Xiaomi is outselling Apple in the Chinese smartphone market, and recently announced its plans to expand globally. You may be asking: “Xiao-who?” Well, here is an introduction to the hottest tech company in China, their blueprint for expansion, and what this means for China’s growing “soft power” – a construct that emphasizes a state’s economic and cultural influence.

Ascent to Stardom

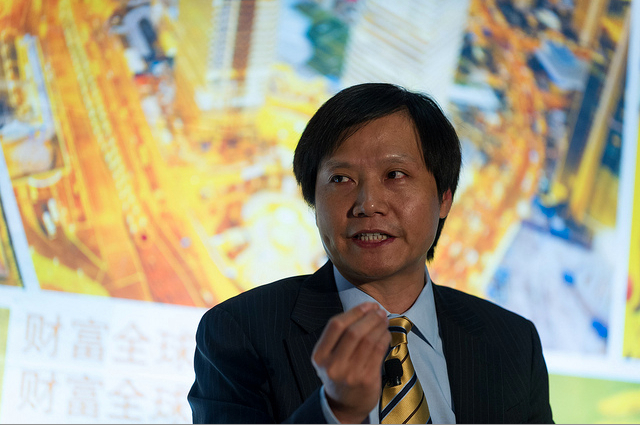

Xiaomi Inc. is an Internet service and consumer electronics company founded in April 2010 by Steve Job’s Asian twin, Lei Jun (see photo). Selling high-end smartphones at near production costs, Xiaomi has challenged Asia’s top smartphone providers in the Chinese, Taiwanese, and Hong Kong markets. In the second quarter of 2013, Xiaomi became the fifth-largest supplier of handsets in Mainland China. In August, Lei poached top Google executive Hugo Barra to orchestrate Xiaomi’s global expansion. And shortly thereafter, a “flash sale” of 100,000 Hongmi-model smartphones ($135 compared to the $750+ iPhone) sold out in 90 seconds. In October, Xiaomi sold 100,000 of the luxury Mi3-model smartphones ($327 for 16GB or $410 for 32GB) in 83 seconds. Less than four years after incorporation, Xiaomi has gained Apple-like popularity and a market valuation at $10 billion (equal to Lenovo or double that of Blackberry). Xiaomi executives project smartphone sales in the neighborhood of 20 million units by year’s end.

International Expansion

But they aren’t satisfied. At a recent media event in Taiwan, Lei and Barra announced their expansion into the Southeast Asian market, specifically Singapore and Malaysia. Why? Singapore and Malaysia have the necessary technological (network coverage) and regulatory (welcoming governmental and legal institutions) infrastructure for Xiaomi’s entry. Further, the people of Singapore and Malaysia are smartphone fanatics. Smartphone penetration in Singapore and Malaysia is at 87% and 80% respectively. Comparatively, the United States is at 60%.

Xiaomi may succeed in its initial expansion—despite entering a saturated market—for four reasons:

- Fandom: “Flash sales,” and the social media blitzkrieg surrounding these events, have generated frenzy among middle-class shoppers eager for the newest smartphone. Further, Xiaomi allows its customers to actively shape its software platform. Miui, a spinoff of Google Android software, is updated nearly every week based on the suggestions of its 5.1 million members. Client-customer collaboration has boosted Xiaomi’s popularity in China and promises to do the same in Southeast Asia.

- Increased competition: Samsung has run a near monopoly in the Southeast Asian smartphone market. But three Asian companies, Huawei, Lenovo and LG, are challenging its dominance and eating away at its market share each successive quarter. Xiaomi could benefit from an increasingly diverse market.

- Subsidies: Singaporean and Malaysian telecom operators offer smartphone subsidies. Thus, Xiaomi phones could be free with the purchase of a contract—an enticing offer for those who disheartened by the larger sticker price of a Samsung or Apple handset.

- Apps: Singaporeans and Malaysians love apps. In fact, they score highly (Singapore at number one) in the World Mobile Readiness Index, a metric that calculates a population’s willingness to pay for mobile apps. Singaporeans’ and Malaysians’ willingness to pay for apps perfectly accommodates Xiaomi’s business model. Xiaomi has razor-thin profits on smartphones (compared to a company like Apple that has a 55% profit margin on the iPhone) and therefore relies on apps and accessories to generate profit.

Litmus Test

Xiaomi’s success in Singapore and Malaysia will be indicative of its potential success outside the Chinese mainland. Xiaomi has thrived in the Chinese market where Apple holds less than 5% market share and Google Play (Google’s “App Store”) is not officially available. How Xiaomi competes in areas where Apple and Google have a stronger grip will be telling. If unsuccessful, Xiaomi will likely retreat to China. If successful, look for Lei and Barra to deepen expansion in Southeast Asia, particularly in the Philippines—a country with a higher Mobile Readiness score than Malaysia and Hong Kong yet with only 15% smartphone penetration. The Filipino market would be wide open to an injection of Xiaomi products.

China’s difficulty in accumulating soft power has been well documented. However, much to the chagrin of some Americans, China’s soft power, particularly its global economic influence, is on the rise. A burgeoning tech market has begun to stimulate international growth for a number of Chinese companies (think Lenovo, Baidu, and Haier). Xiaomi’s success in Southeast Asia could demonstrate or precipitate greater success of Chinese companies in foreign markets. As a result, Chinese communication technology may attain the “cool factor” of Apple or Samsung products—which are widely regarded as fashionable and reliable. In short, Xiaomi may trigger consumers of Chinese tech products around the world to begin prizing the “Made in China” tag rather than associating it with mediocrity. And such a rise in economic influence is a necessary characteristic of any great power.