For duck you say “antis.” Quack!

My earliest memories were spent with my grandma, or my Močiutė. For several years she lived in a vacant room in our basement after emigrating from Lithuania, and that made her my babysitter during my most formative adolescent years. Afternoons were spent feeding ducks in the park while she’d try to teach me Lithuanian words in broken English.

Goodbye is “ate!” Bye bye ducks!

We spent enough time together that at three years old, I actually responded to Lithuanian commands as much as English ones.

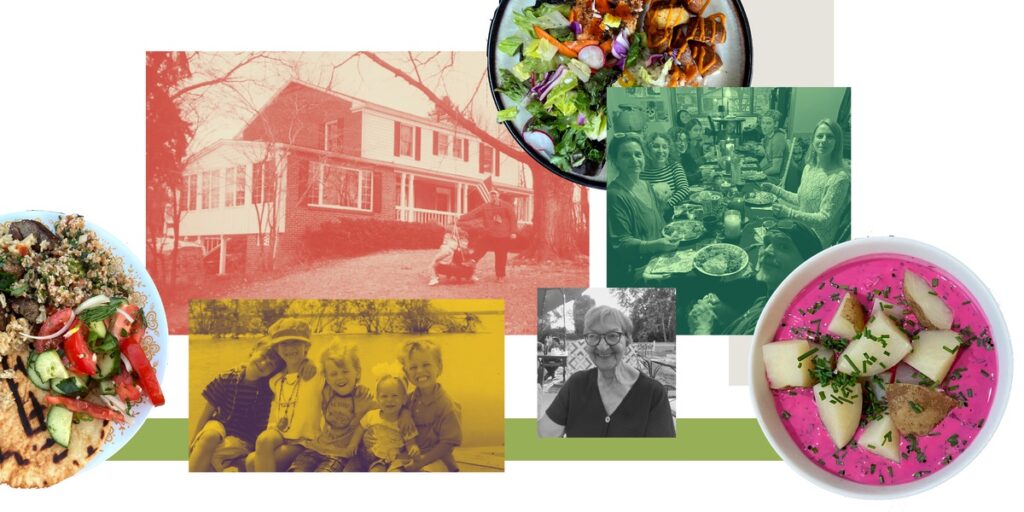

Throughout my entire life, I’ve lived in a multicultural household. My very upbringing was born out of a cross-cultural exchange. My mother — a Peace Corps volunteer — met my father while serving as an English teacher in Vilnius. Because of this, Lithuanian heritage was woven into the fabric of our home. Every year we celebrated Kūčios, or Lithuanian Christmas Eve, where dinner was a heaping spread of herring, beet salad, poppy seed milk and sauerkraut. Grandma was to be called Močiutė and Dad was Tete. Our walls were decorated with memorabilia like ornate sashes and handmade ceramics that my mom collected during her time in Vilnius.

As such, my pride in my father’s country was unwavering. Most kids at school didn’t know what Lithuania was, but that was the only country I could point out on a map.

My other side of the family is more traditional American, mostly Italian and Hungarian. My maternal grandma swears by her Italian heritage, with dozens of cousins and a tendency to pray to Saint Anthony every time she loses her iPad. Even though our Italian family arrived at Ellis Island three generations ago, her affinity for heavy lasagna recipes and gold jewelry would have you convinced her last name is Soprano (DNA evidence actually proved that we have no Italian blood in our family — they emigrated from Albania).

“It’s from this side of the family that you get those dark circles under your eyes!” she’d always say. But there was certainly truth to her European roots, and it influenced the way that she and my mother raised me. Standing around our table to make a gnocchi recipe passed down from my great grandmother or making Hungarian meat patties with my mom after school were some of my favorite memories as a kid.

Family had a loose definition. While my mom had five biological children, we later adopted three siblings from another family. My mom previously fostered a few kids from abusive or neglected backgrounds, so she was familiar with the system and its flaws. A year later, we had another addition to the family when my godsister — who lived in Mexico City — moved in with us because her mom wanted an American education for her but she was the only person in her family with American citizenship. Her only connections were in Akron, where her grandma and uncle lived. This meant that although she lived with us, her grandma would send down big batches of tamales, mole — and during New Year’s — some pozole. By middle school I was well acquainted with the peppery taste of cilantro, the tartness of fresh lime and the creamy, oily flavors that thick Mexican stews provide.

Beyond my family, I also just grew up around a lot of people. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized how bizarre my upbringing was. While I lived in suburban northeast Ohio, my family was anything but nuclear. Our home had a revolving door for family, friends, and at times, strangers. After my Močiutė moved out, the vacant room was quickly occupied by some friends from the Peace Corps — a newly-wed Hungarian couple — after they won the green card lottery. I’m told that I would put on a show for them during dinner time in my high chair (dumping a bowl of spaghetti on my head was apparently an audience favorite). They liked to make us traditional Hungarian dishes, especially goulash. The smokiness of paprika — married with the sweetness of onions and carrots and blended with the nutty, sharp flavor of caraway seeds — made for a homey stew that could even warm your soul. It’s a recipe I still use today on a cold winter night.

Our broad definition of family opened our doors to anyone who needed it. For a year we had a Lithuanian family friend staying at our house while she fled an abusive marriage. They occupied the same room that my half-sister lived in two years prior, where she raised her newborn baby after quickly emigrating to the States following an abrupt teen pregnancy. Sometimes, we even housed complete strangers. We had five exchange students from France, two from Ireland, and even several members of the American Boychoir for a couple weeks. At any given time, there was someone, somewhere, speaking in another language. The long, stretched sounds of my dad’s Lithuanian made his words feel like a viscous fondue in my ears, while my godsister’s Spanish had a more melodic cadence that bounced quickly off the tongue. It was as if my house was a symphony of sounds, accents and dialects.

But a porous family certainly doesn’t come without its problems. When I was 13 years old, my parents divorced and the dynamic of my household was rattled. My mom was unemployed and raising nine children by herself, while my dad was growing increasingly distant. Kūčios was now celebrated in my dad’s one bedroom apartment and without my mom, which felt much more hollow than the boisterous family event it used to be. Similarly, my dad’s absence from our house meant that the linguistic and cultural energy was also absent. The air of our home felt still, the atmosphere was dry and the remnants of my previous life were quickly disappearing. My world was crudely cut in two: one American, Mexican, Italian and Hungarian — and distinctly separate was the Lithuanian one.

I’d like to think that this began to change in 2017. My mom reconnected with her fiancee from 22 years earlier — a Puerto Rican chef with a thick Bronx accent and an upbringing shaped by the Caribbean. He had a family of his own, but of course, that was nothing new to us. I gained another (step) sister, a nephew and roughly a dozen cousins. My mother’s remarriage kick-started a unifying period for our home. The kitchen regained a familiar sound of metal clanking and its aromas saturated the walls again, but this time with pungent West Indian curries, stewed goat and a sofrito seasoning of cilantro, garlic, onion and sweet aji peppers.

At the same time, I began to reconnect with my dad a lot more. By high school I was able to process his idiosyncrasies with a much more nuanced perspective. His Soviet upbringing was responsible for a lot of his behaviors that put strain on his marriage, whether it was excessive alcohol consumption or emotional unavailability.

But in talking with him, I began to appreciate some of the ways in which he raised me. In third grade my MP3 player was full of Aerosmith, Kiss and AC/DC, but it wasn’t because I was an avid punk-rock fan. It’s because it’s all that he blasted in his ‘99 Ford Taurus. I now realized why he loved the music so much: it was banned in the Soviet Union. It’s the same reason why he loved Catcher in the Rye, Animal Farm and Robinson Crusoe — it was literature that could only be read by mischievous teenagers eager to defy the regime through black markets. It was these experiences that led him to prioritize education in his children and ensure that they were avid readers and critical thinkers (and punk rock fans).

While moving boxes into his new apartment, I stumbled upon a trove of photos and posters that he had collected as a college student. The papers, delicate to the touch and yellowed from age, were from the Lithuanian independence movement. They read slogans like “Red Army Go Home!” and “UN Abolish Colonialism,” which pushed to repudiate the 1940 annexation by the Soviet Union. I’d later find out that he actually protested against Soviet aggression in Vilnius in 1991, which quickly turned violent as Soviet tanks bulldozed the city and fired shots into the crowd, killing 14 and injuring over 700. It was a testament to the strength of Lithuanian statehood, and would later become one of the most well-known confrontations between the Soviet Union and Lithuania. He was there.

By the time I entered college, I had discovered my passion for the democratic cause. I pursued international relations because this was a vehicle for me to support this through policy, research, advocacy and scholarship. My courses in international law, geopolitics and political risk analysis help me understand important global events like democratic backsliding and conflict because they have direct effects on my family and friends living in places like Lithuania, Hungary, France and Germany. When I study human rights and politics in Europe, I am thinking about my cousins and old foreign exchange students that are affected by radical policy changes or growing authoritarianism. With the hopes of later becoming a diplomat, I wanted to get involved as much as possible. I joined a research lab on campus to study civil war, I started writing about international issues through campus publications and I spent my summers interning with Congress, think tanks and the foreign service. I threw myself into the world of diplomacy in an effort to become a true global citizen.

When I come home, this feeling is beaming from my home. Now Kūčios is no longer the traditional Lithuanian holiday that it was, and that’s okay. My Močiutė brings the usual spread of fish and eggs, but because of my stepdad, the spread now includes warm, flaky Jamaican beef patties and sizzling skirt steak with vibrant chimichurri. We sing Lithuanian songs before blasting upbeat Cuban rumba. The walls struggle to fit the 30 of us that come from all around the world, and the melody of accents and languages saturates the air again.

I used to think that I only became passionate about international affairs in the last four years, but now I would argue that this is who I’ve always wanted to be: a global citizen, a diplomat, a researcher, a teacher, and above all, an explorer. And I have my family to thank for that.