I have played baseball for over fifteen years, and my family has cheered on the Yankees for over 50. I’m considered the black sheep of my family just for liking the Mets. My father has played all his life and coached my little league team, as his father did the same.

Baseball has always been something that has united our family, provided a sense of togetherness in my community and has helped my father cope with his nostalgia for his childhood. My dad still talks about listening to the radio during the 1972 World Series between the Cincinnati Reds and the Oakland Athletics. He fondly remembers wearing his Reds cap as he cheered for the Big Red Machine in his 1966 Chevy Biscayne on his way to the Carvel ice cream parlor down the road.

To us, baseball isn’t just a game, but rather a way to express our nostalgia for our past. Baseball allows us to indulge in our desire for a more simplistic life in a constantly changing world.

The sport isn’t just significant to me. It’s a large facet of American history and has played a role in crafting American national identity. Baseball started to gain its popularity during the 1800s as the United States was undergoing its own industrial revolution.

As urbanization rapidly increased, the nostalgia for rural America grew. Subsequently, baseball parks began to pop up across American cities, including places like Cleveland, Ohio, and St. Louis, Missouri. These parks served as a platform for Americans to express their roots and rural beginnings.

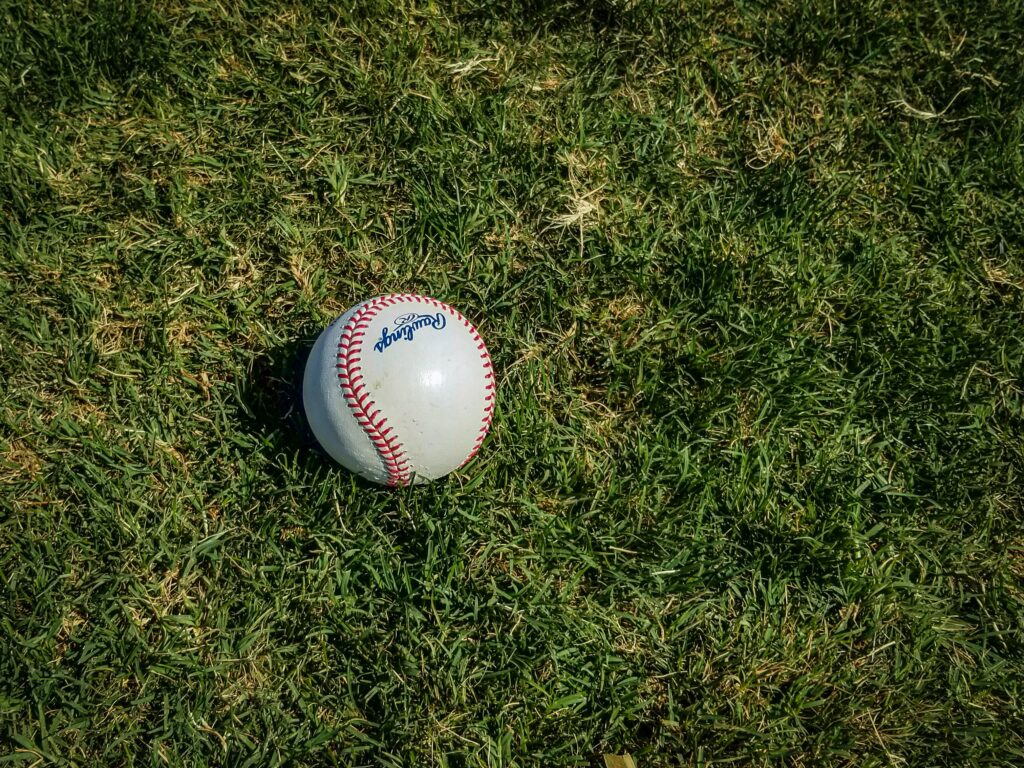

Many Americans view baseball as an expression of their rural origins due to the meticulous design of the game. During industrialization, baseball parks became the only green areas in cities. In the book Take Time for Paradise former Major League Baseball commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti describes the baseball field as a “green expanse, complete and coherent, shimmering and carefully tended.”

The grass of the field represents the vast farmlands of America, which harkens back to Americans’ rural beginnings. Baseball parks are called “parks” because of their grass. In Downtown St. Louis today, the baseball park is still the greenest area in the whole city.

Home plate is the most iconic symbol in baseball and is the centerpiece of the game. In baseball, the goal of the player is to always come home and reunite with the team – the player’s family.

Home is an English word that is almost impossible to translate into other languages. Home is a concept rather than a place. Home provides a sense of inclusiveness, care, comfortability and family. When a player hits a home run, he makes his way slowly around the field and his teammates run to home plate to wait for his exciting arrival at home as the crowd roars cheerfully. In a world where the focus on capitalism and efficiency distracts from the need for home and family, baseball is a reminder of the importance of human connection.

Even the setup of the players in baseball represents the family unit. At home plate, the catcher and the batter are similar to siblings, while the umpire acts as a parental figure.

“This tense family clusters at home, facing the world together, each with separate responsibilities and tasks and perspectives, each with different obligations and instruments,” Giamatti writes.

The family units work together as complements to each other’s skills. Their goal is collective, representing community: to reach home and score runs. This idea is parallel to life on the farm. In rural America, it was critical that each family member had a different skill set in order for the farm to operate properly.

Baseball is timeless. In other sports, the game is almost always timed with a clock; however, baseball has no clock. When baseball first originated, before stadium lights were created, the sport could only be played between the rising and the setting of the sun. If the game did not end, it would continue the next day.

On the farm, a farmer could also only work during the day, and if the work was not completed in a single day, the farmer would pick up the work again the next day. Working on the farm was also not timed, but rather focused on the individual work of each farmer. Baseball is modeled off of agrarian life.

While other sports may have higher viewership today, such as football or basketball, baseball is still widely considered America’s national pastime. Today, baseball is majorly centered in big cities and still provides an escape from the city as it continues to allow Americans to be reminded of their agrarian roots.

Team mascots for minor league baseball connect to our agrarian past too. Examples of this are Shelly from the Modesto Nuts in California, Celery from the Buffalo Bisons, and Mr. Shucks from the Cedar Rapids Kernels.

Furthermore, baseball continues to be consistently dedicated to the origins and authenticity of the game even though big business has become a large part of baseball. Despite the large business involved in baseball, parks still have real green grass. Baseball has always been consistent since the late 1800s. If a player from the 1800s was placed in a baseball game today, the player could probably keep up because the skill set required to play the game transcends time.

While the design of the game and its connection to the heart of America may often be overlooked, the relationship between sports and the American dream is not. The ability for players to be rewarded for their skills and to become incredibly wealthy by means of their passion is a dream that can happen in America.

Baseball is America’s sport through and through. Grab a beer, a bag of Cracker Jacks and enjoy the game.