In the four months since the coalition of Gulf States—Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates—cut their diplomatic ties with Qatar and initiated a land, air, and sea blockade, little movement towards a resolution has been made. The conflict has drawn international attention as interstate relations in the region have consequently changed. US Secretary Rex Tillerson’s involvement signals the global concern with the situation and the potential destabilizing force these shifting relations hold.

The current crisis dates back to June 5, when the coalition states announced the blockade, citing accusations of Qatar’s financing of terrorism and its ties with Saudi Arabia’s rival Iran. The blockade has interrupted business and trade connections between Qatar and its neighbors. These economic linkages are integral to the Qatari economy, as Qatar imports approximately 40 percent of its food overland through Saudi Arabia and depends on the UAE as a major destination for its oil exports.

Despite potential ramifications for its economy, Qatar has refused to accede to the coalition’s demands. This likely stems from a desire to maintain its autonomy: Qatar is a small country that has faced Saudi Arabia’s “dominating, conservative influence” since its independence from Britain. The ability to not acquiesce in spite of the potential economic consequences can be partly attributed to Qatar’s vast oil reserves, which have allowed it to amass a sovereign wealth fund of an estimated $335 billion. Still, the potential for economic hardship has forced Qatar to adjust its relationships with other countries in the Middle East.

Still, economic concern is present, which has resulted in adjustments to Qatar’s relationships with other countries in the Middle East.

Qatar’s relationship with Iran is a principal cause of Saudi Arabia’s frustration, having maintained closer ties with Iran over the years as a product of their shared natural gas resources. The coalition states’ list of demands included suspending relations with Tehran, but Qatar not only refused to acquiesce to this condition, but it also moved to strengthen relations with Iran.

In late August, Qatar resumed full diplomatic relations with Iran by returning its ambassador to Tehran following a period of 20 months during which Qatar suspended ties in response to attacks on Saudi diplomatic facilities in Iran. Continuous support from Iran in the wake of the blockade accompanied the restoration of ties. Since June 5, Iran has opened its airspace for Qatari airplanes and has provided sea shipments of fresh food. These steps have enabled Qatar to maintain its challenging stance despite facing economic challenges and indicate a bold defiance of Saudi Arabia’s demands and attempts to dictate Qatar’s foreign relations.

Qatar’s alignment with Iran holds global consequences, particularly as the US considers its stance in the conflict. The US must balance its relations and protect its interests in the region. In doing so, it must consider the consequences of siding with each party of the conflict. To align with Saudi Arabia would mean the US would have to leave its base in Qatar, its largest in the Middle East. On the other hand, siding with Qatar as it moves closer to Iran would contradict professed American foreign policy.

Qatar has also turned to Turkey in response to the crisis it faces with its closer neighbors. Turkey quickly sent planes of food to Qatar after the country faced potential food shortages due to Saudi Arabia’s closure of Qatar’s only land border. Qatar has also strengthened its military ties with Turkey. In August, troops from Turkish and Qatar navies undertook a joint exercise, Iron Shield, with the goal of “exchanging information, training senior military officials and improving coordination between the two forces to boost security.” As a more tangible demonstration of their military relationship, Turkey fast-tracked legislation and approved Qatari troops’ deployment to Turkey in the days following the blockade announcement.

Turkey has made its ties with Qatar clear to the coalition states, refusing their requests to shut down its military base in Qatar. Instead, Turkey intends to increase troop numbers to 3,000 in keeping with their agreement and plans to keep a brigade in the country. These are clear signals that the blockade has served to strengthen Qatar’s alignment with Turkey. And like the difficulties posed by Qatar’s relations with Iran, Qatar’s relationship with Turkey poses a similar challenge for the United States, in light of current tensions between the Trump administration and Turkey.

Though largely a cause for concern in the region, the crisis has also proved to be an opportunity for one state. Since the crisis, Kuwait has worked on negotiating between all parties to find a solution. As the typical regional powers are caught up in the conflict, Kuwait has taken this unique opportunity to establish itself as a leader in resolving the conflict.

Kuwait hopes to successfully restore relations between all parties and normalize ties in the Gulf, warning that the persistence of conflict could result in the collapse of the Gulf Cooperation Council and threats to the security of all countries in the Gulf. In mediating this crisis, Kuwait hopes to avoid these consequences but also fulfill its own interests: sustaining relations with Qatar and the states involved in the blockade and promoting its reputation regionally and globally as a mediator and stabilizing force in the region. It remains to be seen if Kuwait can succeed in bringing together these parties and resolving this dispute.

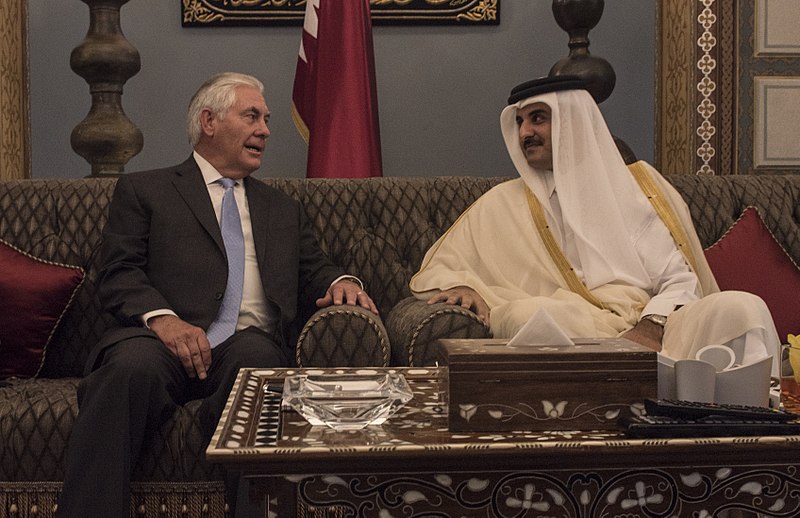

The US has also undertaken a mediating role. Tillerson has been active in the region in the months following the breakout of conflict. His first attempts came in July, partaking in shuttle diplomacy as he met with leaders in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait. Though he signed a memorandum of understanding regarding efforts to fight terrorism with Qatar, the trip yielded little more as the four states insisted that the memorandum was not sufficient. In October, Tillerson returned to the region, emphasizing the importance of finding the resolution as he called for “the GCC to continue to pursue unity.” Again, these efforts proved futile as Tillerson noted Saudi Arabia’s resistance to enter discussions with Qatar.

Changing relations in the Middle East hold consequences across the global community. In a broad sense, the conflict perpetuates instability in a region plagued by insecurity. The Gulf states are typically seen as the region’s pillars of stability. This new rift adds yet another layer of uncertainty to the Middle East puzzle. The US must also be careful in determining its position within the conflict. While Tillerson has maintained a neutral position, he has also expressed growing frustration with the lack of compromise; the world will be watching closely as the US navigates this conflict which seemingly has no near end in sight.