On July 6, 2017, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres announced Cyprus’ 11th failed peace talk to reunify the north and south in 43 years. A divided nation since 1974, Cyprus is located in the eastern Mediterranean at a strategic commercial and cultural intersection between Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. As a familiar stalemate to the Cypriot population, the reunification conflict is its own sociopolitical battle between two proud Cypriot peoples as well as a proxy for broader Greek-Turkish tensions.

Last April, I had the opportunity to travel to Cyprus while studying abroad in Europe. During my visit, it was evident that Cyprus is home to conflicting national and regional prides. Greek and Turkish influences have a stronghold on the island and on their respective conflicts. Traces of historical empires like the Assyrian and Egyptian remain, and intricate mosaics and ionic columns still decorate the coastlines where Alexander the Great once walked.

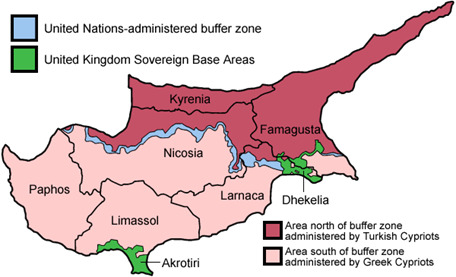

I learned that the Republic of Cyprus, carved out by Greek Cypriots in the south, claims membership to the European Union and resembles Greece in language, currency, and culture. The population in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus uses the Turkish lira and largely practices Islam. The TRNC remains unrecognized by any country besides Turkey, and both the Greek and Turkish sides maintain close military ties with their respective mainland sponsors. Because of these differences, I truly felt as if I were visiting two separate countries, as I explored coastlines, cities and ruins.

As a tourist, I frequently crossed Cyprus’ UN buffer zone dubbed “the green line” that bifurcates the country and capital city of Nicosia. In some ways, the wall was eerily mundane. UN Peacekeepers ordered Doritos from a convenience store on the Turkish Cypriot border before crossing into the buffer zone for duty. Tourists, indifferent to the conflict, joked that beer was cheaper on the Turkish side and that the Greek side had better food. Cobblestone streets, marketplaces, and restaurants bustling with people on either side of the line almost seemed to ignore it. At one restaurant, I was close enough to reach out and touch the wall.

In other ways, though, the buffer zone did feel like the symbol of ongoing conflict and social division. In the less lively parts of Nicosia, the wall was riddled with graffiti, sandbags and rusted barrels. Streets that dead-ended at the wall echoed with crime. My Greek Cypriot host, Athena, scoffed that she would never set foot near it or speak with any Turkish Cypriot who resided beyond it. Once, when I crossed the border, handing over my passport to Greek Cypriot authorities, then to the Turkish Cypriot ones, I noticed how militarized both stations were, with cameras installed everywhere and officers carrying massive guns, scrutinizing me.

Cyprus has a complex identity, having been a trading center since before 3000 B.C.E and occupied by various kingdoms, with particular strongholds from the Greeks and Ottomans. Cyprus’s contemporary identity was shaped in 1914, when Britain annexed the island strategically against its adversary, Turkey. Greek Cypriots anticipated that Britain would unite them with Greece, to the resentment of the island’s Turkish counterparts. The Greek side’s campaign for enosis (Greek for “unification”) and Turkish Cypriot resistance led to alternating waves of petitions and reactionary riots between the two groups for decades. In 1974, Turkish forces arrived at the northern port of Kyrenia to overthrow the coup and succeeded in establishing a bridgehead around Kyrenia, which linked to the Turkish sector of Nicosia.

Turkey’s invasion solidified the island’s political and cultural separation. At that time, 140,000 Greek Cypriots fled to the south and 40,000 Turkish Cypriots in the south abandoned their livelihoods and moved north. Aggression and failed peace talks continued throughout the 1980s and 90s, and by 2002, the European Union offered Cyprus membership on the condition that the country would reunify. When that failed, only Greek Cyprus was admitted in May 2004.

Cypriots themselves often joke that any difficult and prolonged situation in the world “has become like the Cyprus problem!”[1] Clearly, attempts at a Cyprus resolution have resisted traditional methods of diplomacy, as disagreements during negotiations prompt both sides to retreat back to their positions. This is due, at least in part, to Cyprus’s two-pronged challenge: local identity crisis and global role ambiguity. Locally, Cyprus is geographically concentrated with deep-rooted cultural and national prides, spanning a history of thousands of years. Similar to cases like Northern Ireland and Sri Lanka, Cyprus harbors divided definitions of identity, where each side finds the opposing side a direct threat to the identity they believe to be true. Unrecognized Turkish Cypriots have faced an inferiority complex to the rest of the world while enjoying state and international institutional benefits. The Greek Cypriots are still embittered by Turkey’s divisive invasion as well as failed efforts to have a more unifying framework with Greece.

Undeniably, though, Cyprus’ two identities are irreversibly enmeshed in the governments, economies, and cultures of Greece and Turkey. From Turkey’s political unrest to Greece’s economic recovery, Cyprus has competing interests at play from major world powers and their allies, and this contributes greatly to continued peace talk failures.

Ultimately, Cyprus must reach a plan in which both sides can compromise as a nation and remove historical tensions from Greece and Turkey. Overcoming the challenge to peace requires recognition of mutual interests shared by the two communities. Turkish Cypriots must acknowledge that Cyprus has long abandoned its intention for enosis with Greece, and this was further confirmed by the collapse of Greece’s banking system and subsequent bailout in 2013. At the same time, though, the Greek Cypriot side must accept a solution that allows for Turkish Cypriot recognition in the world.

Perhaps the most symbolic concession for mutual understanding would be the removal of the buffer zone between the two populations. During my trip, one of the only times I was able to envision this possibility was during my visit to the Home For Cooperation (H4C), a nonprofit organization inside the zone that provides Greek and Turkish Cypriots opportunities to intermingle. The H4C offers language courses in Turkish and Greek and hosts dances and other cultural functions.

While inside the group’s building, I could still hear the Islamic call to prayer crackling on the intercom on one side and Greek Orthodox church bells on the other. Both sites were probably less than a mile away. While I was speaking with the director, I could hear both worship sounds trickling through the buffer zone into my ears, competing, bickering, and mourning.

My hope is that Cyprus can soon overcome its failed conventional peace talk framework and find a way for its populations to coexist peacefully. Through historical respect, cultural awareness, and careful political planning, it is not too difficult to imagine a future with Turkish and Greek Cypriots dancing together without garrisons and guns and the Orthodox church bells and Islamic calls to prayer sounding in proud unison.

[1] Michael, Michális S. “The Cyprus Peace Talks: A Critical Appraisal.” Journal of Peace Research Vol. 44 Issue 5, pages 587-604. 1 September 2007. Print.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.