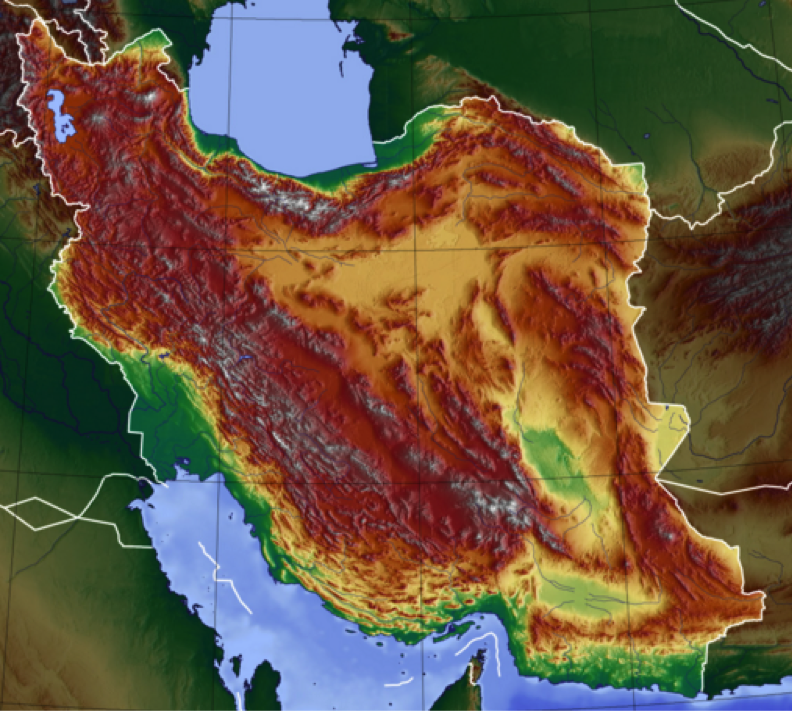

At this point, we knew the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, had heard the same reports that we had—Iran had secretly set up an undisclosed uranium enrichment facility. Israel considers any Iranian attempt to develop fissile nuclear material to be an existential threat, and thus would not hesitate to remove the facility by any means necessary.

“How long do we have?” asked a State Department officer.

“Depends what they’re after. They’ll take their time selecting targets carefully. Tel Aviv will only want to do this one time if they really go through with it.”

Reports began floating in that the Iranians were hiding 1,000 centrifuges from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). (Centrifuges are big, rapidly spinning containers used to separate Uranium-235[1] from Uranium-238.) If we had not prevented Iran’s development of the bomb through diplomatic means back in 2015, Israel would have had no problem acting alone to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program. Yet with these new reports, the tenuous peace appears to have been broken.

We also heard that a senior fellow from the Brookings Institution, an American citizen who was visiting Tehran on an academic trip, was detained by Iranian law enforcement last night for unknown reasons. So in addition to the usual crew from the intelligence community and the Departments of Defense and State, the White House called in Homeland Security, the Justice Department, Energy Department and my beloved Treasury to form the Augmented Deputies Committee.

“So what should we be doing?” asked my Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Intelligence and Analysis (the title barely fits on her business card). She had been chugging bottles of Robitussin since 7AM to hide her bronchitis.

“Well, if the Attorney General wasn’t in the room, I’d be buying oil futures before this news hits the markets,” I joked. “Any news that stokes fears of Middle East instability will give oil a ten dollar boost these days, so any sign that Iran has belligerent intentions will send it off the charts.

“So what do we do?”

“Well, nothing right now. This is still State and Intel’s ballgame, so I think I might go visit State. Think you could find a copy of the SDN list? We should go over it and see if any obvious names are missing. Let’s have some names ready for the White House to sanction at will.”

“But sanctions don’t work. We’ve got reams of reports telling us that. It’s a waste of our time.”

“Of course they don’t work. But it sounds good to the American people, and I think the man in the Oval would like to make it to February before his approval rating drops below 60%. Let’s feed some new SDN’s to the media so they don’t eat this administration alive.”

The SDN list, or Specially Designated Nationals list, has the names of every person that the US has implemented special sanctions against. It’s composed of mostly Iranians, Russians, North Koreans, a few African dictators and a bunch of terrorists. If we could add some Iranian scientists or clerics to the list, that could dampen the public outcry when this inevitably leaks—buying us time to find a real solution. But I wasn’t visiting the State Department office to explain all that. The Deputy Secretary of State was trying to get the Israeli ambassador on the phone when I walked in.

“Hey Bren, got a sec? Need to see you and the American ambassador to the UN.”

He hung up the phone in disgust. “The Israeli ambassador is participating in a Latke-Hamantash debate at Georgetown during an international crisis. Unbelievable.”

“Yeah, well, you don’t need her. We can make a public move to delay Tel Aviv by asking for an IAEA inspection team.”

He stopped to think about it, but I could tell he understood the reasoning. If Israeli jets bombed UN inspectors on a peacekeeping mission, the entire world would eviscerate them. They couldn’t afford to bomb Iran unilaterally while inspectors were in the country. “We still don’t know where to send them,” he countered.

“We don’t have to announce a location right now. We just have to make a statement from the White House and ensure it gets voted on in the Security Council later today. It won’t be hard to get the Russians and Chinese on board if they know that the Israelis are already strapping bombs on their planes. It buys us time, and we can use that to gather more information. It also saves us from having to implement unilateral sanctions if this were to get leaked. We can keep the Israelis fenced in and take control of the news cycle on this one.”

He nodded in agreement. “Let’s run this by the Deputy NSA.”

[hr]Aside from the missing Brookings Institution fellow, we felt like we had most things under control for a few hours. Russia, China, Germany, France and the UK were all on board with the plan to send international inspectors to Iran. But as we were walking into our third plenary meeting, nearly everything spun out of control.

“Khameini is dead? Did I hear that right?”

Yes you did, Mr. Assistant Secretary of Something Obscure from the Department of Energy.

A White House official was enjoying an I-told-you-so moment. “He’s been out of contact for days and we have good intel that he went into the hospital over a week ago! He’s probably been dead for a while now, and we have nothing in place to deal with this!”

Worse, the Iranian public didn’t know yet, and it was unclear if the regime wanted to announce his passing. Without an Ayatollah, the Iranian government is essentially leaderless. We had asked the Iranians to accept an IAEA mission to look for undocumented centrifuges, but the mission approval relies on the Ayatollah’s consent.

The presence of IAEA inspectors was meant to be our insurance policy against an Israeli strike on Iran, and that was no longer possible. On top of that, the Israelis would probably love to hit a dysfunctional Iranian government.

“New intel came in,” said the White House’s Deputy Chief of Staff. “The IRGC are mobilizing and spreading across the country. Looks like a possible coup.”

The Ayatollah of Iran is perhaps one of the most hated Middle Eastern political figures in the West. Having him gone would be a dream come true on literally any other day. But having the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) ascend to create a theocratic military dictatorship would be worse. With no obvious solution in sight, we spent most of a few hours bickering among ourselves and hoping for new intelligence that might provide a pathway out of this mess. But it never came.

“Guys, we don’t have any other quick fixes to slow down the Israelis, and there’s only one way we get the IAEA into the country. We need an Ayatollah.”

[hr]Personal experience has taught me that in government, most of the scenarios you plan for never actually occur, and the ones that do become real are never precisely what you imagined. Eventually we all agreed to break the news of the Ayatollah’s death in order to speed up the process of getting a new leader selected. But we had to accomplish that without appearing to be the leakers: if we broke news of his death, that would be like Kim Jong Un announcing the death of a sitting US President. Ayatollah Khameini is of ethnic Azerbaijani descent, so we decided that if the news had not broken by the next morning, it would be leaked to Azerbaijani media disguised as a tipoff from a distant relative.

The next morning, Iranian authorities had announced his death and our hours of designing a nearly foolproof leak were for naught. We decided to prioritize working out a diplomatic resolution with what was left of the civilian government in Tehran before making any regional moves. Threat levels were raised, travel advisories were issued and our sincere condolences were shared with the Brookings researcher’s family and colleagues, as a video of his beheading had surfaced overnight. We nervously watched IRGC units mobilize across the country, unsure if they were cementing a coup or deploying to prevent political unrest in the wake of the Ayatollah’s passing. We began contemplating military and economic options that could be useful for responding to any of the possible outcomes in Iran.

Ultimately, we enacted a policy of “strategic patience” — observing and doing nothing, waiting for an opportunity to act — while we tried to make sense of a new Iran. This was just the beginning of a scenario that would have implications for many years beyond 2021. And we had only dealt with the first two days of it.

[1] U-235 is an atom of uranium with three less neutrons than normal. Therefore it is less stable and useful for anyone trying to build an atomic bomb. Under the Iran Deal signed in 2015, the Iranians are supposed to have only a certain number of centrifuges and let the IAEA monitor them to ensure that they don’t enrich a mass of uranium above 3.67% U-235.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.