In 1979, Deng Xiaoping, former leader of the People’s Republic of China, implemented a one-child policy in China which ordained that each family could have only one offspring. Fear of overpopulation and another famine occurring soon after the devastating Great Chinese Famine of 1962 were the primary drivers behind the enactment of this law. Deng believed that by limiting the number of children born in China, the population as a whole would gain greater access to basic necessities and better opportunities for economic success. China enforced this policy by requiring intrauterine devices after the birth of a child and imposing punishments such as forced abortions and sterilization for a second pregancy. China abolished its one-child policy in 2015.

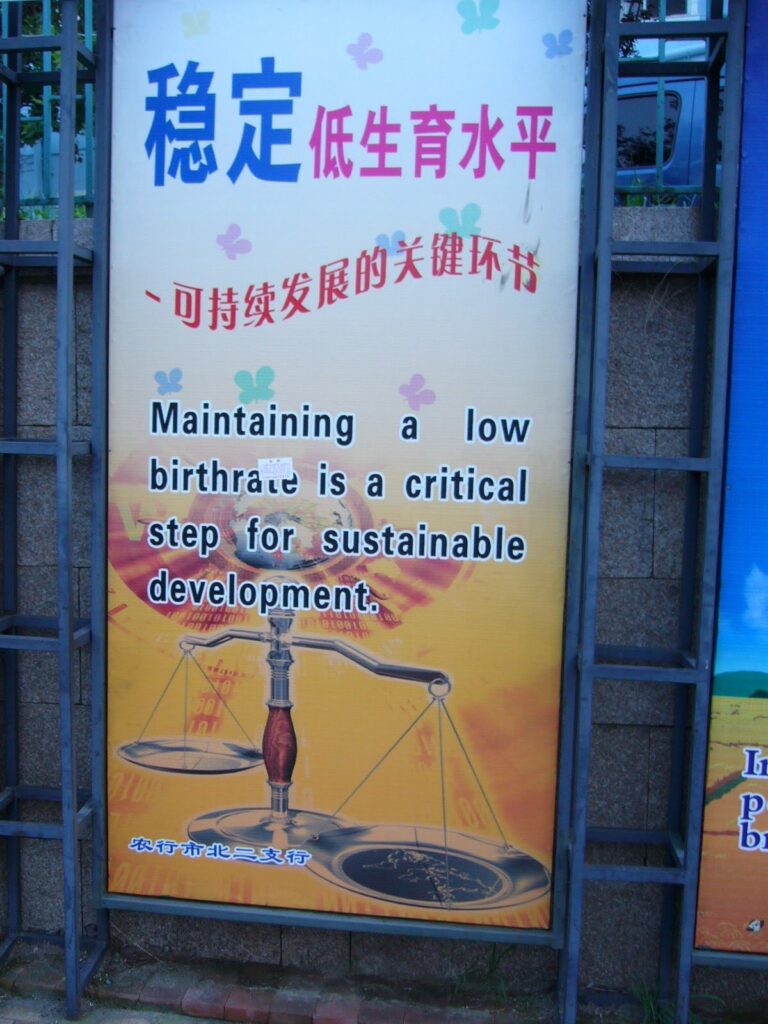

Use of Propaganda

The Chinese government inundated its people with slogans touting the benefits of having one child. These messages were found everywhere, from billboards to murals to images printed on decks of cards. The Chinese shibboleth “If you want to become rich quickly, have fewer children” was ubiquitous.

Those raised during the era of China’s one child policy still bear psychological scars. The victims include more than the mothers who underwent forced abortions or the doctors who performed them. In her September 2019 TED Talk, Nanfu Wang spoke with great emotion about her experience growing up in the time period, saying “I remember feeling a sense of shame because I had a younger brother.” The government propaganda filled the Chinese with such a sense of national duty that many were left with overwhelming guilt if they did not abide.

Abandoned Children

Perhaps the worst consequence of China’s strict one-child policy is that violators sometimes abandoned their children. Some of these abandoned children were left at shelters, while others were tragically abandoned in dumpsters or sewage pipes. The children deserted were most frequently female and sick or disabled because these children were considered less desirable in Chinese society.

Recognizing the abandonment crisis, in 2011, China began building “baby hatches,” or safe places for parents to drop off unwanted children. Many opposed the safety drops because they believed it encouraged abandonment, but experts argued that parents were going to abandon their children under any circumstance. 2016 estimates place the number of orphans in China at 460,000. Tragically, most of these children may never find a home, since children over the age of fourteen are ineligible for international adoption.

China’s Missing Women

The government creates one sole exception to the one-child policy. If a couple had a daughter, they could try again for a son who was more likely to work and bring economic success to the family. However, complications arose when the second pregnancy was also female. These pregnancies often either went unreported or were terminated in sex-selective abortions. This strong preference towards male children led to a significant gender imbalance in China’s population, which has created what is known as China’s “missing women” issue. As a result of this imbalance, studies indicate that by 2020 nearly 24 million Chinese men will experience great difficulty finding wives due to a lack of suitably aged women. Sociologists predict the imbalance will lead to intergenerational marriages, where younger men marry older women. However, such marriages pose further complications for couples as the older women may be beyond child bearing age. Additionally, there is an unknown number of women (“missing women”) who are excluded from receiving state welfare benefits and lack many rights afforded to Chinese citizens because their families failed to document their births by registering them with the government.

The 4-2-1 Problem

Most recently China’s growing concern is the “4-2-1” problem. This 4-2-1 dilemma is the generational burden borne by an aging population of men who are “only children.” It is called the 4-2-1 problem because it explains the dynamic of an adult male who is an “only child”, and who bears the obligation of caring for not only his two aging parents, but also his four aging grandparents. The problem is compounded if these men marry, as they become responsible for their spouse’s parents and grandparents. This financial and social burden only serves to further dissuade couples from having large families themselves.

Was it effective?

At first glance, it may seem that way. China’s birth rate declined while the policy was in effect between the years of 1979 and 2015. However, this decrease cannot be solely attributed to Deng’s law, as the initial decline in birth rates began even before the one-child policy was implemented. One significant factor that contributed to this decline was China’s rapid economic expansion during this time period. Researchers, using data from sources such as the United Nations Population Division and Eurostat, have established a pattern of inverse correlation between fertility and income. As a country develops and experiences an increase in income, its fertility rates decline significantly. This calls into question whether the one-child policy was necessary or whether fertility rates would have continued to independently decline as a natural consequence of China’s growing prosperity.

Will China’s population grow now that there is a two-child limit?

It is very unlikely. Now that families have become accustomed to only having one child, many parents believe that having multiple children would strain their resources. While China previously faced an overpopulation issue, now it faces the opposite: the birth rate is increasingly low. Twenty million children were predicted to be born in 2018, however there were only 15.23 million births that year, two million fewer than the year before.

International implications?

As China’s population ages and fewer young people work to support its economy, China’s position as a global economic leader may weaken. The combination of a shrinking and aging population will lead to less domestic consumption and economic growth, which could have profound consequences for the global market. Currently, people aged over 60 constitute 17.9% of China’s population, a figure which grows yearly. As the number of China’s eligible workers declines, the country will likely suffer, affecting both its position as an economic world power and the global economy as a whole.

The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the Glimpse from the Globe staff, editors or governors.